Beechcraft upped Citroën for innovation in 1946

At the end of WWII the Beech Aircraft Company in Wichita, Kansas found themselves with a huge loss of Military aircraft orders and realized that what Americans wanted were cars.

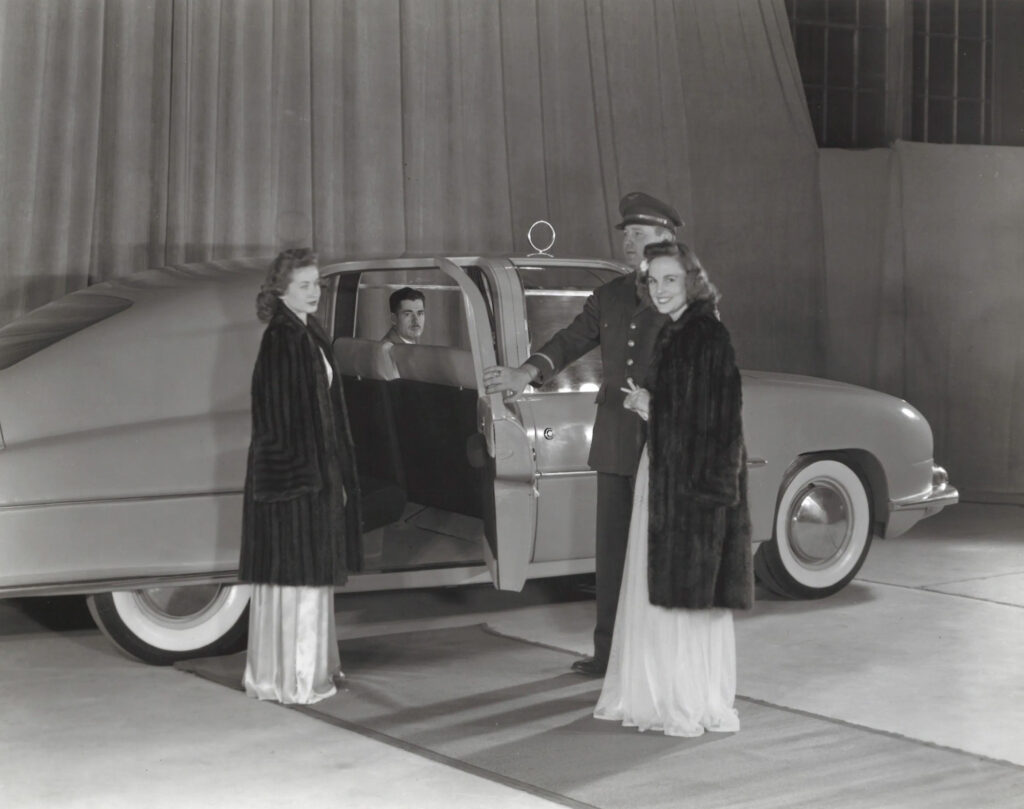

In 1946 they produced a concept car called the Beechcraft Plainsman (clever name – a “plane” inference) that applied aviation engineering to what they thought a road vehicle should be.

Far from plain and way before Toyota introduced hybrid technology, Cadillac and Mercedes Benz with air suspension or the industry changing innovations of Tesla, the Plainsman was so radically advanced even Citroën engineers must have marveled at the achievement.

The Plainsman was fitted with an air-cooled four-cylinder engine driving a generator, which in turn powered four electric motors, one for each wheel. It was fitted with fully independent air suspension. It also had an aluminum body, weighed just 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg), had a top speed of 160 miles per hour (260 km/h), and could carry six passengers.

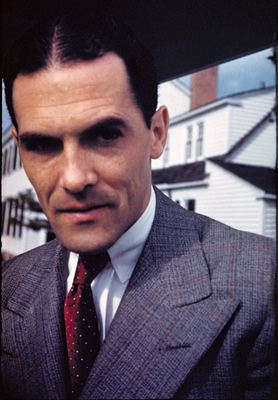

Much of the fascinating engineering of the car was done by a very eccentric Swiss engineer named Walter Otto Wyss.

You can read more about Wyss in this description for a documentary movie made about him; https://www.flyinghomemovie.ch/en/film-info/index.html.

Looking closer at the Plainsman’s technology, it was a gas/electric hybrid utilizing a 100 horsepower rear mounted air-cooled flat-four engine from Franklin motors similar to what Beechcraft was used to putting in it’s planes. (The car was designed to the engine could have be mounted in front as well but for the concept car, the rear placement was specified.) The engine drove a generator which powered four electric motors – one at each wheel. When braking the motors reversed polarity to slow the wheels down. Sort of like regenerative braking but unlike modern hybrids and EVs today, there was no on-board battery storage that would in turn feed power back to the electric motors.

The car featured the forerunner of electronic traction control as each of the four motors were designed to receive power based on which wheels had better grip.

The basic drivetrain tech was adapted from diesel-electric locomotives, and that basic tech also allowed the Plainsman to automatically find the most economic level of operation for the gas engine. And there was even a gauge to provide instant MPG information. It also allowed for an early form of cruise control, seemingly by setting the engine to produce a specific wattage from the generator.

Beechcraft claimed that the Plainsman could get up to 30 MPG at a steady 60 mph, and hit a top speed of up to 160 mph. With electric motor torque available from a dead stop, it probably had amazing acceleration.

Ahead of Citroën introducing hydropneumatic suspension in the DS, the Plainsman had an adjustable air-shock suspension system with driver-configurable ride heights thanks to an aircraft-landing-gear-derived setup.

Aviation practices went into the body to make it as advanced as the drivetrain. It was mostly aluminum, keeping the car’s weight to around 2200 pounds. A bubble canopy windshield, and side windows bent up into the roof also echoed aircraft design. It had a flat floor, and relied on hoops in the B and C pillars for strength.

As in an aircraft, the Plainsman was to come standard with a two-way radio telephone, the advanced feature to phones in cars readily identifiable by the ring-shape antenna on the roof.

Sadly it was too advanced for post-war America. Ford, GM and Chrysler were ramping up and cranking out cars for the masses. All this innovation came at price. While convinced they had a superior luxury car, they finally figured out the actual production price would be $15,000 US — far exceeding their initial target of $5,000 which was already more than twice the price of other North American luxury car offerings. And so, by 1949, the project was abandoned.

A pair of drivetrain mules and one un-engined styling mockup is all we have left to marvel at and wonder about what could have been.

They knew that, as an aircraft company, their best best to compete against the big companies used to mass-producing cars would be to make something rational, innovative, premium, and unique. They sure as hell managed that, even if it proved to be more expensive than made sense (over their $5000 target price, which was already like two Caddys) and the project was eventually abandoned.

No one seems to know what happened to the single prototype as all that remains are a these photographs.

If it did manage to survive, what a candidate it would be for the Lane Motor Museum in Nashville!

[Ed note: The Franklin Engine company was bought by the Tucker Corporation a year later to make engines for the Tucker 48. Franklin Engines are now owned by the government of Poland].

brillant.