Robert Opron Retrospective – “TheTenderness of the Absolute”

By Stephan Joest, Amicale Robert Opron….

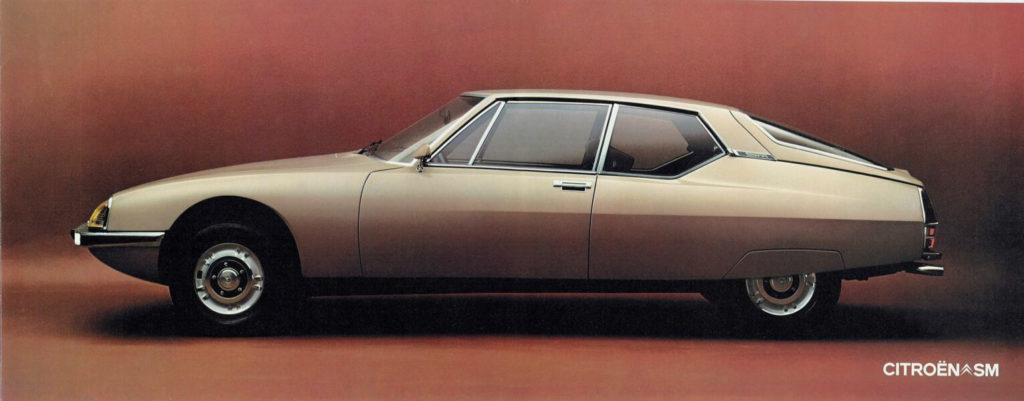

Anyone who delves into the history of the Citroën SM quickly finds themselves not only fascinated by one of the most elaborate feats of mechanical automotive engineering but also drawn to the vehicle’s design. This inevitably leads to the name of one of the greats of his time: Robert Opron.

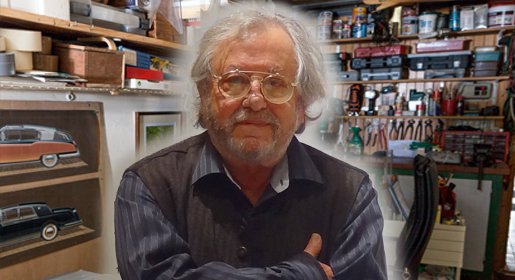

A few of us had the chance to meet the stylist in person, for instance, during the annual Retromobile event in Paris each February. This event traditionally brought together the “grandfathers and grandmothers” of Citroën history at the club stand, promising an extraordinary evening each time. Occasionally, Robert Opron would appear with his wife, Geneviève, usually engaged in conversation with contemporaries and friends.

The Oprons were also welcome guests in Germany – at various club meetings or at the Techno-Classica Essen, where, in 2012, they were honored as members of the Citroën SM Club Deutschland and the exhibitor association “Citroën-Straße” (“Citroën Street”).

However, Robert Opron was not a man of the grand stage and always avoided the spotlight. He accepted the German award only after I assured him that he would not have to stand on a podium or give a speech.

Ultimately, he received the certificate with joy and a bit of pride, having been overlooked for so long by the brand he always preferred above all others: Citroën. His wife, Geneviève, his childhood sweetheart whom he married in 1953, stood by him throughout his life, embodying the adage, “A man is only as good as the woman behind him.”

Walking through the exhibition with him, one would never guess that he had long retired. He continued to study forms, particularly models unfamiliar to him, including more modern vehicles. Looking back at his past work held little interest for him. When I attempted to photograph him in front of an exhibited SM Opéra, he became rather annoyed and waved it off—he wanted no association with a car he considered entirely disproportionate.

Back home, he would soon return to his desk, sketching new designs—always searching for the ideal form. His creative thinking was always evident in our discussions, often accompanied by a mischievous smile as he shared his distinctive opinions. “New and different thinking” was part of his philosophy, reflected in his famous sayings, one of which became the title of this exhibition: “The Tenderness of the Absolute.”

A deeper exploration of Robert Opron’s life work reveals an astounding diversity of designs over the years. He worked across multiple fields: designing aircraft cockpits for Northern Aviation’s Noratlas in his youth (he was also a licensed pilot), creating avant-garde kitchen furniture at Arthur Martin, working as an architect, and designing not only passenger cars but also transporters and trucks such as the Renault Magnum AE or microcars for Ligier. His mission was always to create something new, something never seen before. The book “L’Automobile et l’Art” by Peter Pijlman, a reference on Opron, lists over 70 vehicles he designed or was responsible for—not to mention countless unrealized sketches.

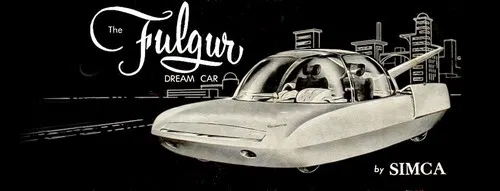

Perhaps his most revolutionary design was the Simca Fulgur, considering his concept studies. The story of this car alone is worth telling.

In the spring of 1958, the Belgian youth magazine Tintin (German: Tim und Struppi) invited French automobile manufacturers to design their vision of a car for the year 1980. Tintin had a wide readership and was also read by many adults. However, not a single manufacturer responded…

At the time, Robert Opron was working at Simca and told his neighbour, Pierre Guérin, about the competition. Guérin, an astronomer and astrophysicist at the Paris Observatory, urgently urged Opron over an aperitif to convince his employer of this significant project. During their conversation, the idea emerged to choose the year 2000 as the target year for the automotive vision of the future instead—an idea that Tintin enthusiastically embraced.

Opron had been with Simca since 1957 but had so far only been involved in minor projects such as logos or hubcaps. Nevertheless, he successfully persuaded the management to develop a car for the year 2000. With the support of a colleague, he designed the two-seater concept vehicle Fulgur (French for “lightning”), and a prototype was built. It was more of a spaceship or flying saucer than an automobile. The compact and streamlined Fulgur completely abandoned the popular chrome trim of the time and already showcased Opron’s preference for flowing forms.

On December 11, 1958, Tintin published an illustrated article about the Fulgur, which—drawn by Antonio Parras—even made it to the cover of the magazine Vaillant. Until April 1959, Tintin also published the 13-part comic Les aventures de l’agent ‘P.60’: The Fulgur Affair, which explored the creation of the concept. This series was reissued a few years ago and can still be found in modern antiquarian bookshops. The Fulgur was exhibited at the Geneva and Paris Auto Shows in 1959—an excellent advertisement for Simca!

The list of anticipated features alone was remarkable, demonstrating Opron’s foresight and imagination [modern equivalents are noted in brackets]. The Fulgur was supposed to be controlled by a voice-operated computer [e.g., today’s Google Assistant or ChatGPT in DS Automobiles] and equipped with differential radar for continuous road monitoring [now realized with LiDAR and 24/77 GHz distance radar], allowing the vehicle to stop automatically when encountering obstacles [e.g., traffic jam assist]. The steering wheel resembled an aircraft control stick [similar to modern Tesla yoke steering wheels] and was intended to be controlled by traffic control towers along the roads [comparable to Google Maps or mobile networks today]. A central element of the dashboard was a clearly and ergonomically designed radar screen [similar to maps in Android Auto]. The seats were designed in the Space Age style [reminiscent of the Citroën Oli], while V-shaped “stabilizing fins” with control mechanisms [akin to modern adaptive rear spoilers] were meant to provide necessary stability.

On highways, the Fulgur was envisioned to receive power inductively through the road to drive its two in-wheel rear motors. Off major roads, six fuel cells would have provided alternative energy [similar to today’s hydrogen powertrains], and even a replaceable strontium mini-reactor was considered. This setup would have enabled an impressive range of 5,000 kilometers without refueling. Exceptional ride comfort was to be ensured by an adaptive electromagnetic suspension [similar to Bose Active Suspension] as well as stabilizing gyroscopes and speed-dependent headlight beam adjustment [now found in Audi Adaptive Light]. Passengers would be protected from harmful UV light by an almost hemispherical “radiation-filter dome” while still enjoying a perfect panoramic view, and they could individually adjust the length and tilt of their pneumatically air-conditioned seat cushions.

Until 1961, the avant-garde Fulgur was showcased at numerous automobile exhibitions, including in the United States—it is even rumored to have made it to Tokyo. In fact, it was the only European concept car of international renown during that era that could rival the almost simultaneously emerging American visions of the Space Age. Most importantly, Citroën’s chief designer Flaminio Bertoni took notice of the Fulgur and its creator, Robert Opron. When Opron applied to Citroën in 1962, he was already a familiar name.

Despite its groundbreaking ideas and spectacular debut, the Fulgur soon disappeared into obscurity, and the concept vehicle was scrapped a few years later. However, even today, an ashtray in the shape of the Simca Fulgur sits in the abandoned study of Robert Opron, a reminder of his breakthrough as an automobile designer…

Unfortunately, Robert Opron left us far too early — he succumbed to a COVID-19 infection in 2021. Sadly, he never had the chance to witness the futuristic designs that can now be realized within moments using “Generative AI”. I would have loved to hear his thoughts on what platforms like Midjourney (for AI imagery, sketches or realistic photos) or KlingAI (AI videos) produce today.

However, his creativity, the incredible diversity of his designs—created entirely without computers or the internet, relying solely on imagination, a keen eye for proportions and lines, and of course, his drawing skills—has captivated many of us. Thus, a small team of us decided to gradually document and curate his life’s work, allowing others to experience his creative legacy. Without hesitation, we founded the “Amicale Robert Opron,” officially endorsed by the Opron family, and sought an opportunity to bring this vision to life in a project.

The memory of the “50 Years of Citroën Ami 6” exhibition at the Germany Technik Museum Speyer in 2011, which I organized at the time, resurfaced, and we contacted the museum curator to explore the possibility of presenting a retrospective. The foundation was laid at Techno-Classica 2022, and in 2023, the Speyer Museum allocated a small space in the space exploration hall for this exhibition.

By winter 2023/24, thousands of visitors had already gained insight into Opron’s work. A combination of production vehicles, design objects (scale models at 1:5 or 1:10), over 420 drawings and sketches, photographs and artifacts from the Opron family archive, along with a series of presentations and films, provided a comprehensive look at his contributions.

The exhibition was divided into four thematic sections. The first focused on the industry context: the automobile manufacturers, their positioning, organizational structures, and, in particular, the design department (Bureau d’Études) and its processes, using Citroën as a case study.

Opron was not just a designer; in 1964, he succeeded Flaminio Bertoni, who had hired him at Citroën two years earlier. Opron, who respectfully called Bertoni “Master” became Citroën’s head of design. The youngest member of the department at the time, he suddenly found himself leading a team, likening his role to that of a conductor orchestrating an ensemble, which he did masterfully.

Pierre Boulanger quickly recognized Opron’s potential and favored him over Henri Dargent—Bertoni’s former right-hand man, who saw himself as Bertoni’s rightful successor but did not get the position. Dargent was too entrenched in Bertoni’s now outdated style, whereas Opron brought contemporary design language to Citroën, representing a fresh new generation of designers. Although Dargent and Opron were never close, they worked together throughout their

careers.

Opron formed personal ties with his design colleague Jacques Charreton, and their families became friends. Like Boulanger, Opron was quick to recognize the talent of American designer Henry de Ségur Lauve, in stark contrast to Bertoni, who had little regard for “HSL.” Opron integrated de Ségur Lauve as an external consultant, and many of his detailed designs influenced the interior and cockpit layout of the SM. Later, Opron formed a close collaboration with Gaston Juchet at Renault and worked extensively with Marcello Gandini, implementing numerous Renault projects. In fact, Opron pioneered what is now known as the “Agile/Sprint” methodology — pitting design teams against each other to extract the best elements from each concept and merge them into a final result.

The second section of the exhibition highlighted selected vehicle models, tracing their evolution from Opron’s earliest sketches—often vastly different from the final design—through continuous refinement to 3D realizations, including small-scale maquettes and full-scale 1:1 studies used for management presentations and project approvals. One of the focal points of this retrospective was the SM, and thanks to our collaboration with the archives of L’Aventure Peugeot Citroën DS, we were able to showcase many previously unseen SM design drafts.

The third section, titled “Curriculum Vitae,” presented key milestones in Robert Opron’s life and served as a bridge to the fourth section, which explored his tenure at various manufacturers and the landmark designs he created for them.

What many do not realize is that Opron’s designs were not only aesthetic milestones but also commercial successes. The Citroën GS (2.4 million units), CX (1.1 million), and Renault R9 and R11 (2 million combined) played crucial roles in their brands’ financial success during the 1970s and 1980s.

The Renault Fuego, produced in approximately 250,000 units, is now a sought-after classic. Yet, the R9 unmistakably retained Renault’s identity, distinguishing itself from its main competitor, Citroën. Opron had the remarkable ability to reinvent himself with each employer–exemplified by the Alfa Romeo SZ, the “Monster”, which embodies the Italian marque’s DNA like few other vehicles.

Another remarkable testament to his work is worth telling here.

The “Prêt-à-Porter” fashion show, established in 1965, is one of the most renowned fashion events in the world and plays a crucial role in presenting ready-to-wear fashion designed for the mass market. The term “Prêt-à-Porter” comes from French and means “ready to wear.” The idea behind this fashion show is to present everyday fashion, in contrast to “Haute Couture,” which consists of custom-made clothing for a wealthy clientele.

The design competition “La Femme 1972,” held as part of this fashion show in 1971, was a unique event in which nine automobile manufacturers or their designers were invited to present their vision of the woman of 1972. Monique Montagne, head of press for the fashion show, extended the challenge to famous names such as Bertone, Pinin Farina, Giugiaro, Style Renault, and, of course, Style Citroën. This competition was organized in the context of the social and cultural changes of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when women’s rights and gender equality were major topics. The participating manufacturers were asked to develop creative and innovative concepts and submit them by mid-September 1972.

Robert Opron was the only one to submit a three-dimensional interpretation: a statuette made of Plexiglas, mounted against the background of an incredibly modern computer graphic for its time. His credo: “Both in fashion and in automobile design, one should work in three dimensions from the very beginning.”

The graphic visualizes mobility and automotive design in an abstract way, while also conveying elegance and lightness. This made it stand out starkly from the interpretations of the other manufacturers, who presented significantly more conventional and two- dimensional drawings instead.

Opron later stated that the choice of material played a crucial role, as it reinforced the spatial component. Through anamorphosis—the changing perception of an image depending on the viewing angle—surprising visual effects could be achieved, as Plexiglas is both transparent and pure while remaining smooth, according to Opron.

The weekly magazine Jours de France described Opron’s work as the most intimate interpretation of the challenge, one that, in this way, once again reflected the unique and distinctive character of the brand…

If you missed the exhibition at the Technik Museum Speyer, there’s good news: since Pentecost 2024, the National Automobile Museum in Diekirch, Luxembourg (Conservatoire National de Véhicules Historiques, www.cnvh.lu), is hosting a much more extensive Opron retrospective. 22 vehicles from the Opron era, including an Opron-design tractor and the famous SZ, are on show. For approximately 12 months, Opron fans and design enthusiasts are warmly invited to learn more about Robert Opron and his work. We look forward to your visit!

Further information can also be found at www.amicale-robert-opron.org.

Finally, we would like to take a moment to highlight that the extensive work of the volunteer-driven Amicale Robert Opron can also be supported: the website provides options at the bottom to contribute small donations to help cover the ongoing costs of exhibitions, preparations, object acquisition, and transportation. So far, all efforts have been financed entirely from private funds.

Additionally, we are always looking for new exhibition pieces—whether it be vehicles for display or specific “Opron objects.” We would be delighted to receive offers and contributions. Our email address and contact details can also be found on the Opron homepage.

Thank you in advance for your support!