We came across a very sad tale of an African 2CV adventure that ended horribly. What’s more is that ironically there is a link to Amherst College in MA, where the only USA ICCCR (International Citroën Car Club Rally) was held in in 2002.

On Amherst College’s website in the “In Memory” section is a page about Yves Tommy-Martin who came to Amherst in September 1956 as a French language assistant in the Fulbright exchange program and was then admitted to the Class of 1958.

A strong student, he majored in English, wrote a magna thesis on Faulkner and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He was also more cosmopolitan than most of us. Yves had traveled in England, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Spain and Tunisia. He was a skier, a swimmer, a horseback rider and a superb cook.

Like many dreams of adventure, it began in a college bull session. John Armstrong of suburban Belleville, N.J. used to talk things over with Yves Tommy-Martin. The idea of the trip was more than adventure. It was to explore a whole new realm of experience. Yves wished to know new people, new ideas and new places. Also, he wished to know a new role for himself, one of “action” as opposed to the role of observer, which he felt as a student. Armstrong turned up in Paris on his own Fulbright to do research in Chinese literature at the Sorbonne. Their ambition now: to drive the 8,500 road miles from Paris to Johannesburg, circumvent African the continent, and then finish in Paris – the “Tour d’Afrique Franco-Americain.”

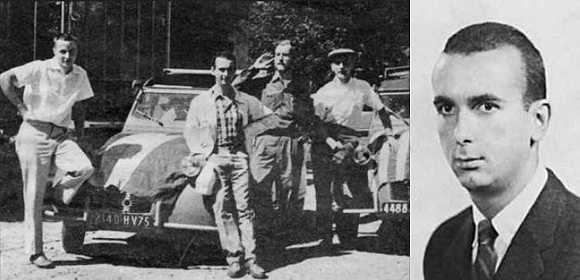

They spent the year recruiting corporate sponsors (e.g., Citroën and Michelin provided equipment, Paris Match was granted exclusive rights for the story) and recruiting two other companions — another Frenchman, Jean Pillu, 25, and another American, Donald Shannon, 28, of Milwaukee.

One other recruit was Lou Eastman, who fortunately backed out at the last minute. Lou looked up Yves in Paris in the fall of 1958. He recalls;

“Yves invited me to go on the trip. Quite uncharacteristically (then and now, given my preference for physical comfort), I accepted. Some time in spring 1959 I bought one of the two 2CV Citroëns. In May my dad visited me in Paris. He thought I might want to reconsider going given my distaste for camping (putting it simply). I talked to Yves; he was understanding. He bought the car from me.”

On July 4, 1959 they set forth from Paris in two Citroën 2CVs loaded with camping gear. They first drove to Beirut, then traveled by ship to Port Said. The plan was to drive through Egypt into the Sudan, down to the Cape, then up the West Coast of Africa, to Gibraltar, Spain and back to Paris – by Christmas.

“Africa is calling,” Donald wrote cheerily. The tour headed south to the Riviera, turned east into Italy, drove across Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey and Lebanon, and finally put their cars aboard a boat bound for Port Said. On July 24, Donald sent his sister a letter from Isna, Egypt, saying that he and his companions were ready to cross the Nubian Desert, and adding confidently “Write me in Johannesburg.” In Aswan next day, John Armstrong wrote his mother a postcard that said he would soon be in the Sudanese border town of Wadi Haifa. The four bought food and water to last three days and hired a Nubian boy to guide them through the desert.

The letter and the postcard were the last news to come from the expedition.

After they left Aswan for the Nubian Desert, the tale became shrouded in mystery. It remains so a half century later. Although they had hired a young boy as a guide for the roadless drive across the “boundless and bare” desert, they apparently became lost and ran out of water. And, according to an article in Time magazine, “ the Nubian boy they hired had never been a guide before in his life.”

The last message, penned by Tommy-Martin in diaries found later, was written in despair in early August. “We are approaching the end. Searched the entire area for water but found none.… We are all in bad shape. Nothing can save us from death except a measure of good fortune – a chance that would give life back to us.”

By early October, when no word had been received since July, a United Arab Republic patrol found the bodies of four victims, including Tommy-Martin, near their vehicles. Yves was 24 years old – the first in the Amherst College Class of 1958 to die.

The Egyptian authorities were uncooperative from the beginning. The Tommy-Martin family suggested foul play and a possible cover-up, although there were no initial signs of theft or injuries to the bodies. The family employed private detectives to research the case (France then had no diplomatic relations with the U.A.R.). They apparently found evidence that one of the cars had bullet holes in its side.

As late as 1979 Amherst College Alumni Secretary Al Guest was in touch with Tommy-Martin’s sister, still investigating the case. She had written Guest that an autopsy later conducted on her brother “revealed broken bones.” So no one could say with certainty what happened. The sister told Guest; “Maybe the unknown is better.”