By Per Ahlstrom…..

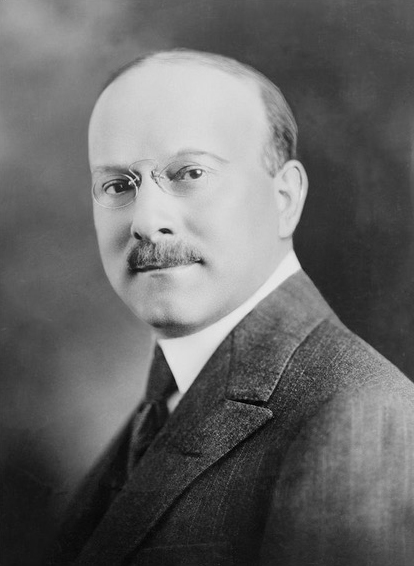

When the Citroēn bankruptcy in 1934 is discussed, André Citroën’s penchant for gambling is often mentioned as a reason for his financial problems. The truth is that if anything, his penchant for gambling prolonged the life of his company for years. It was ripe for bankruptcy in 1930 due to events beyond André Citroën’s control.

Citroën’s automobile venture was undercapitalized from the start in 1919. This is why André Citroën wooed Ford and GM, asking them to take a major ownership position in his company.

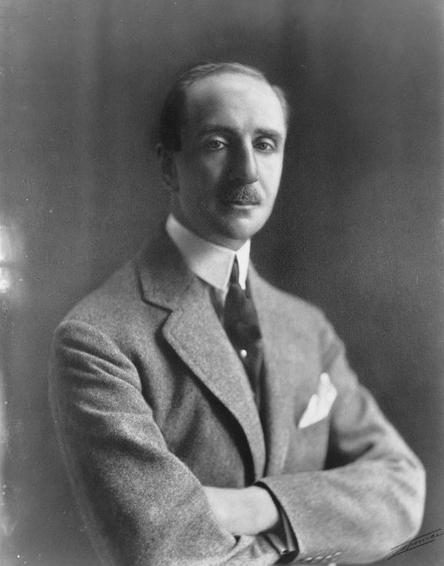

Ford and GM turned him down. Alfred P. Sloan, who ran GM from 1924 to 1956, was a member of the GM delegation who went to Europe in 1919 searching for a European car company to buy. After meeting with Citroën and studying his operation, the GM delegation turned down his offer. They did not think his management team was strong enough, and they didn’t find his converted munitions factory suitable for automobile production.

As Citroën could not find investors that could put up enough capital to secure the establishment of automobile production, he became very dependent on banks and other creditors. All through the 1920s his company was profitable and expanded rapidly. Profitability is not the same thing as stable finances. Rapid expansion is a common cause for bankruptcies.

Expansion requires capital to be invested up front in machinery and raw materials and to pay for running expenses until customers pay for the finished products. If the company continues to expand rapidly, the gap in time between expenditures and income grows bigger and bigger and it is very difficult for even very profitable companies to keep up without support from banks, suppliers and subcontractors.

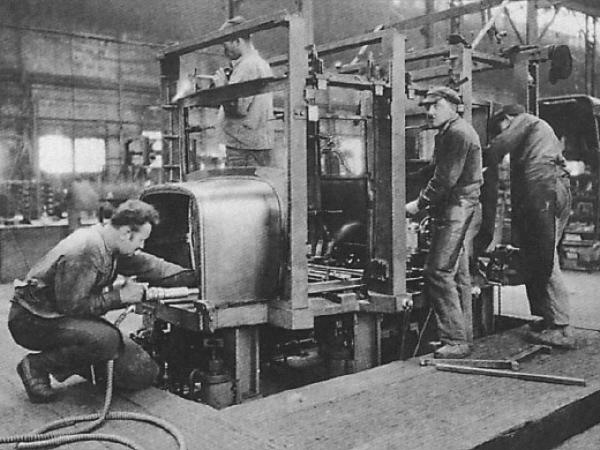

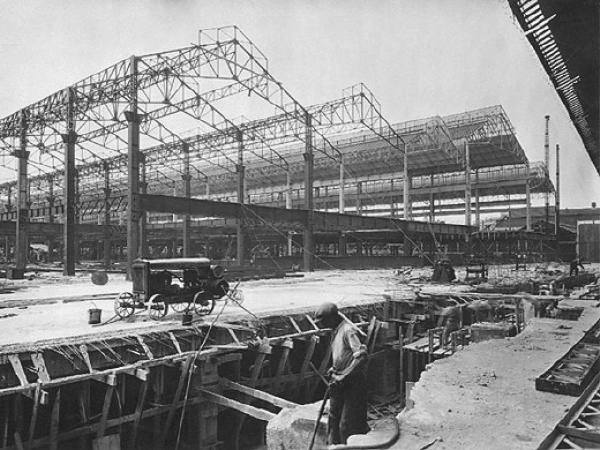

The strategy André Citroën adopted accentuated this problem. The all steel bodies required huge up-front investments in machinery and tooling. It was more economical than the old way of building car bodies, with steel sheets nailed to a wooden frame, if the cost of machinery and tools could be dispersed over a large number of cars. Citroën achieved this economy of scale throughout the 1920s and in 1929 Citroën produced more cars than any other European manufacturer and sold over 100,000 cars.

This success was partly due to a huge investment he made in the new 1929 models, models that required major retooling. Everything seemed to be running well and Citroën had no problem borrowing money to assure sufficient liquidity.

The drawback of Citroën’s strategy was that the company lost a lot of financial flexibility. A drop in sales could not easily be met with reductions of costs. The interest on the loans Citroën took to finance the up-front investments in machinery and tooling had to be paid no matter how many cars the company made. They were fixed costs that the company could not change.

Citroën was also dependent on importing steel for the bodies from the U.S. The French industry could not produce steel sheets of the quality needed for the American presses that Citroën had installed.

His main competitors, Renault and Peugeot, had chosen a more conservative strategy. They invested in mass production facilities, but kept the traditional way of building car bodies. They had higher running costs for materials and labor than Citroën, but their fixed costs were lower, as woodworking machinery was much cheaper than the huge presses Citroën had bought. If sales dropped they could rapidly reduce their costs, as they needed less material and could rapidly cut down the workforce. They also had no need to import steel, as the composite auto bodies did not necessitate the same high-quality steel as did the Citroën presses. They also spread their risks by producing more models in different price classes, while Citroën relied on one basic model, but with different size engines.

Up until October 1929, the Citroën strategy was very successful and the future of the company looked very bright. But when the American stock market crashed, Citroën’s situation changed dramatically — practically overnight.

The French government raised the import levies on imports to 30% in order to protect the French industry from the global depression they saw coming. This protected Renault and Peugeot, but it was a hard blow to Citroën who was totally dependent on imports of steel and components from the U.S.

Citroën tried to counter the higher costs for imports by making the cars lighter, thus using less raw materials, and by negotiating prices with his American suppliers. He sent his deputy Georges-Marie Haardt to America in 1930 to discuss simplified and lighter body designs with Budd and to re-negotiate the contracts Citroën had with suppliers of components.

He was somewhat successful, but as the sales went down from 100,000 cars in 1929 to 70,000 cars in 1930, there was very little Citroën could do to cut costs in a way that could even come close to compensating for the double whammy of increased costs by 30 percent and decreased sales by 30 percent. The company was on the verge of bankruptcy.

This is when André Citroën made his big gamble.

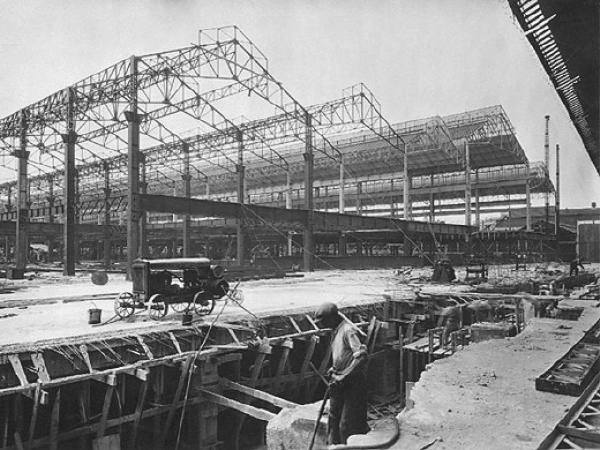

He was stuck with high capital costs, high material costs and a production facility that was far from optimal. He had a choice between declaring bankruptcy or bet on a new car (the Traction Avant), that was cheaper to produce. It had to be much lighter than conventional cars and it had to be produced in a more rational way than could be achieved in the old former munitions factory.

Citroën decided to try to save his company by developing this new car and build a new factory for its production. This was a decision he could not make by himself. He needed to convince his investors, his creditors and his suppliers that this daring venture was their best bet to recover the money they had invested in his company.

He got support from La Banque de l’Union Parisienne, Credit Lyonnais, the two machine manufacturers Stokvis and Fenwick, the steel industry, represented among others by Châtillon-Commentry and le Comptoir Sidérurgique de France, subcontractors like Chausson, Budd, Jaeger and Mobil Oil, which offered a loan of up to 25 million francs. In December 1934 at the time of the bankruptcy Citroën owed 425 million francs to the creditors.

The creditors were of course aware that they were taking a big risk. When the creditors offered their support nobody knew how long and deep the depression would be, but the creditors obviously thought they would be able to wait for Citroën to turn stable profits again. They were wrong.

The house of cards started to crumble when one of the major creditors, La Banque de l’Union Parisienne, ran into financial problems of its own. Citroën pressed on with the development of the Traction Avant, but as we now know, he lost the race against time. In the fall of 1934 it was clear that some major creditors could no longer afford to wait. They needed to recoup as much as possible of their investments as soon as possible and Citroën was forced to declare bankruptcy.

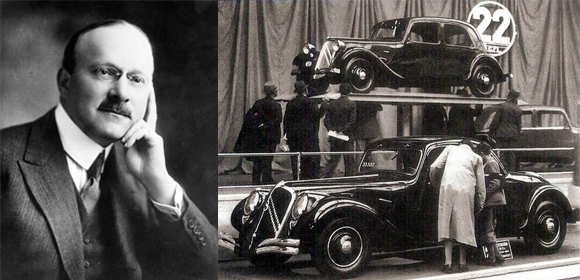

It is noteworthy that Michelin, the biggest private creditor, who took ownership of Citroën after the bankruptcy, still had trust in André Citroën. On January 10, 1935 the bankruptcy court demanded that André Citroën resign as CEO of the company, which he did on January 31. But on demand from Michelin he stayed on as Chairman of the Board, a post he soon had to abandon due to his poor health. He suffered from cancer and was worn out by the stress put on by the financial difficulties and the radical transformation of his business. He died on July 3 1935 and was succeeded as chairman of the board by his long-time friend Félix Schwab.

Michelin made some radical changes to the Citroën business in order to make it profitable. Michelin realized that productivity had to be improved. To be profitable Citroën had to build at least 600 cars per day, but in the beginning of 1935 only produced 300 per day. The engineering of the car had to be improved, not only to make customers more satisfied, but also to cut down on the costs for recalls and adjustments. The production of the car had to be streamlined, which was not surprising considering how pressed Citroën was for time when the new factory began producing the new car.

Michelin also made considerable cuts in the business activities of Citroën that were considered to be secondary. Advertising was cut back, the number of sumptuous showrooms was reduced, the dealerships and manufacturing facilities both in France and abroad were reorganized and were run on a more modest scale. Non-profitable facilities were permanently shut down. The side businesses, the taxi company, the insurance company and transportation company were sold off. The dealership contracts were re-negotiated and Michelin managed to negotiate a reduction of the credits the dealers had extended to Citroën, by 75%. Michelin’s negotiations with the creditors resulted in an agreement that cut down the short term debt by 660 million.

Michelin also attacked the running costs, reducing the workforce from 25,000 employees in late 1934 to 11,500 in June 1936 – a more than 50% reduction. Activities like the architectural service and installation services were minimized. Wages and salaries were reduced by between 5% and 30%, and overtime was not paid.

Michelin’s calculations showed that they needed to reduce the monthly payments by 47% while only cutting back the manufacturing capacity by no more than 23% to make Citroën profitable. This reduction in production capacity was not random. It was merely an adaption to the market conditions. Only the temporary reduction of vehicles in stock, 7,300 at the outbreak of the bankruptcy, freed up 110 million francs.

At the same time as Michelin undertook these financial measures, American methods for reducing waste and increasing productivity were introduced. The stocks of materials and cars were rigorously controlled and minimized. The main focus was on increased productivity, and between June 1934 and June 1936 the number of man-hours to build a Traction Avant body was reduced from 955 to less than 500. The high efficiency of the American machinery worked wonders, but Michelin was not satisfied with just getting things to run smoothly. They wanted to pass on the cost reductions to the customers, in order to stimulate sales. Thus Citroën lowered the prices in October 1935 by between 3 and 14%, or 500 to 3,500 francs per car. This helped production increase from 40,000 in 1935 to 61,000 in 1937.

In 1937 the shareholders got a dividend for the first time since 1933. Citroën was once again the biggest car company in France. The company had been saved.

Thus the soundness of the Citroën business was proven. We will never know if André Citroën had been able to make the drastic cost reductions, sell offs and rationalizations without the help of Michelin. And we will never know if it had been timely or even possible to make some or all of these changes before the bankruptcy was a fact. But no matter what, the company he built was saved and profitable and had once again a bright future.

To conclude: The 1934 Citroën bankruptcy was not caused by André Citroën’s gambling at the casino in Deauville. It was not due to an irresponsible decision by André Citroën to invest in a new car and a new factory. The bankruptcy was the end result of the unexpected double whammy that hit Citroën in 1929/30, with import tariffs raising the cost of materials by 30% and the depression cutting sales down by 30%.

That the bankruptcy didn’t happen in 1930 was because banks and suppliers supported Citroën’s decision to try to save the company with a radical new car built in a radical new factory. The alternatives were either a sudden death in 1931 or a slow death that would be long and painful, but inevitable. The end result was that Citroën brought his company to a stage that made it possible to save after the bankruptcy and that his life’s creation lived on as an independent company for another 40 years.

This article is based on the findings of Jean-Louis Loubet, professor of contemporary history at the University of Évry in France, presented in his book “Citroën, Peugeot, Renault et les Autres – soisante ans de stratégies”, Le Monde-Éditions, Paris 1995.

An excellent article on the actual reason for André Citroën’s

‘gambling.’ He gambled on his newly designed automobile, not at the casino. André Citroën was a man of vision.

Great article for Citroën lovers !! Thanks!!

Greetings from Santiago Chile

My father had a Traction Avant. It had fantastic pulling power in the desert roads of Alexandria. Where rear wheel drive vehicles would get bogged down the Citroen sailed through. The front windscreen had a screw arrangement to open it letting cool air come in. The windscreen wiper had a manual knob to turn if the motor seized. It had a starting handle if the battery died. It never ever stopped. You could use womens stockings if rubber belt from engine to water pump dynamo broke. Citroen comes from the Jewish feast of Succoth where we buy palm leaves and Citron so people who sold these were called Citron now mainly in Morocco but then was Italy also. Jews are risk takers and they are the yeast in flour to make bubbles transforming to bread.