How Citroën’s Brake Systems Ran Afoul With North American Regulators

By Chris Dubuque….

THE RULES

The first organized attempt of the US government to regulate car design happened in 1966 when president Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. This act ultimately created the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and resulted in a set of design standards called the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS). Virtually all of the original FMVSS’s became effective on January 01, 1968.

Before the FMVSS’s were mandated, there was an uncoordinated patchwork of state laws and industry recommendations in place for automotive design and safety. Many of the FMVSS’s specified design practices created earlier by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) or other non-governmental organizations.

Canada had a similar progression of regulations. The most significant change to Canadian laws happened in 1971 when Canada adopted automotive safety rules similar (but not identical) to the US rules. Canadian rules were called, Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (CMVSS), a name and acronym very similar to the US version. Before the CMVSS’s were adopted, early Canadian rules were like the early US rules; sporadic across the various Provinces and not organized into one agency.

SPLIT-CIRCUIT BRAKE SYSTEMS

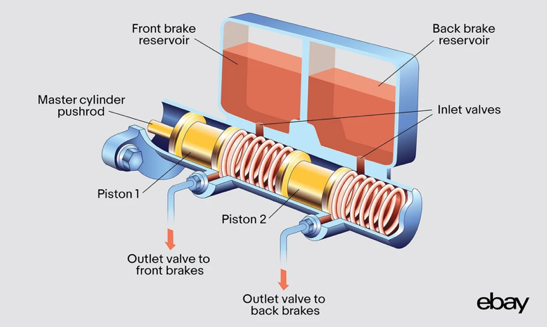

Starting in 1968 with the first FMVSS’s, USA safety regulators started imposing regulations on automotive braking systems. The specific rule for brakes was FMVSS Number 105. Among other things, this safety standard imposed a split braking system whereby one circuit was for the front brakes and a second circuit was for the rear brakes (although a diagonal split consisting of one front brake and the diagonally opposed rear brake was also allowed). This type of system is normally achieved with a dual-circuit brake master cylinder.

With this split system, a single failure of a tube or a seal somewhere in the car would only render two of the brakes inoperative. As an example, if a hydraulic tube to the rear brakes rusted through and spilled all of the fluid for the rear brakes, a dual-circuit master cylinder would allow the front brakes to remain fully operational, indefinitely.

FMVSS 105 goes on to require that if either one of these circuits fail, a light must illuminate on the dashboard to alert the driver of a problem. Keep this dashboard light requirement in mind as we will come back to it….

CITROEN’S BRAKE SYSTEM

The brake system on a DS does not have anything close to the dual-circuit master cylinder as envisioned by the authors of FMVSS 105. Nevertheless, it seems that Citroën was initially able to argue that the DS’s fully-powered brake system had a sufficient architectural split between the front and rear brakes such that the NHTSA accepted the existing DS brake system for the 1968 model year. Their full acceptance didn’t last long however.

DASHBOARD INDICATION

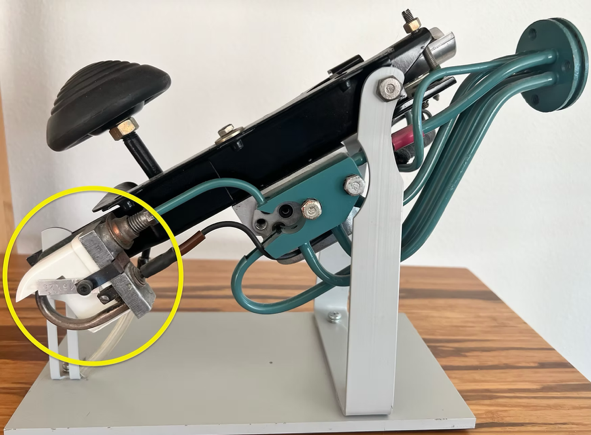

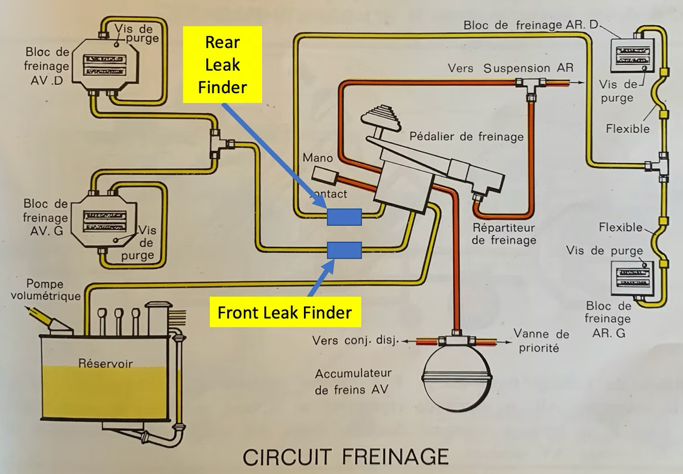

There was one aspect of FMVSS 105 that Citroën clearly did not meet on 1968 models – it was the requirement that a light illuminate on the dash if either the front brake hydraulic system or the rear brake hydraulic system had a fault. DS’s of the era only had a single pressure switch in the entire hydraulic system. This switch was mounted on the brake pedal assembly and measured source pressure available for the FRONT brakes.

But what about source pressure available to the rear brakes? The rear brakes on a DS are fed from the car’s rear suspension, but without a dedicated pressure switch. As a result, the DS was not in compliance with FMVSS 105.

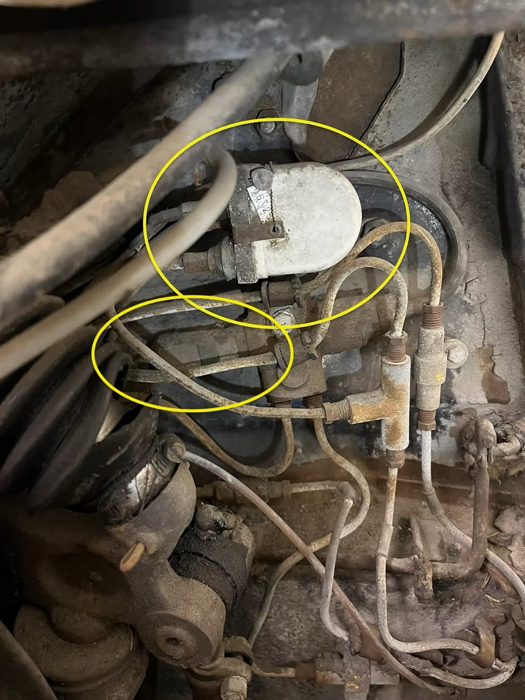

Somehow, Citroën was able to deliver 1968 models in the US with the existing indication system (probably by receiving a waiver). On 1969 DS’s, Citroën finally complied with the rule and added a second pressure switch, just for USA models. The pressure switch on the brake pedal assembly was re-purposed on USA cars in 1969 to measure the pressure source for the REAR brakes instead of for the FRONT brakes. At the same time, they added a second pressure switch that was screwed into the priority valve, thus providing a dashboard indication if the pressure source for the FRONT brakes was low.

With the addition of this second pressure switch, the system now had a dashboard indication if either the front or rear brake system supply pressure was low. Therefore, Citroën could now claim compliance with FMVSS 105.

ID19’s in the USA also received a second pressure switch in 1969 to comply with the rule, although due to configuration differences between a DS and an ID, the solution looked a bit different.

The additional pressure switches appeased the NHTSA for 1969 and 1970. But there were more regulatory problems on the horizon for Citroën’s brake system….

BRAKE SYSTEM FAILURE MODES

Despite the temporary reprieve(s) that Citroën received in 1968, 1969, and 1970 with their brake system, there appeared to be an overarching concern within the NHTSA about Citroën’s brake system architecture that didn’t go away with the pressure switch changes discussed above. The concern was that a single leak anywhere in brake system would eventually drain the entire hydraulic system, and therefore the car would eventually lose all braking.

To respond to the NHTSA’s concern, Citroën incorporated new devices in the brake system on all North American DS’s in April of 1971 that would contort the car’s brake system failure modes into a behaviour more like that of a dual-circuit master cylinder. These devices were called, Leak Finders.

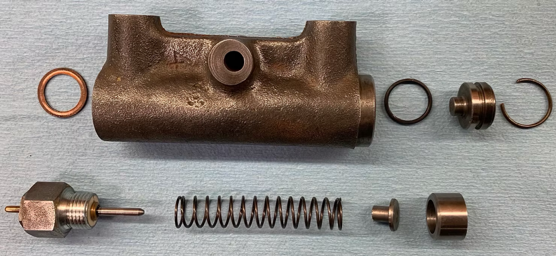

LEAK FINDERS

Leak Finders were small hydraulic components that were located in the tubing leading to the front and rear brakes. If there was a hydraulic leak somewhere downstream in the brake system, the Leak Finders would shut off flow to the affected brake pair, thus retaining hydraulic system integrity for the remaining two brakes (as well as for other hydraulic systems on the car). If a Leak Finder detected a leak and shut off flow, a mechanical switch at the end of the Leak Finder would be actuated to illuminate the red STOP warning light on the dashboard.

In industrial and aviation circles, this type of device is called a volumetric hydraulic fuse, since it passes a specific volume of fluid before it “fuses” and shuts off flow. The fluid volume needed to “set” the fuse is designed to be somewhat more than the normal volume of fluid needed to apply the brakes. In this manner, the fuse will never “set” with normal braking activity, but will “set” if an abnormally high volume of fluid passes out to a set of brakes.

Leak Finders were installed on all North American SM’s and on all North American DS’s starting in April of 1971.

Two Leak Finders means two switches – one switch for the front brakes and one for the rear brakes. As such, Citroën was again able to claim compliance with the dashboard indication requirement of FMVSS 105. Note that once the Leak Finders were incorporated, Citroën no longer needed the “second” pressure switch that was incorporated on US model DS’s in 1969 and so they deleted the one that was mounted on the brake pedal assembly. This left only one system-level pressure switch, installed on the priority valve (DS’s) or on the security valve (ID’s).

CONTROVERSIES WITH LEAK FINDERS

Leak Finders were specifically designed to address the NHTSA’s concern that a fluid leak in the brake system would eventually drain the entire hydraulic system and leave the car with no brakes at all. Leak Finders solved that. However, in what seems to be a case of extreme tunnel vision on the part of the NHTSA, a leak elsewhere in the hydraulic system on a DS still could drain the entire hydraulic system and still leave the car with no brakes. It seems to me that the NHTSA won the battle, but lost the war on this one.

Furthermore, Leak Finders made bleeding the brakes quite a chore since the Leak Finders interpreted brake bleeding as a leak and therefore shut off flow to that set of brakes before you could purge the air. The key to bleeding the brakes is to press on the pedal exceedingly lightly, which allows a very small flow around the outside diameter of the Leak Finder piston, which prevents the Leak Finder from closing off flow.

There is a school of thought (and in my opinion, a valid one) that Leak Finders do more harm than good. Any air that gets into the system, whether due to poor brake bleeding or from something else, causes the leak finder(s) to completely shut off flow to their respective brakes, leading to significantly reduced stopping capability. On a European model DS, air in the brake system causes a disconcerting delay, but full braking will be ultimately be available.

OTHER BRAKE SYSTEM CHANGES ON NORTH AMERICAN CARS

Besides the pressure switches and Leak Finders, Citroën made other changes on DS’s and SM’s to comply with North American brake system regulations:

- DS’s and SM’s in the USA were equipped with unique brake pads and brake shoes starting in the late 1960’s. Despite quite a bit of research, it is unclear to me what was different about these parts, but most likely, the lining material was specially formulated to comply with stopping performance requirements of FMVSS 105.

- North American DS’s from 1971, and all North American SM’s, had unique brake rotors and brake drums. The steel alloy in the brake rotors seems to have been different, likely due to stopping performance requirements of FMVSS 105. Also, both the rotors and drums on North American cars were marked with wear/re-grind limits. These numbers were in the units of inches and were painted onto their periphery. Since these numbers were just only painted or stenciled on, it is rare that they are still visible.

- North American DS’s after 1971 and all North American SM’s had certain hydraulic tubes in the brake system coated with a white Nylon material called Rilsan for added corrosion protection. I am assuming that this was part of a deal that Citroën swung with the NHTSA to help avert the general discomfort that the NHTSA appeared to have with the overall brake system architecture.

ULTIMATELY, WAS THE NHTSA SATISFIED?

While researching this topic, I discovered a series of letters between Citroën and the NHTSA that were buried on the NHTSA’s website. These letters, dating from around 1974, discuss the problem that the NHTSA seemed to have right from the start – that a fluid leak in the Citroën brake system would eventually cause the car to lose all braking. In one of these letters, the NHTSA appears to have been leaning toward forcing Citroën to implement a standard dual-circuit master cylinder on any new cars to be homologated in the USA. By this time, Canada had (nearly) identical rules, so this issue would have applied to all of North America.

This threat of forcing Citroën to use a conventional master cylinder happened after Citroën had stopped selling the DS and SM in the USA, so it would have potentially applied to the GS or CX, both of which Citroën had been considering for importation. Converting a GS or CX to have a conventional master cylinder would have been a major redesign, putting yet another nail in the coffin of the idea of importing either model.

More research on this topic revealed a surprise. It turns out that Citroën finally was able to score a win with the NHTSA and by the end of 1975, the Feds agreed to revise FMVSS 105 to accommodate a fully-powered brake system with an accumulator back-up. Specifically, if a car so-equipped was able to make 10 stops from 60 mph on the brake accumulator and still meet certain stopping distance requirements, the Citroën brake system would be allowed.

But it was too late. Citroën had given up on North America by then, for this and many other reasons. It was only about 24 months after the NHTSA caved on the brake system issues when Citroën’s American Subsidiary, Citroën Cars Corporation, officially ceased operation in the USA.

Even though FMVSS 105 and CMVSS 105 have been revised several times since the 1970’s, the wording about Citroën’s brake system is still there today, 50 years later.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Personally, I am very comfortable with the original brake system design on DS’s and SM’s, especially after LHM came into the picture. In my own experience, conventional master cylinders using brake fluid on 1960’s and 1970’s cars were much less reliable than Citroën’s system. I am also not a fan of the Leak Finders, since even a little air in brake system (a relatively common occurrence) can lead to a significant reduction of braking capability.

Yet, I can also see the NHTSA’s side of the story. You have pretty much the entire world going down one path and then along comes Citroën with a very unusual braking system that, at least on paper, has some architectural weaknesses that a dual-circuit master cylinder doesn’t have. After all, the DS has a brake system that was designed 75 years ago, well before the dual-circuit master cylinder was invented by the Wagner company.

Paul Mages, the genius father of Citroën’s hydraulic systems, fully understood the plusses and minuses of his own design. From an old 1980’s interview, he had the following to say about his first testing of fully-powered brakes in the 1940’s, using a Traction Avant as a test-bed:

“…I then mounted the same device ..… on an 11CV Traction Avant. It is obvious that to use brakes of this kind is quite revolutionary in the industry and it entailed risks that I had trouble accepting. I personally drove a very long time with the car so equipped, but I drove alone, trying to only put myself in difficult situations. I never had a problem. But I said to myself, there may be a day – it’s possible that something will fail and like all technicians, I had doubts. But at the same time, I also said to myself, why wait? If my brakes were installed in production, it would surely save human lives! We therefore put several cars in tests, first at the design office. I started by putting one of my collaborators on the road, but in the evening, I waited for him. I did not leave before his return and I can tell you that I was very worried until he came home. Subsequently, other cars belonging to the central laboratory were also put on the road. There were four of them that rolled around, including on the Montlhéry road circuit. I have never been happier than the day when a test driver (M. Tudoux) came to see me at the design office to say that my brake system had saved the lives of two kids. He was coming back from doing tests and two kids appeared in front of his car; their lives saved by the very rapid reaction of my brakes….”

Very helpful, nicely explained. Well documented

Chris,

Gosh, i had no idea that all of this went down.

Kudos to you for pulling all of this history long and involved together not to mention explaining it clearly as well.

For the few cars sold here annually in N. America, it is surprising that the company made the effort. That said, one does not know if the expense was covered by the number of cars sold.

Thank you for your grand effort. And explanation.

Bill Blaufuss

Excellent and very interesting, indeed, especially for someone like myself who did not “grow up” in North America!

The US was not the only country that was not “happy” with the system, as Swiss DSes also had the leak finders (not sure after what year) – Switzerland also required dual circuit brakes on all A-models in the early 70ies (again, not sure after what year, but definitely between 1970 and 1976).

Just putting the final touches on my US model 1970 Mehari, I can attest to the effort Citroen made to sell their cars in the US: apart from the obvious changes to the front with bigger headlights (that, unfortunately, cannot be adjusted to load anymore as on European models), 2-speed wipers, electric windshield washer, reversing lights, hazards lights! All this must have cost a fortune for a small number of cars!

Til

What about the issue of adjustable suspension height? I thought Citroëns were banned for that reason!

Hi Morel,

The bumper height and bumper strength rules have been widely reported to be the reason why Citroën left the North American Market. I think this is true. But there were a variety of other reasons that were piling up on Citroën as well. The brake issue discussed above was perhaps one. Richard Bonfond (the best authority on Citroën North America), reports that in addition to the technical challenges with the new FMVSS/CMVSS rules, Citroën was in a financial crisis at home, and Peugeot, now in control of Citroën’s fate, had little interest in having Citroën continue on in North America. Richard Bonfond has a great book that discusses Citroën in North America, called, “What a Ride, Growing up with Citroën in North America.” I suggest finding a copy if you are interested in this topic.

One thing I noticed on your picture of the brake valve: the pressure switch has a white housing, rather than the black housing of mine – I only came across one pressure switch with white housing so far, and it had a much lower pressure calibration (stamped 15/25, I assume kg/cm2), than the one with the black housing and WAS connected to the rear suspension (I remember because I could not figure out why) – so after reading your article I now assume that this was a US model brake valve and so it seems like US spec DSes were different, even before the leak sensors appeared.

Best – Til

Chris another great article Bravo

Leak finders were a plague…. The slightest air in the system caused a delay in the braking, anywhere from a fraction of a second to much longer. The driver’s instinctive response was to press harder having the effect of slamming on the brakes, usually locking the wheels or at minimum causing a big upset to passengers and traffic. The idiot light, true to its name would shine brightly beseeching driver who within this delay, couldn’t stop to STOP!….. SLAM!

Air got pulled into the system if the resevoir filter was dirty, fluid was wrong or if a sphere diaphragm failed allowing nitrogen to dribble or surge through. Occasionally a sphere would suddenly blow and not just froth all the fluid in the resevoir but blow the green can up like a balloon. An hydraulic system didn’t work well with a gallon or so of bright green (or grey-brown) blancmange. If the filter were sluggish it could be obstructed with black “chewing gum”, the gooey leftovers of badly deteriorated sphere diaphragm(s). (This deterioration was never seen in red fluid cars unless LHS had been contaminated with oil or tranny fluid.) An hydraulic pump could send air to the brakes by sucking air past the brass ring seal if the filter was dirty. A worn seal was prone to suck. Sometimes the brass ring would adhere to the adjoining surface and spin the ring. This would wear out the o-ring in it’s groove, thus failure of the seal. I used to replace the brass ring with a modern double lip rotation seal and add a second double lip seal externally behind the drive pulley. I would dynamically test every pump under vacuum after rebuilding. The cars before leak finders seemed much safer. After shutting off the engine at speed on a test run you could reliably stop the car over and over again so many times I’d lose count.

I meant to say “apply the brakes repeatedly on a long downhill with the engine off”.

Tres bon article.

Merci Chris

I remain a fan of Front Wheel Drive, which is common today, but once was very rare. I drove (and maintained) my brake fluid 1961 Citroen ID-19 for many years!

LHM was so much better!

I discovered that castor oil could help the brake system as a conditioner, but I had to buy it from the pharmacy. The pharmacist would always give me a funny look, but I didn’t care to explain– it was for my car.

The ID-19 had a Parking Brake that worked on the front inboard disc brakes. American cars had parking brakes acting on the rear. The hidden danger of “Emergency Brakes”– if they locked up the rear wheels during a panic stop, then a true emergency occurred –because the car might do a 180 degree spin. This odd situation led to the safety requirement of a proportioning valve in the brake circuit to the rear, so that if ever a driver had to lock up the brakes, the front brakes would lock up first.

This was, of course, before the advent of anti-lock brake systems. Sometimes during the job of bleeding the brakes, the proportioning valve would shut off the hydraulic pressure and leave air in the system, unless the job was done with the wheel resting on the ground.

Certainly a couple of badly considered engineering changes. ‘Leak finders’ being the most obvious wrong idea. However, many cars had either under-designed or awkward systems: I remember Rolls Royce having a basically horrible multiple system, also involving special fluid (castor oil again, in tribute to WWI aircraft engines no doubt). Split systems in other cars were sometimes fed from a single, remote reservoir, proportioning valves could also cause maintenance issues, and today, we have ABS systems that are both complex and expensive to repair. I was surprised a few years ago when a rear line leak in my Ford truck convinced the ABS to shut off the front brakes too…