Citroën. 100 years of the Eiffel Tower illumination

In 1925, André Citroën collaborated with Fernand Jacopozzi to illuminate the Eiffel Tower in the name of the chevron brand. A historic publicity stunt by the former, a technical feat by the latter, we celebrate 100 years of the manufacturer’s famous Paris landmark advertising.

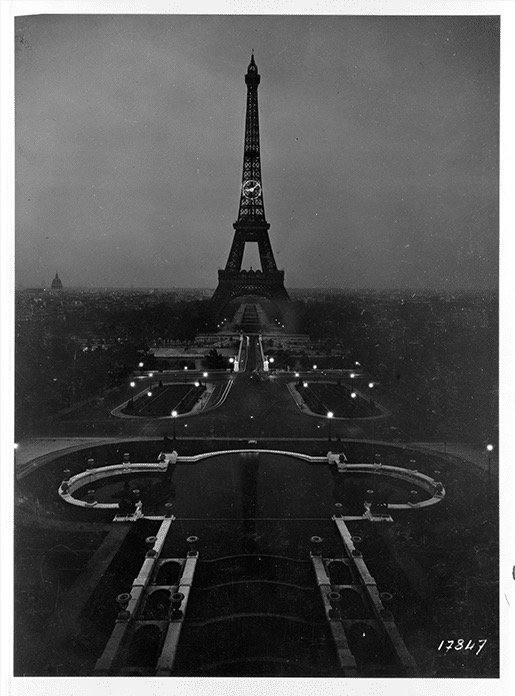

The Eiffel Tower has been a symbol of illumination and brilliance since its debut in 1889 for the International Exposition. The tower was adorned with 10,000 gaslights lining the trusses and platforms in its early days. By the time the 1900 Universal Exhibition was held, the tower’s illumination had transitioned to electric lights.

A giant, 20-foot illuminated clock installed above the second floor showed the time from 1907 on.

Renault refuses, Citroën accepts

In early 1925, as the great Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts was announced in Paris, to run from April to October, Gabriel Thomas, then chairman of the board of directors of the Eiffel Tower, had a brilliant idea to put the monument in the spotlight with illuminated advertising. Thomas contacted Fernando “Fernand” Jacopozzi, an entrepreneur and decorator specializing in illuminations, who had made a name for himself by lighting department stores, the Arc de Triomphe and even Notre-Dame de Paris. The Italian, based in the City of Lights, took up the challenge, but he needed a sponsor to finance this colossal operation. Following the refusals of the Magasins du Louvre and Renault, who found the project too expensive, he turned to André Citroën.

The two men had met during the First World War. Like other industrialists they were brought together by the government and assigned tasks for the war effort. Citroën, despite his search for innovation in advertising (he had flown the first promotional plane in 1922), refused the tower illumination proposal at first, but with further consideration of the marketing opportunity, soon changed his mind. Construction began in May.

An extraordinary project

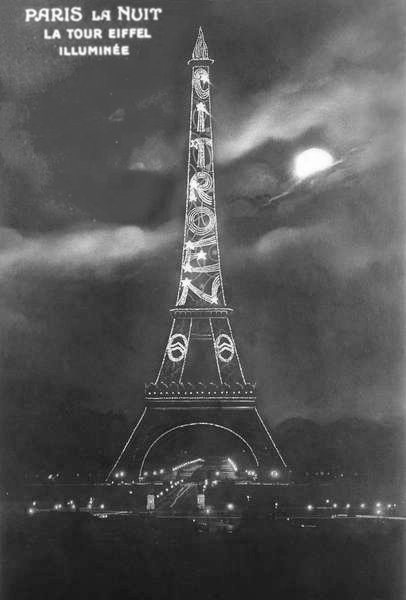

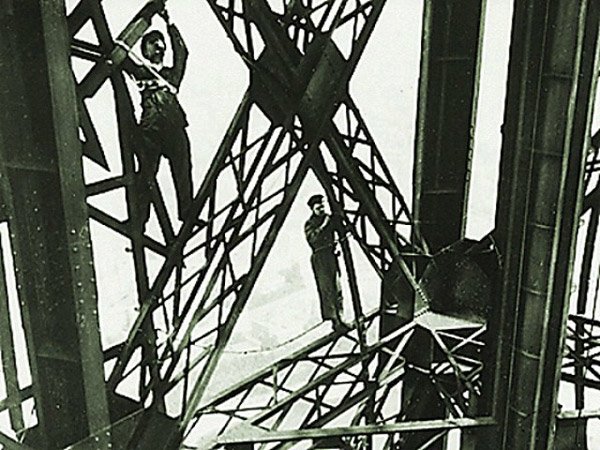

More than 200,000 Philips bulbs, 100 km of cable and a 1,200 kW power plant were installed. Superstitious, Jacopozzi feared the number 13 and refused to have more than a dozen workers on the job site simultaneously.

The first lighting took place on July 4, 1925. The name Citroën, written in glowing letters each thirty meters high, sparkled in the Paris sky, above two logos of its brand. It was recorded in the Guinness World Records book as the world’s largest advertising sign. Only the side overlooking the Trocadéro was lit at first. The lighting of the Bourdonnais side followed two weeks later, then the Suffren side another fortnight later. The fourth side remained in the shadows to avoid light interference that would have made the patterns illegible.

There were nine motifs in total. In addition to the name Citroën, operators could make stars, arabesques or even the silhouette of the tower appear. They could even create animations! This feat put Citroën and Jacopozzi very much in the spotlight. In 1926, 175,000 light bulbs were added to create a fountain on the Trocadéro side for the Paris Motor Show.

The tower’s illumination was attributed to the successful completion of the first transatlantic flight in 1927 by Charles Lindbergh in the “Spirit St. Louis”. Having seen the Citroën lights of the Eiffel Tower acting as a beacon, he flew toward it and after circling the Eiffel Tower, turned northeast for Le Bourget Airfield, landing at 10:22 PM local time, after 33 hours, 30 minutes in the air. As the roar of the Spirit of St. Louis‘ Wright Whirlwind engine died down, it was replaced by the roar of thousands of cheering Parisians.

André Citroën immediately invited Lindbergh to visit his Quai de Javel factory in Paris. At the end of the visit, a grand banquet was held there in his honor with 6,000 guests including all the factory workers!

André Citroën greeting Charles Lindbergh in Paris.

Between 1933 and 1934, a 50-foot diameter clock returned, telling the time using hands formed by beams of light. It was added to the Citroën lights, placed in the “E” of Citroën.

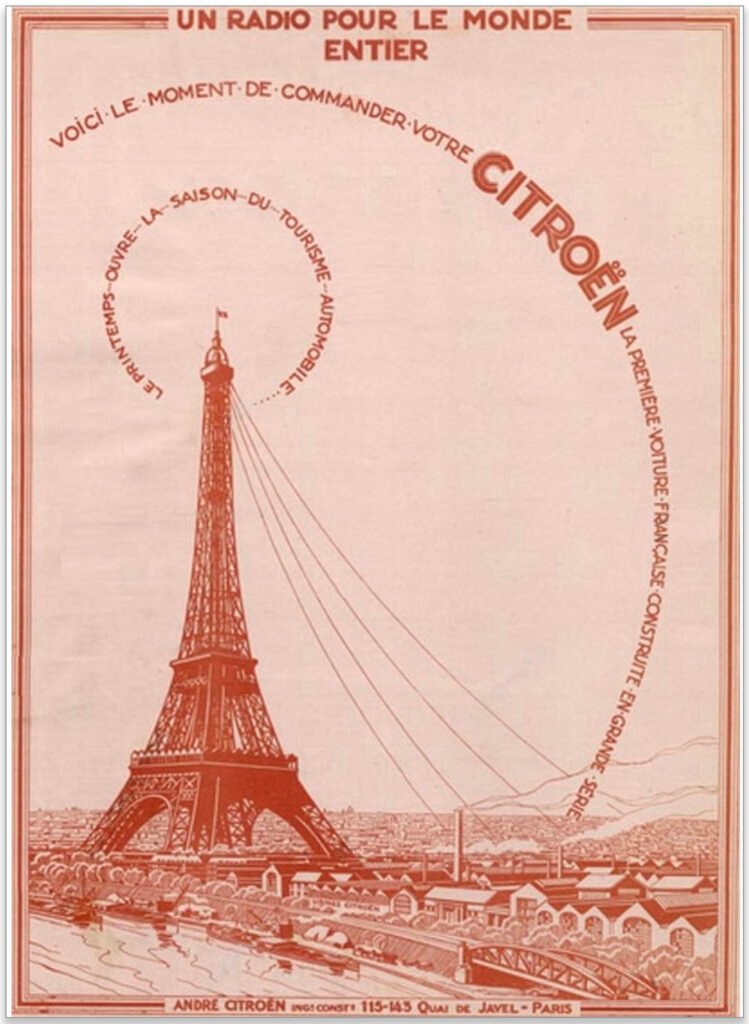

Citroën also ran ads in radio broadcasts from the Eiffel Tower.

André Citroën considered abandoning the costly illumination venture in 1927, but could not bring himself to have other brands replace his on the Eiffel Tower, whose administrators had then launched a call for tenders. He negotiated a new contract and kept the illuminations in his name non-stop until 1934, two years after Jacopozzi’s death. Even after André Citroën’s death on July 3, 1935, Citroën lighting was reactivated punctually until 1936.

Subsequently, Citroën organized several presentations at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, such as those of the BX and the second generation C3.

Today, the Citroën name has disappeared from the tower, but the sparkling that occurs every night can be attributed, in good part, to André Citroën and his visionary marketing commitment.

100 years on — July 4, 1925, to make the centenary of Citroen advertising, the Eiffel Tower will be lit up in grand style. Because technology has changed a lot in a century, it’s not yet known exactly what will be on the program. In addition to the illumination, an artistic performance is expected. The company has stated that it will also use the event to unveil its new Citroën C5 Aircross, the second generation of its family SUV.