By Stephan Joest….

In 2025, we mark fifty years since the end of production of one of the most daring, ambitious, and potentially misunderstood automobiles ever created — the Citroën SM.

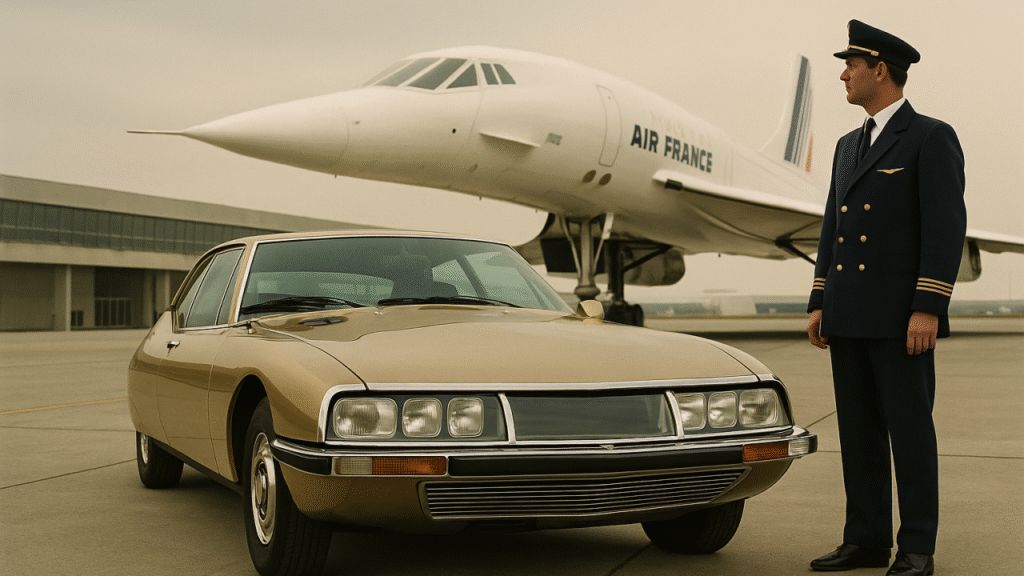

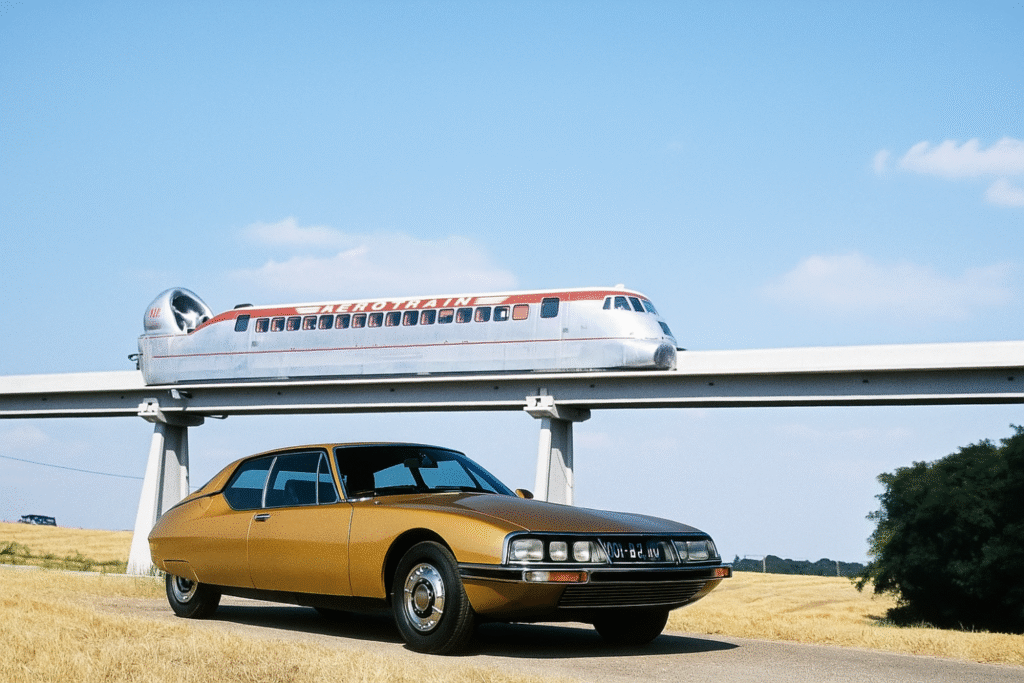

Built between 1970 and 1975, the SM remains an enduring symbol of that unique moment in European history when innovation seemed limitless, and optimism was an industrial value. It was an era that believed, quite literally, that the sky was the limit — from the Aerotrain development, the predecessor of the TGV train, to the first humans walking on the Moon – and another milestone materialized, the Concorde supersonic airplane.

The SM, born from this same cultural current, can certainly be perceived as the “Concorde of the Road“ — a machine that embodied not just speed and luxury, but also a poetic confidence in technology, design, and the future.

A Dream in Motion: Origins of the SM

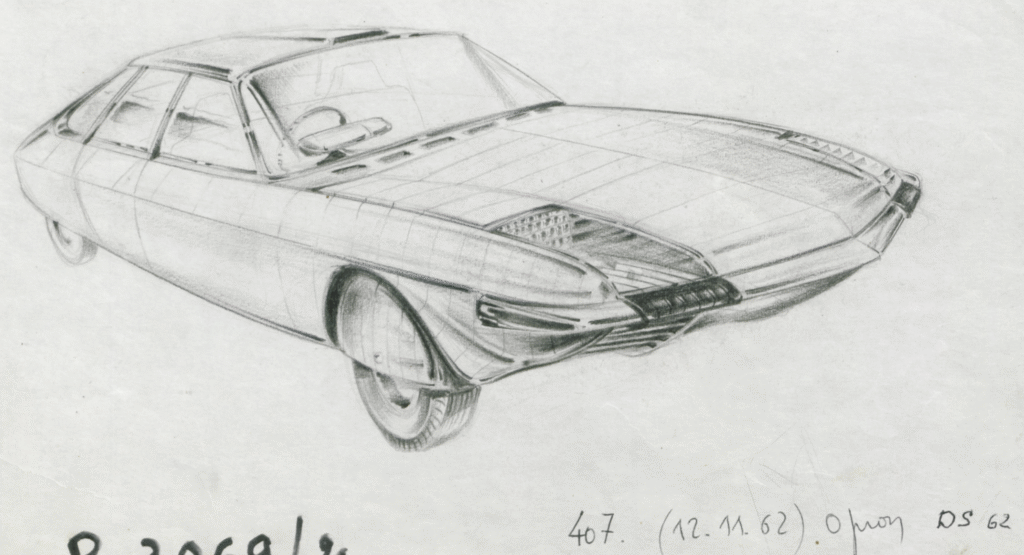

The Citroën SM project already began in the early 1960s, in an environment of profound creativity. Citroën had already stunned the world with the DS in 1955 — a car that seemed to have landed from another planet. Less than decade later, the challenge was how to go even further.

Under the direction of Pierre Bercot and Robert Puiseux, Citroën envisioned a car that would carry the DS philosophy into a new decade: a grand touring coupé that would merge French design flair with world-class performance. The initials “SM” likely stood for Série Maserati — initially the “S” was reflecting the “Sport” evolution of the DS limousine — and the “M” then being a nod to the Italian engine collaboration that defined the project’s heartbeat.

In 1968, Citroën acquired a majority share of Maserati, with the strategic intent of combining the French mastery of suspension and aerodynamics with Italian performance engineering. The result was a 2.7-liter (later 3.0-L electonic injection) Maserati V6 — light, compact, and exotic — installed under the elongated bonnet of a front-wheel-drive grand tourer.

But it was not only the engine that made the SM remarkable. It was the sum of its parts — and the philosophy behind them.

Design and Philosophy: Opron’s Vision

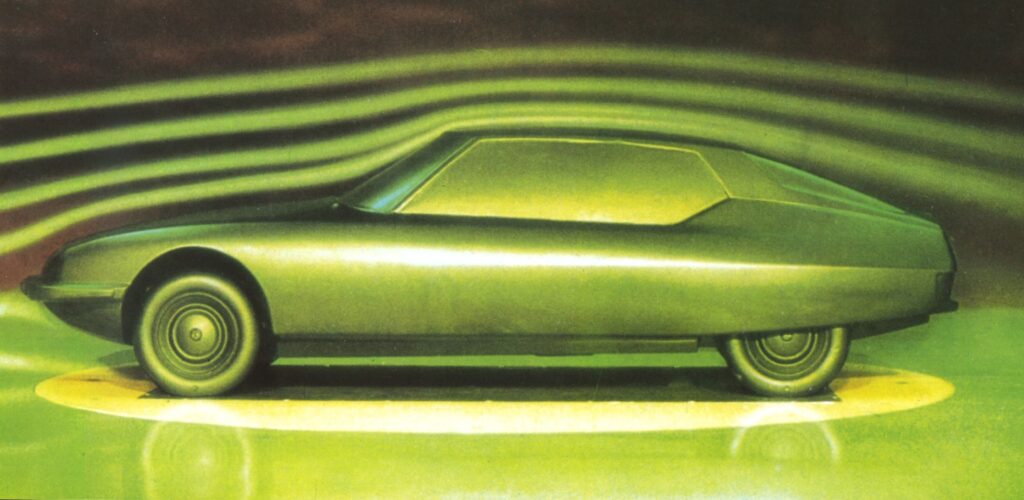

Robert Opron, since 1964 Head of Design at Citroën, conceived the SM as an architectural sculpture on wheels. Having succeeded the legendary Flaminio Bertoni, Opron carried forward the idea that a car should express a philosophy, not just a function.

The SM’s shape — long, tapering, aerodynamic — was defined by airflow, not ornamentation. With a drag coefficient of 0.33 (unheard of for its time), it seemed to slice through the air as naturally as a jet. The six headlamps hidden behind glass, two of them swivelling with the steering wheel, gave the car a human, almost sentient presence. Its teardrop silhouette echoed the aerodynamic experiments of Paul Arzens and the futuristic optimism of 1960s France (and, by the way, this form was the only way to achive the speed of almost 230km/h, making it world’s fastest coupé: the German competition, notably Mercedes-Benz AG, had the better engine, but not the aerodynamics as good as the SM…!)

(C) Citroën Communications / Amicale Robert Opron

Opron once said that cars should “move the spirit as much as they move the body.” I had the privilege of knowing Robert personally over more than two decades — exchanging reflections with him on automotive design and cultural meaning, e.g. when he followed my invitation to visit the “Techno Classica” historic vehicle exhibition in the 2010s together with his wife Geneviève: he always studied how others had designed vehicles. Those conversations revealed how deeply he saw cars as living art, but also combining function with comfort for passengers — and the SM as perhaps his purest expression.

Technology as Poetry

To understand the SM is to understand how technology became poetry in motion. Its hydropneumatic suspension delivered a ride so smooth it seemed detached from gravity. The variable-assist DIRAVI steering was so light at low speed and so firm at high speed that it felt telepathic. The braking system, with its characteristic “mushroom” pedal, demanded precision and rewarded confidence.

Everything about the SM was designed to redefine the grand touring experience: silent at 200 km/h, stable on any surface like being on a train track, and composed in a way no rival could match. This was not just a fast car — it was a fast philosophy.

The SM in Context: Concorde, Aerotrain, and the Age of Elegance

In the 1970s, France aspired to lead the world in engineering audacity. To call the SM “the Concorde of the road” is more than a metaphor. Both projects — the supersonic jet and the Citroën coupé — were designed at a time when Europe sought to reclaim global prestige through design and technology. Both were collaborative triumphs of mechanical engineering and aesthetics. Both were admired, envied, and ultimately victims of economic realism.

Like the Concorde, the SM was a technical masterpiece whose timing collided with a changing world. The 1973 oil crisis, rising insurance costs, new regulatory obligations in the U.S. market where a major share of vehicle were foreseen to be sold, and Citroën’s financial instability brought an abrupt end to production in 1975.

Yet, in that short span, just 12.920 cars were built — each one a capsule of that unique cultural moment.

To drive an SM today is to feel what the early 1970s felt like — the sensation that progress was not only possible but desirable. It was an era that saw design as destiny, not decoration.

A Legacy Beyond Numbers

The SM’s legacy extends far beyond its production figures. It defined an entire generation of designers, engineers, and enthusiasts who came to see cars not just as transport, but as cultural artefacts.

It also redefined the idea of luxury. Where German manufacturers built luxury around power and prestige, the SM built it around refinement, intelligence, and grace. It was a car for thinkers, architects, and musicians — people who appreciated silence, balance, and motion as art.

This cultural dimension of the SM aligns perfectly with the mission of organizations such as FIVA (Fédération Internationale des Véhicules Anciens), which advocate for the recognition of historic vehicles as part of our global cultural heritage. In the SM, we see the synthesis of art, science, and human ambition — a guiding example of what “automotive culture” truly means.

Personal Reflections: Lessons from Robert Opron

Exhanging thoughts with and learning from “the master” Robert Opron gave me an insight into the mindset behind such vehicles. He saw the SM as more than a car — he saw it as a conversation between past and future.

During our exchanges, he reflected that “designers of the 1960s were not constrained by feasibility — they designed for what should exist, not just for what could”. That mindset remains a challenge to us today, in a world often driven by algorithms and cost-efficiency.

The SM teaches us that creativity, when guided by conviction, can become timeless. Its technology may age, but its philosophy never will.

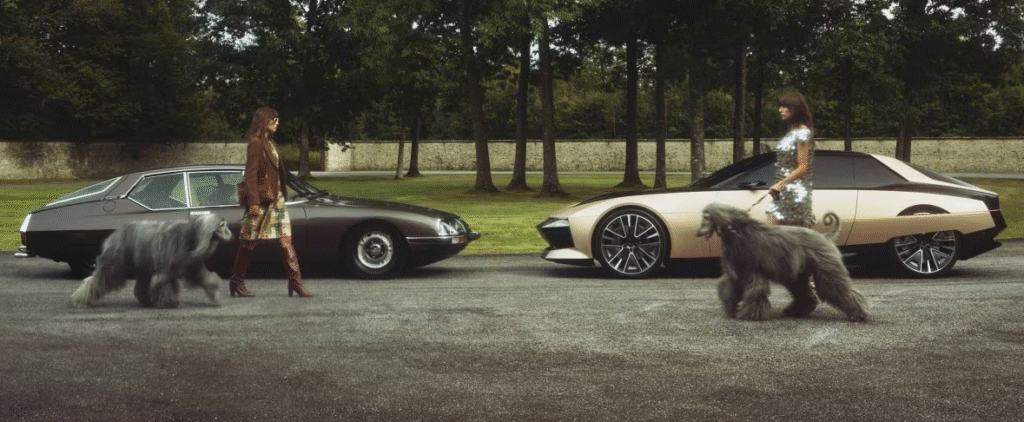

From SM to DS Automobiles: A Living Lineage

In many ways, the modern DS Automobiles brand inherits the DNA of the SM. Both share a belief that innovation must serve emotion — that advanced technology should create serenity, not stress.

DS Automobiles’ pursuit of electrified performance, handcrafted interiors, and avant-garde design is a modern continuation of Citroën’s golden age. Where the SM used hydraulics and aerodynamics to achieve harmony, DS uses electrification and digital craftsmanship. But the ambition — the courage to redefine luxury through innovation — remains exactly the same.

That continuity matters. It demonstrates that automotive heritage is not nostalgia; it is the foundation for reinvention.

In 2015, I had the chance to connect the DS design head, Thierry Metroz with Robert Opron, at the occasion of a special exhibition in the Musée du Louvre garden — connecting history to the future — and the “SM Tribute” is potentially one of the best realizations by Thierry to see this link becoming alive.

The SM as a Cultural Compass

Today, when the automotive world faces questions of sustainability, identity, and transformation, the SM stands as a reminder of what vision can achieve. It is a cultural compass — pointing us toward a future where emotion and intellect coexist in mechanical form.

Historic vehicles like the SM are not relics; they are reference points. They teach us to be bold, to balance rationality with wonder, and to believe that design can shape society.

For Citroën, DS Automobiles, FIVA and the global historic movement, such vehicles are essential ambassadors. They embody the continuity of human creativity — a continuum from the past into the future of mobility.

Fifty Years After: The Meaning of 2025

In 2025, as we mark half a century since the SM’s production ended, we also celebrate the survival of its ideals. Many of the technologies that once made the SM seem otherworldly — active suspension, steering feedback, aerodynamic efficiency — have become everyday reality. Yet few modern cars express them with the same poetry.

This anniversary is not just about a milestone in history; it is about reasserting the value of imagination in engineering. The SM’s lesson is clear: progress needs courage, not only competence.

And as we look to the next fifty years of mobility — with electrification, autonomy, and artificial intelligence reshaping the landscape — the SM invites us to ask a timeless question: Can technology still move us, emotionally?

The answer, as the SM reminds us, must always be yes.

Epilogue: A Personal Note

Every time I see an SM, I see not only a car, but a conversation — between people, eras, and ideas. For me, it also represents a personal thread through my own journey in the world of automotive heritage, with focus on vehicle design and what automotive culture is about.

My long friendship and collaboration with Robert Opron shaped much of my understanding of how history and innovation intertwine. The SM is a masterpiece that continues to inspire my work in fostering connections between heritage, culture, and industry. It also inspired me to co-found the Amicale Robert Opron : sharing the legacy of a very humble genius who never wanted to be on any stage to a broader audience (see also www.amicale-robert-opron.org).

Fifty years after its farewell, the Citroën SM remains more than a design icon. It remains a living argument for why automobile culture is human culture — and why preserving that legacy is not just a matter of memory, but of meaning.

Happy 50th anniversary to the Citroën SM — the Concorde of the road, and the eternal symbol of a time when the future still belonged to dreamers…!

Text: Stephan Joest, Amicale Robert Opron.