By Thomas Urban….

During what most Citroën enthusiasts often refer to as the “golden age” (namely, the Michelin era), the engineers and designers at Citroën’s design office were frequently given free rein to create models that, in many respects, were “UFOs on wheels.” This was especially true of its high-end models; the SM, the legendary DS, as well as its successor, the CX. The well-known (and often true) adage, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” largely explains the significantly longer lifespan enjoyed by the latter two flagship models of the Javel-based company compared to most of their rivals.

This longevity however, also had its downsides. Among other things, when the time came for Citroën’s engineers to seriously begin work on the successor, it quickly became clear that the task would not be easy by any means. This was perhaps even more true in certain respects, particularly in the case of the car tasked with succeeding the CX (a task only slightly less daunting than the CX’s role in succeeding the DS, or the DS’s role in replacing the equally legendary Traction Avant).

Since the creation of the “UFO-like DéeSse,” times had changed. With the introduction of both the GS and SM in 1970, as well as heavy investment into Wankel rotary engine development with Comotor (a joint effort between Citroën, NSU), financial viability was becoming critical. The oil crisis in 1973 sealed Citroën’s fate for a takeover by Peugeot, forcing the double chevron brand to severely tighten its belt. All the ambitious projects envisioned for the CX (a V8, as well as boxer and Wankel rotary engines) were quickly shelved. Fortunately, the GTI and Turbo versions were granted development to prove that the CX deserved its premium status, especially in the face of the German sedans that already dominated the market.

When the time came for all versions of the CX sedans to be discontinued in 1989 (The CX wagon versions continued until 1991) after fifteen years of faithful service, it goes without saying that its replacement was eagerly awaited by both the most ardent Citroën enthusiasts and the French public.

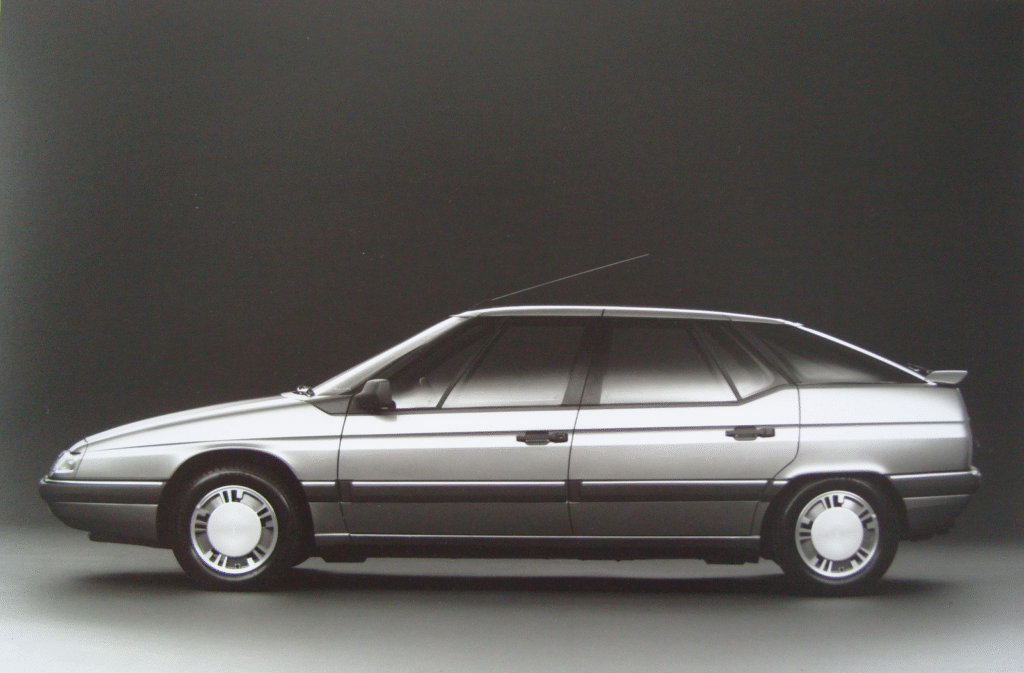

After extensive rivalry between Citroën in-house designers and external sourcing as to how the next-generation flagship should be styled, the XM bore the “DNA” of the double chevron brand as defined by the Italian coachbuilder Bertone. The XM possessed a refined visual lineage from Bertone’s design of the more compact Citroen BX introduced in 1982. (It was Bertone who would also go on to create the lines of the Xantia introduced in 1993). Noted at introduction for its aerodynamic design and innovative features, the XM marked a significant evolution in Citroën’s design. (Posterity has mostly remembered Bertone, though it should be noted that a Belgian, Marc Deschamps, was chief designer of the XM at Bertone).

Regarding the style of the newcomer, while not everyone appreciated it (as is often the case with Citroën models, you either love them or you hate them), it certainly left few people indifferent about it.

Just as the PSA Group was in the final stretch before unveiling its two new flagship models, the XM for Citroën and the 605 for Peugeot, it made a mistake that would largely torpedo their success; For the 1988 model year, its eternal national rival (Renault, to be precise) had just presented the face-lifted version of its own top-of-the-range model, the R25.

However, the executives at Citroën and Peugeot knew that this facelift was primarily intended to appease customers until the arrival of the R25’s replacement, the Safrane.

While the Safrane would ultimately not be launched until 1992, PSA’s management clearly feared that it would arrive sooner, and especially before the XM and 605 were finalized. The mistake in question was the decision to bring forward their launch by a year: while it was originally planned for sometime in 1990, it took place in the spring of 1989 for the XM and in the summer of that same year for the 605.

The consequence of this almost last-minute change of plans was an electrical and, above all, electronic system that quickly proved to be problematic, though in some respects, not much worse than the electrical systems of Italian cars from the 70s and 80s. The various electrical and electronic problems with the XM primarily affected models produced during the first two model years (1989 and 1990) and were largely resolved with the introduction of the 1991 XM.

Electrical issues, Bertone styling, and development under the control of Peugeot are the three main reasons that the vast majority of Citroën enthusiasts consider the CX to be the “last true Citroën.” It all depends, of course, on what one means by it, as this expression has been so overused, both by Citroën enthusiasts, the press and automotive historians. Moreover, it’s only partly true, because, in reality, the car that truly deserves this title is the Citroën Axel, also designed before the start of the PSA era but which wasn’t marketed until the early 1980s. (Produced in Ceausescu’s Romania, it was sold there under the name Oltcit and, in France, as the Citroën Axel). You can read more about the Axel and Oltcit in these articles in Citroenvie:

- Axel: https://citroenvie.com/citroen-and-oltcit-a-romanian-collaboration-leading-to-the-birth-of-axel/

- Oltcit: https://citroenvie.com/oltcit-its-not-a-3-door-visa/

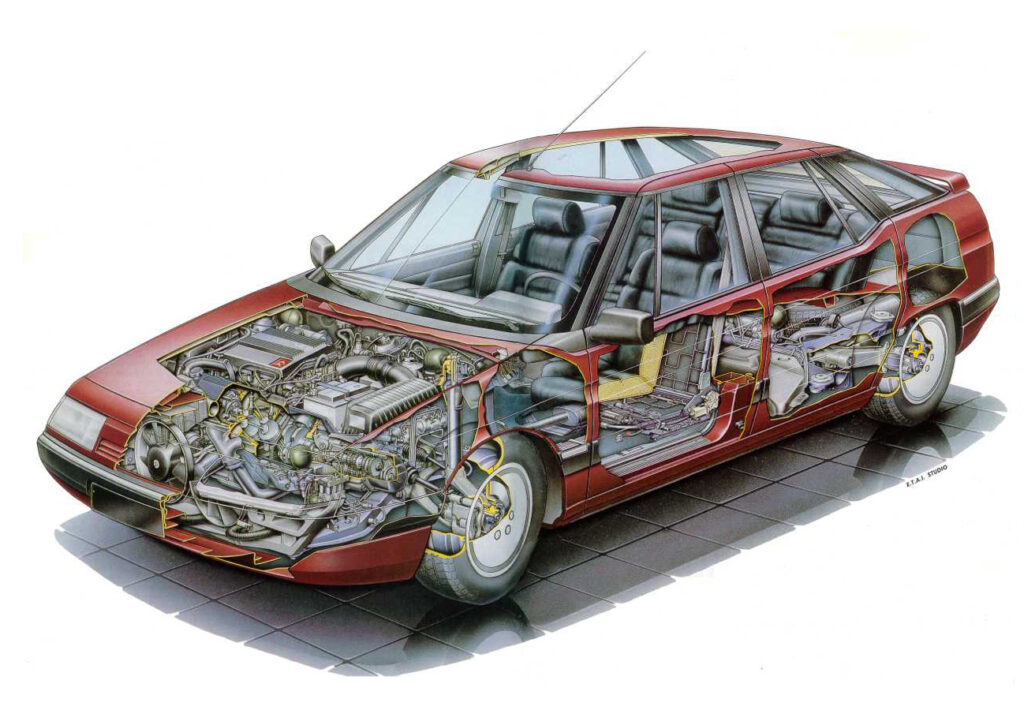

While neither the DS nor the CX before it had an easy task during their development and launch, they nevertheless proved to be remarkable. However, Citroën’s loss of independence, with its resulting consequences and constraints, inevitably added a significant further difficulty. One of the constraints was the need to share a number of common components, at least in terms of mechanical parts. Besides the underpinnings, the new large Citroën sedan would receive engines and transmissions virtually identical to those of its Peugeot cousin. It was clearly stated in the specifications for the XM from the outset that the CX’s replacement should be as “conventional” as possible.

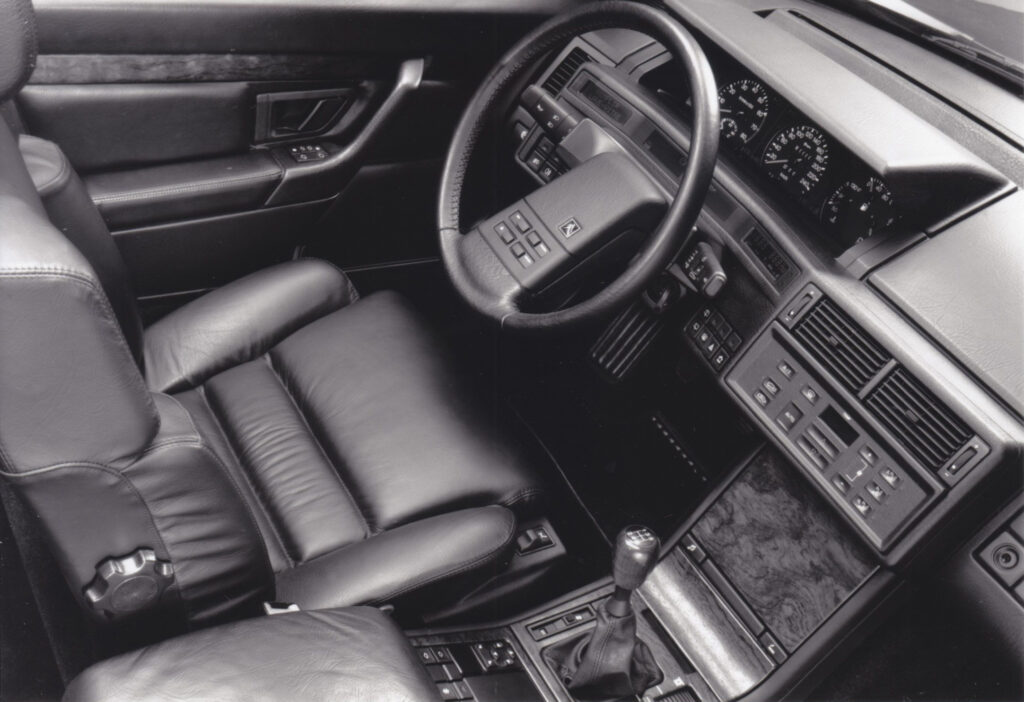

While this was ultimately not entirely the case (at least not as much as PSA executives had originally hoped), it must be acknowledged that, in certain respects, the new XM was less radical than its predecessor. The design team, for example, had to resign itself to abandoning the single-arm windshield wiper, the faired rear wheels, and the satellite type dashboard controls of the CX. All these signs clearly showed that (within the large sedan category, as in other segments), Citroën no longer had complete freedom of movement and would therefore have to accept conformity. This policy of “standardization” would continue for the XM even after its launch, as it would also have to abandon, in the summer of 1992, the single-spoke steering wheel (which had been a feature of almost all models of the double chevron brand since the launch of the DS in 1955).

There was, however, little risk (unless, of course, one suffers from a fairly advanced visual impairment) of mistaking the XM for a Peugeot 605. One might even suspect that some of the more penny-pinching executives at PSA would have considered it perfectly sufficient to simply offer a redesigned 605 with a facelifted front end and taillights as the CX’s replacement, thus minimizing development and production costs. (Who knows, perhaps some even openly suggested this idea to the then-CEO of the PSA Group, the “charismatic” Jacques Calvet).

Despite its Belgian-Italian (rather than French) origins, the XM retained a distinctly Citroën identity. This, along with road-holding qualities worthy of its illustrious predecessors, allowed it to boast of being among the benchmarks in its class, earning it the title of European Car of the Year in 1990 (an honour also bestowed upon the CX twenty-five years earlier). Unfortunately (and as mentioned above regarding electrical issues), the teething problems that plagued both the XM and its “cousin” (and rival), the 605, quickly damaged them both. Their image was tarnished, and their commercial success was almost irreparably hampered.

At its launch, the XM was only offered with two engine options: a 2-liter, 130 hp four-cylinder with fuel injection at the entry level, and, at the top of the range, the ubiquitous PRV V6 (Peugeot-Renault-Volvo, which first appeared in 1974 on the coupe and convertible versions of the Peugeot 504) in a twelve-valve version producing 170 hp. The introduction of this latter engine was a major event in the history of the double-chevron brand, as it marked (finally) the return to the Citroën lineup of a high-end sedan equipped with a six-cylinder engine (the last being the famous Traction 15 CV, whose production had ended in 1955, thirty-four years earlier).

Given its status as the flagship of the XM range, it was only offered in top-of-the-range trim level. One of its many standard features, included the renowned hydropneumatic suspension (renamed Hydractive, as it was now electronically controlled). The engine range gradually expanded from 1990 onward. A new four-cylinder engine, still with a displacement of 2 liters but now fed by a single carburetor (which explains its significantly lower power output of 115 hp), took over as the base engine as well as the first diesel option, a 2.1-liter with 83 hp. This engine was also be joined, during the 1990 model year, by another diesel option: a 2-liter turbo producing 110 horsepower.

Regarding transmissions, while all XMs came standard with a five-speed manual gearbox, a four-speed automatic was available with both the V6 and the 2-liter four-cylinder gasoline engine. The 1991 model year saw the XM benefit from a new, more refined and powerful version of the PRV V6, this time equipped with a 24-valve cylinder head, thus increasing power to 200 horsepower. The same year also saw the introduction of a new high-end trim level: the Exclusive. Standard equipment specific to this latest version included; Speedline branded aluminum wheels, leather upholstery (covering all the seats and rear bench seat as well as a larger surface area on the door panels), varnished wood trim on the latter as well as the dashboard and an automatic climate control system.

In 1992, the Turbo Diesel version also became available with an automatic transmission. All versions (regardless of engine or trim level) received new alloy wheels and a redesigned radio.

Like its predecessor, the XM was also offered as an estate (wagon vesrion), although it didn’t arrive until the end of 1992 (once production the CX estate models ceased at the end of the 1991 model year). Like the CX estate and other estate models in the Citroën range, it was produced on the assembly lines of coachbuilder Heuliez. Besides a rear overhang 25 cm longer than the saloon, the XM estate was also distinguished by its large, distinctive rectangular taillights.

From an engine standpoint, the range in the XM estate was considerably more limited than in the sedan. Gasoline engines included the 2-liter 130 hp fuel-injected unit and the 170 hp V6. Two diesel engines, naturally aspirated and turbocharged (2.1L with 83 hp and 2L with 110 hp), were also available.

Overall, only minor changes were made to the XM for the 1993 model year. The most notable was the discontinuation of the entry-level version with a carburetor. This system had become outdated and was disappearing from most French-made models. The 2L fuel-injected engine took over as the entry-level option. Catalytic converters on gasoline engine were gradually becoming more widespread around the same time (a consequence of new European emissions regulations). They resulted, however, in a significant drop in power, with the four-cylinder engine’s output falling from 130 to just 122 hp.

During the 1993 model year, a new engine also appeared in the catalog: the Turbo CT — a four-cylinder engine that retained its 2-liter displacement but whose power increased to 145 horsepower. At the end of that same year, the Hydractive suspension system was revised and improved, which, in the manufacturer’s eyes, justified its new name: Hydractive II.

Given how severe electrical problems on early XMs had damaged the image of the brand’s flagship model, Citroën deemed it necessary, even essential, to revise the entire model range for the 1994 model year. The other major change for this year was the introduction of a new self-steering rear axle (also found on the famous Xantia Activa version). Regarding trim levels, two limited editions were introduced: the Pallas and the Onyx, produced in runs of 1,500 and 2,000 units respectively. Regarding the engines, the displacement of the PRV V6 was slightly reduced, from 2,975 to 2,963 cc, although the power output remained unchanged. The CT four-cylinder engine, meanwhile, saw its power increased to 150 horsepower.

In 1994, the XM had already been on the market for five years. As is generally the case with most automotive models across all categories (from grand touring sedans to more mainstream models), it was time for a facelift, getting subtle external changes that included; a redesigned front and rear bumpers, as well as updates to the headlights.

Inside the cabin, the dashboard was redesigned, with a more modern look, abandoning the geometric lines, still strongly reminiscent of 1980s aesthetics, in favor of curves and softened angles more in keeping with current trends. The upholstery was redesigned, and regarding safety equipment (another concept that was becoming a key concern for both manufacturers and drivers), airbags were now standard equipment.

This “cosmetic surgery” was also accompanied by the introduction of the Hydractive II suspension system, improving ride quality and handling. There was also a renewal of the engine lineup, with two new four-cylinder engines, one gasoline and the other a turbodiesel. The former, equipped with a sixteen-valve cylinder head, had a displacement of 2 liters and produced 135 horsepower, while the latter was a 2.5-liter engine with 130 hp. A new limited edition, the Prestige (500 units produced), was added to the catalog.

With the 1996 model year, the XM was now equipped with a second front passenger airbag (standard on the higher-end versions and optional on the entry-level models). In terms of trim levels, the range saw the introduction of a new limited edition, the Harmonie (also limited to just 500 units). While diesel engines had always represented a significant (if not majority) share of production, from the 1997 model year onward, only the Turbo versions remained in the catalog.

At the top of the range, the “legendary” PRV V6, which powered almost all high-end models produced in France since the mid-1970s, both within the PSA Group and Renault ranges, was finally retired after nearly 25 years of faithful service. While its successor retained the same V6 architecture, it boasted a significantly more modern design. Like the most powerful version of the old PRV that equipped the XM (as well as the Peugeot 605), this new-generation V6 (internal code name: ES9) featured a 24-valve configuration. Though modern, it was not exactly a “powerhouse” (at least not in its original version), as its power output remained below the highly symbolic 200 horsepower mark (194 to be exact).

The arrival of this new top-of-the-range engine unfortunately meant that the XM lost another attribute typical of Citroëns from their “golden age”: the Diravi power steering.

Externally, apart from the monograms on the wings and tailgate, the only feature that allowed anyone to identify it was a model equipped with the ES9 V6 was the presence of a dual exhaust.

XMs produced from the 1998 model year onwards (all engines and trim levels included) gained a third brake light.

The 1999 model year saw the color of the turn signals change from orange to white, and, from a safety perspective, side airbags became standard equipment. Of all the limited editions offered for the XM (both in France and abroad), one of the most iconic is undoubtedly the last one, the Multimedia. Its name was quite fitting, as it boasted numerous multimedia features (now fairly common on most cars, but which, in the late 1990s, were still the preserve of high-end sedans). It was also the most exclusive in terms of production, with only 52 rolling off the assembly line.

The year 2000 marked the final production run for the XM, with production of the station wagon ending in February (marking, even though no one knew it at the time, the end of the line of “high-end” Citroën station wagons) and that of the sedan four months later.

At the very beginning of the 2000s, with the management of the PSA group having other priorities for Citroën as well as for Peugeot, it was five years after the disappearance of the XM that its replacement, the C6, was unveiled. Which, as everyone knows, experienced a commercial failure even deeper than that of its predecessor.

il y a une erreur sur la photo de la Safrane.

la Safrane de l’article est une Safrane 2, jamais vendu en Europe .