by Dave Kaniewski – (courtesy of Citroenian and Andrew Peel)…

1. Introduction

It all started in 1997 after a visit to Donnington and Silverstone race circuits to watch the vintage car races which included the Aero Engine Car Club, the seed was planted and we (my youngest son Scott and I) had to have a vintage racer with an aeroplane engine. Fast forward to 2011 and having relocated to the Isle of Man we now had time to start a new project, having just completed a Citroen Light 15 it was time to choose the parts.

Bentley and Merlin? No far too expensive. So we kept looking on websites and found the French Leboncoin web site where bargains are in plentiful supply. After weeks of scrolling there it was, a 1928 Citroen AC4 in a farmer’s field last used as a pickup truck having the body cut off from the B post to the rear bumper. After negotiations through our chosen freight company (French speaking) the AC4 and spares were trailered and ferried to the Isle of Man.

We then searched for a suitable aero engine that wouldn’t overload the chassis, online searches and many phone calls later a contact was found (Dave Strange in the Bristol area). He restores vintage plane engines and had a de-Havilland Gipsy Major engine that he rebuilt for a customer who gave back word after crashing his Tigermoth. The price was agreed and shipping to the Isle of Man organized.

2. Strip and Paint

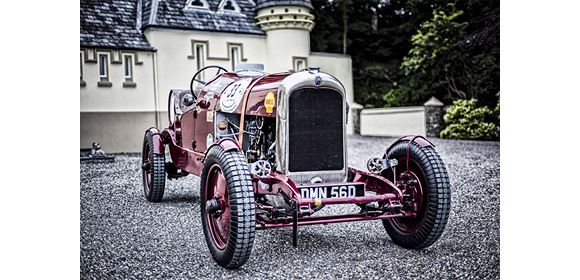

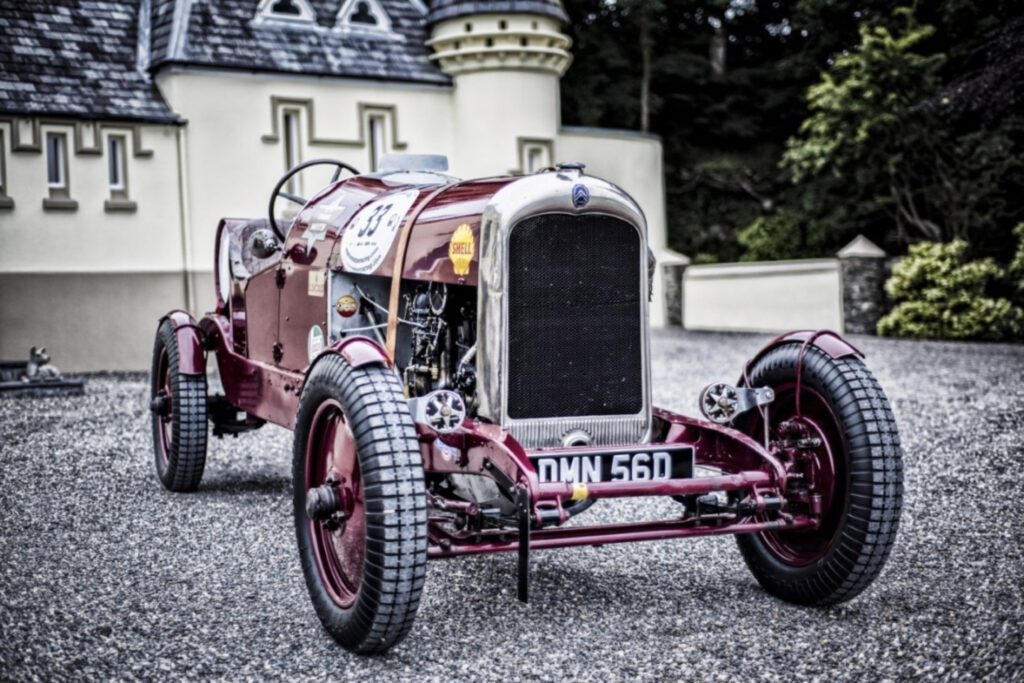

The AC4 was completely stripped to bare bones, cleaned, prepped and given a coat of crimson 2K paint. All mechanical issues were renewed or repaired; the front axle and steering box where repositioned to give right hand drive. We were impressed by the design of the chassis components and how everything converted to RHD. The springs where stripped and some leaves removed to allow for a much lighter car. The remaining body parts were placed in storage. A matching set of 4 wheels were obtained and fitted with new Blockley vintage pattern tires to give the period look.

3. Engine and gearbox

Once the engine arrived, the first task was to assess how to mount in the chassis as when the engine is in its intended airframe the engine runs with crank on top and cylinders below (This gives the pilot maximum view from the cockpit). We first looked at the idea of keeping the crank on top and a large drive chain from the propeller flange to the gearbox, which would be in a similar position to a normal motor car. However the torque of the unit was so that the drive chain and associated gearing would have had to been on an agricultural scale and custom made. So it was decided to flip the engine 180 and concern ourselves with lubrication distribution and carburetion.

The engine when in the aircraft uses a dry sump system and a geared engine driven pump to deliver oil to the main crank bearings and journals. Gravity then takes over and feeds camshaft and push rods then the oil ends in crankcase troughs which are then scavenged back to the main tank. The engine is designed to perform in any 360 plane but for a limited time, as the engine was now turned upside down to its original design, the top end of the engine would be starved of lubrication. A new oil rail had to be fitted to feed each individual rocker; the original magnum top crack cover was drilled and machined to incorporate a new sump as oil quantity was increased to successfully scavenge and to effect oil cooling. The original airframe oil tank had air cooling from cold propeller wash at high attitudes so oil cooling was never a concern on the original aircraft.

Electrics are very basic, consisting of twin magnetos and two spark plugs per cylinder, common on most piston driven aircrafts. Both systems are independent which give redundancy if any component on one side should fail. The original starting equipment was a member of the ground crew who would “Spin the prop”. This was overcome by installing a starter motor from a Mercedes Sprinter panel van, machined and housed in the original gearbox casing and used the old flywheel ring gear and pinon of the old AC4.

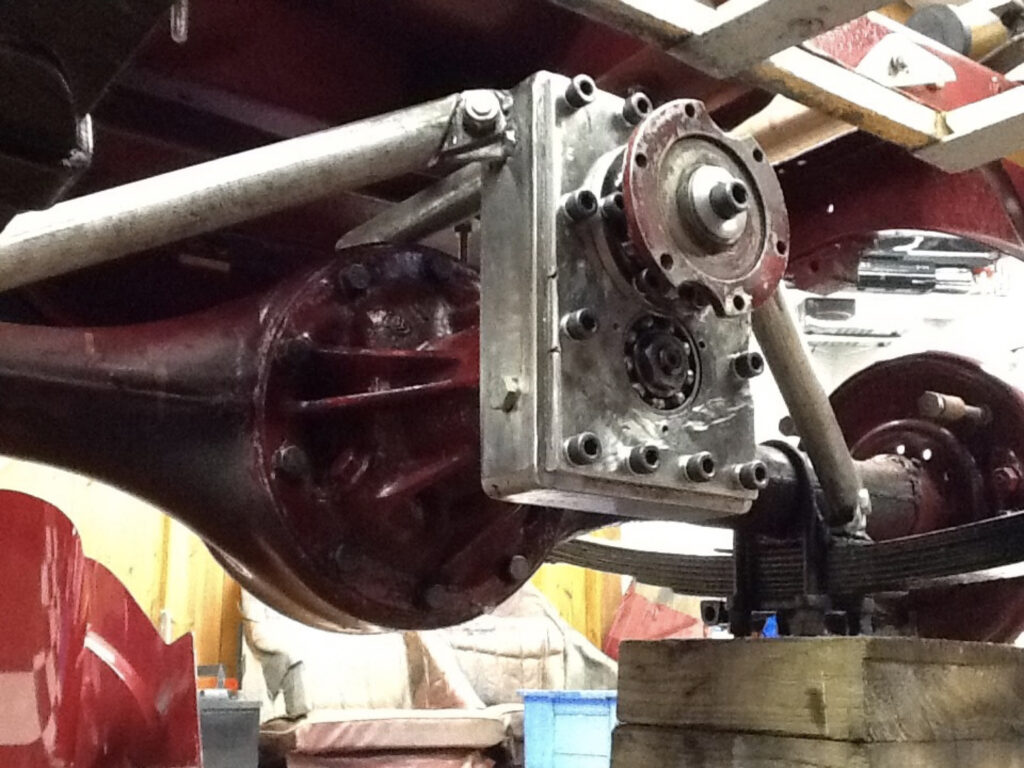

As above the gearbox and differential from the original car where very well made and quite substantial for an engine producing around 40HP, however the new engine rotates the opposite way to the original so the differential was spun and rotated 180 degrees so the piñon from the drive shaft ran on the other side of the sun gear, so in fact the gears mesh on opposites faces so it’s like having brand new gears.

The clutch of the original car was well worn and definitely not up to the task of transmitting all the power to the gear box and back wheels. The centre boss was machined from the original clutch and then mechanically fixed to a David Brown tractor clutch.

The biggest task was to marry the flywheel and Gearbox assembly to the prop shaft flange on the engine. The flange is attached to the end of the crank shaft by a long aluminium nut, you wouldn’t believe that this one nut would hold on a propeller and stay on when the airplane is on full power on a rapid climb but it did so that was retained and a shaft machined to accommodate the original nut assembly.

Then followed hours and hours of adjustment to true up to the flywheel. The first attempt ended up in sheering the machined shaft so dimensions where increased and more hours in “making true”.

To fit the engine and gearbox into the AC4 chassis we constructed a steel angle sub frame that incorporates the AC4 engine back plate the whole assembly then sits on modified brackets with 4 light commercial rubber engine mounts. As this assembly sits further back in the chassis a much shortened prop shaft connects gear box to the differential.

With modifications to the brake, clutch, throttle, steering shaft etc. A new driver’s position was created and we moved onto the next stage.

4. Bodywork

Well the plan was to recreate a typical Grand Prix race car of the 1920/30s. As in that era between the wars this involved selecting a car with a strong chassis, stripping the body off and finding a more powerful engine to fit, then construct a light weight body, this being the predecessor to formula one.

We started with mounting the AC4 radiator and grill on the chassis and then stood back, then with string and cardboard we played about finding the lines and proportions that looked like the race cars in found on the internet. Weeks and weeks later after cutting and bending alloy sheets (some ending in the bin) the body started to resemble a racer. We used the original fuel tank but encased it with a circular outer skin to get the look and increase safety. The original bulk head/firewall from the AC4 was used which gave a location for the steering wheel and dashboard. The positions of the seats were measured out and alloy tubs and squabs were made. Then we upholstered in old leather saved from the seats in the Light 15, a cracked and worn look worked perfectly.

The dashboard was cut and fitted with a selection of aero instruments and switches which were all mechanical. This saved on using the odd voltage of 28v used in many aircrafts.

We then stripped and painted all body parts with the paint used on the chassis as we preferred paint over polished alloy. Once the body was refitted we could now manufacture a straight through exhaust system, this involved making 4 short exhaust stubs to fit the 4 individual heads on the moth engine. These then connected to a 4in diameter header with slip tubes connecting all in stainless steel. We then TIG welded, preformed bends and straight tube all in 4in diameter out to the rear of the car.

Motorcycle mudguards were fastened to the brake back plates with thick walled stainless tubes made the vehicle road worthy but can be quickly removed for competition use, so a simple wiring system fitted (no lights or indicators) more-or- less, this completed the body styling.

5. Snagging and Fine Tuning

After cleaning out the AC4 radiator we used it as the engine oil reservoir with an electrical scavenging pump hoping the radiator would act as an oil cooler. However this was unsuccessful so a wet sump was made and fitted as previously mentioned.

This works well but sump level is very critical to avoid oiling plugs and smoking exhaust on overrun.

The starter pinion didn’t last long, the long compression stroke saw to that so we engineered a direct engine starter motor. We turned an adapter shaft that was bolted to the primary gear at the end of the crankshaft, a 5:1 reduction gearbox with two sprag bearings fitted and finally a modified sprinter starter motor does the job perfectly. Oh and a decompression system manufactured to help!

A 12v alternator was mounted on new brackets and driven via the engine output shaft. A simple wiring circuit was designed that included an electric cooling fan, horn, and battery isolator.

6. Test run and MOT

After a few short runs down the lanes, no niggles were noticed so we fitted a baffle in the end of the exhaust pipe just to take the bark off it and next it was time for the MOT.

On the Isle of Man vehicles are only tested once so it’s quite a stiff test, Pulling in to the test station yard an examiner came out to start the assessment which went well, but he declined the offer to drive it into the station and stood well back as l started the engine and drove in. Once directed over the car lift, 2 more of his colleges joined in smiling and scratching their heads but all in all they were happy tapping and asking questions. They could see that every nut and bolt had been removed, inspected and refitted to a good standard. Then it was on to the brake testing, after standing on the cable brakes it was clear figures didn’t add up but after consulting with each other the decision was made that as no comparison figures were available, they couldn’t fail it!

Happy days and we were on the road. It soon became apparent that because of a rev limit of 2400 rpm, the engine revved out at 65 mph, so we manufactured a step up gearbox to mount on the differential. A simple 2 gear setup with a 2:1 ratio giving a maximum speed of over 120 mph and a low rpm cruising speed.

7. Driving and competing

Well as many of you will know, vintage cars drive very different to modern ones, yes they are a handful add a massive torque delivery and I can best describe the experience as being in an out of control stage coach on a very narrow lane. Top gear speed is from 30 mph at 400 rpm, but if you floor the throttle and hold on to 2400rpm and it’s 122 mph if you dare! l bottle out at 80 mph on a good wide road (the TT course) but have gone the fastest on the runway at Jurby.

Handling wise, the steering is very direct but heavy. Suspension is lively with only friction dampers on the front axle, there is lots of roll at the rear causing oversteer when pushed and feels like the car wants to swoop ends.

On normal roads 30/50mph in top gear is just brilliant, engine and exhaust notes up and down the rev range is addictive. At this speed the engine stays nice and cool but traffic lights and town centres can quickly over heat the engine even with the fan on so stopping to cool off are part of the fun.

In competition here on the IOM is limited to the Manx Classic Three Hills event, First time we dropped a valve seat, Next time we won 1st in class on all three hills. The last time we came last against Longstones 3 litre Fraser Nash. We’ll have another go after Covid.

We have to find an alternative gearbox as the 2nd gear has sheared its teeth not surprisingly, and the eccentric bush in the steering box is worn, otherwise we are happy with the car and hopefully the government leaves us vintage car enthusiasts alone to keep the industry alive and thriving.

8. Further projects

As gluttons for punishment we decided to bid at auction on 1 of 6 Douglas horse trams built in 1896. One owner from new and in need of major restoration, we won tram no34 and as well as restoring it to near original condition we decided to convert it to be able to use it on normal roads.

This involved removing the tram wheels and mounting the tram on a Nissan cab star rolling chassis with a mid-engine Mercedes c180 engine and auto gearbox, plus fitting a forward control driving position, oh and seat belts to comply to road safety rules.

Two years later, we are on the road (2019) and enjoying attending shows, carnivals, weddings etc. We enjoy good relations with the Cunningham family (that own The Isle of Man Motor Museum in Jurby) which means that after the summer season we are able to exhibit Tram 34 in the museum over the winter period.

After we completed the tram I said absolutely no more projects, well one day whilst volunteering in the museums workshop a crashed Cessna 182 came in to be broken up, so I couldn’t resist making a cheeky bid for the fuselage minus engine/wings and tail. Bid accepted and it is now behind my garage waiting to get converted into a cocktail bar/boys toy, and that is most definitely that!