Citroën and Oltcit — A Romanian Collaboration Leading to the Birth of Axel

By Thomas Urban….

In the mid-1970s, the Romanian government launched a new call for tenders to manufacturers in “capitalist” countries. This time, Citroën won. What allowed the brand to win this contract, against other competitors like Volkswagen, was that, like Renault before it, Citroën had the foresight to present the Romanian state with a vehicle whose design was already fully finalized (on paper, at least) and thus ready for production.

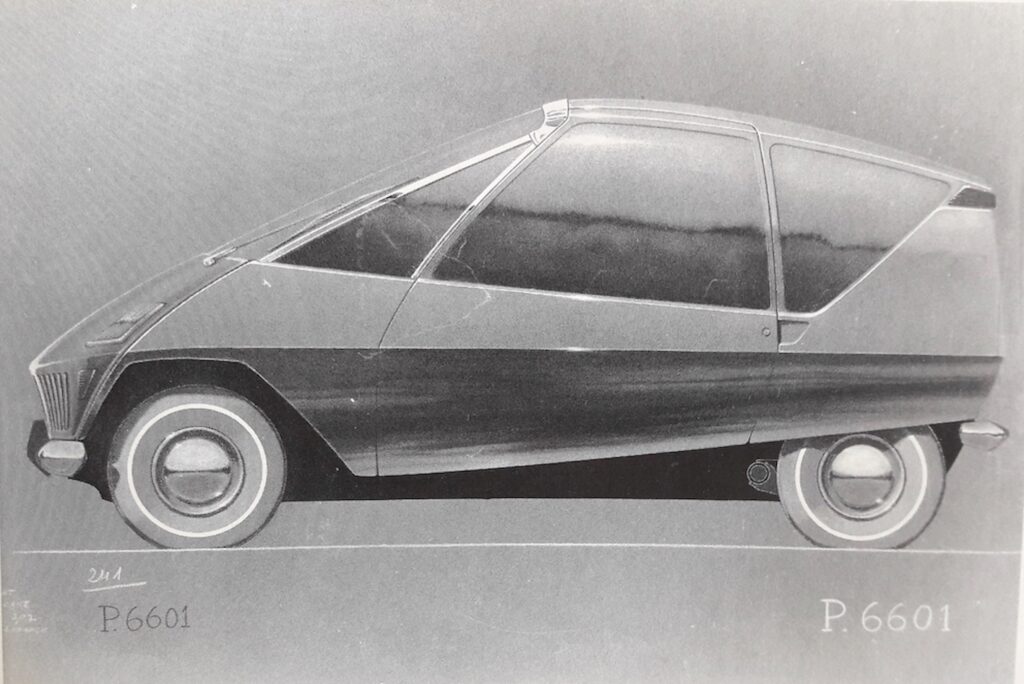

The Citroën Prototype Y was a project to develop a replacement for the Citroën Ami, conducted by Citroën in the early seventies. It built on the Citroën G-mini and EN101 projects.

From 1965 Robert Opron worked on the Citroën G-mini prototype and project EN101, a replacement for the 2CV, using the flat twin engine from the 2CV. It was supposed to launch in 1970. The advanced space efficient designs with very compact exterior dimensions and an aerodynamic drag co-efficient Cd of 0.32, were axed because of adverse feedback from potential clients.

The chairman of Citroën’s board of directors, Georges Taylor, was supportive of this project as he was from Romania, born in the country’s capital Bucharest. He maintained close ties with his homeland. Many Citroën executives saw this as an unexpected opportunity to give the ‘Project Y’ a second chance as their way to seek revenge on Peugeot’s management, who had tried to bury the project in favour of the Visa. The latter, in their eyes and those of some customers, was considered a “bastard” model. Furthermore, the Y prototype’s key technical features, such as its soft suspension and air-cooled engine, made it a highly versatile model that would only require minor modifications to adapt to the driving conditions on Eastern European roads.

In October 1970, Citroën launched the GS, finally filling a gap in the market. Before this, its lineup consisted of only the 2CV and Ami 8 on one side, and the DS family on the other. While, at the dawn of the 1970s, the Javel-based manufacturer could boast a complete range covering the main categories of the French automotive market, the company knew that, despite the rapid success of its new “mid-size” sedan after a rather difficult and chaotic development, it couldn’t afford to rest on its laurels.

The 2CV was still very successful, despite its age (launched in 1948), while the Ami 8 achieved very good sales figures despite appearances that it was merely a more modern body derivative of the 2CV with a more spacious interior and a slightly larger air-cooled two-cylinder engine.

While both models had a few years of life left, management knew they had to start planning its replacement. They shared the same opinion as the design office — they could no longer simply offer customers a “mere” derivative of the 2CV, with a modernized body. In many respects, they would have to start from scratch.

In 1974, while the Y project was in final development phase, it fell victim to the economic climate and the significant upheavals its manufacturer was experiencing. Citroën was in serious financial trouble with the late launch of the GS, the acquisition of Maserati in 1968 with the aim of offering a “noble” engine in the SM, the poor sales of the SM as a result of the oil crisis having just erupted, as well as the economic and commercial disaster of the rotary engine venture (with the M35 prototype, then the GS Birotor and the Comotor subsidiary).

Michelin, which had owned Citroën since 1934, decided to withdraw. The brand was then acquired by Peugeot. The Italian Fiat group had expressed interest in buying the Citroën brand, but the government at the time was determined not to see this flagship of the French automotive industry fall into foreign hands.

While not entirely averse to all forms of innovation, Peugeot was nonetheless considered at the time to offer both durable and comfortable cars that emphasized well designed practicality. It should be noted, however, that in terms of style, the example of the “Sochaux Spindle” line of models—202, 302, and 402—produced in the 1930s, proved that Peugeot, too, could be bold throughout its history. With their conventional and economical model offerings in 1970 and through the oil crisis Peugeot fared better. It didn’t take long for the new owner to take drastic measures to stabilize the finances of Citroën.

One of the essential measures, quickly implemented by the Sochaux manufacturer, was to cut off all the “sick branches.” This meant getting rid of models that weren’t profitable enough, such as the GS Birotor and the SM, as well as projects deemed unprofitable. It also eliminated elements that risked (too much) competition with its own models. This last reason, along with the rationalization of production costs, undoubtedly explains why Peugeot decided to end Project Y. Indeed, this new model could overshadow its own city car, the Peugeot 104, which was experiencing a rather difficult start to its career against the Renault 5 and the Volkswagen Golf. Despite this abandonment, PSA management decided to launch a study for a new project, which was in fact an evolution of the Y model, with an adaptation of the Peugeot 104 platform and its engines.

Rechristened Project VD (for “Véhicule Diminué,” a rather unflattering nickname for a car, even a popular one), its first version planned to reuse the suspension system designed for the Y prototype, adapting it to a body derived from the Peugeot 104. The result was reminiscent of the project’s first prototype, which was based on the Fiat 127. However, in the interest of standardization and cost savings, Project VD ultimately adopted the entire running gear from the Peugeot. This new model, named Visa, launched in 1978, featured lines heavily inspired by Project Y.

As initially planned, its base versions used the air-cooled two-cylinder engine from the Ami 8. Its higher-spec versions, however, used the four-cylinder engine from the Peugeot 104.

At Citroën, many of the company’s managers could not bring themselves to see Project Y simply thrown away. Indeed, it represented a huge investment, not only financially but also in terms of the number of working hours dedicated to the project. However, a new, unexpected opportunity would soon present itself for Project Y, coming from the other side of the Iron Curtain. Since the early 1970s, following the example of other Western manufacturers since the détente that began between East and West (following the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962), many Western manufacturers decided to try their luck in the Warsaw Pact countries. Fiat (which was undoubtedly the most prolific in this regard) teamed up with Lada in Russia, Polski-Fiat in Poland, and Zastava in the former Yugoslavia, which themselves wished to create or develop their automotive industries.

The Socialist Republic of Romania, then ruled by the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, had already received France’s contribution in laying its foundations in the 1960s. The country entered into a partnership with the Renault National Factories to create the Dacia brand, named after Dacia, the name of Romania during the Roman Empire. Produced in Pitesti, in a factory also built with the help the French brand, the Renault 12, sold as the Dacia 1300, quickly became a cult classic there. It spawned numerous derivatives that its French counterpart never achieved: a five-door hatchback, a coupé, as well as utility versions such as single and double-cab pickups. In fact, it enjoyed a much longer production run than the R12, with over 2,278,000 units manufactured until 2006.

Citroen’s venture to take Project Y into Eastern Bloc markets was endorsed by the French government, particularly the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (through Georges Falconnet, then Director of International Trade). He was rather favorable to the Romanian regime, which had begun to distance itself from the Soviet Union. Negotiations began in June 1975 (just a few months before the initially planned launch date of the Y prototype) with representatives mandated by the Bucharest government. The prototype was presented to President Ceausescu himself by Georges Taylor on October 25th.

Difficult negotiations meant that an initial agreement was only reached in July of the following year, for the production of the model in Romania and the construction of a new factory dedicated to its manufacture. This agreement stipulated, in addition to Citroën transferring the car manufacturing license to the Romanian state, the construction of a turnkey factory which must be operational by 1980. When it reached its optimal production capacity, the factory was expected to employ approximately 7,000 people and produce 130,000 cars per year.

The site chosen for the construction of the new factory was located in Craiova, in the province of Oltenia. Propaganda from the communist regime claimed that President Ceausescu chose the location. (This is undoubtedly no coincidence: he was from this province.) The factory was to be managed by a company jointly owned by Citroën, with a 36% stake, and by the Romanian state holding a 64% majority of the remaining shares. While the French manufacturer was ultimately only a “minority shareholder” in this venture, the financial commitment it made is equivalent to 76 million euros today.

The agreement stipulated that Citroën would market 40% of the vehicles produced in France and other Western European countries. This served as compensation for the numerous mechanical components imported from France. Oltcit, the Romanian brand, would handle the marketing and distribution of the model in Romania and the Comecon countries. The potential marketing of Oltcit in other markets, according to the agreement, would be discussed on a case-by-case basis and divided between Citroën and Oltcit based on the size of each company’s sales and service network.

Even before its commercial launch, its production already represented a significant commercial success, not only for Citroën but also for a large number of French companies involved in the project. This initiative led to the creation of 1,200 new jobs at Citroën, as well as the creation of 2,500 new jobs in France within the automotive machinery, equipment and accessories sectors. This industrial sector was suffering from underemployment at the time (due to the energy crisis of late 1973, with soaring oil prices and economic recession).

As is its custom before the official presentation of a model to automotive journalists, Citroën reduced its communication to the bare minimum. One could even say it maintained radio silence regarding this project. While some media outlets, in France and abroad, eventually caught wind of the project, the articles concerning this new Romanian Citroën in the late 1970s and very early 1980s only provided assumptions from what was gleaned from information about the prototypes.

To surprise the market and target audience, the Italian monthly magazine Quattroruote, in two articles published in November 1979 and June 1980, suggested that it was a “piccola coupé” derived from the GS. Meanwhile, in France, around the same time, the magazine L’Automobile published several photos of one of the prototypes in an article whose title clearly expressed the uncertainty: “A Two-Door GS Visa.” The journalist admitted his doubts, writing that “On this very particular model, we are lost in conjecture because it is difficult to place it,” concluding: “Where will this future model be positioned?”

The official Oltcit was presented at the Bucharest Fair on October 15, 1981, with sales announced for the beginning of the following year. Compared to the Y2 prototype from which it was derived, the main difference, both practically and aesthetically, was the reduction in the number of doors from five to three (including the tailgate), for reasons of “industrial simplification.”

The manufacturer had already announced plans for a more sophisticated version, intended for the Western market, and available after 1983. The model was marketed in two versions: the Oltcit Special, equipped with the 652cc two-cylinder engine from the Visa, and the Oltcit Club, which received the 1,129cc flat-four engine from the GS.

While the presentation of this new Franco-Romanian people’s car was widely covered by the Romanian press, including Autoturism, the only magazine there dedicated to automobiles, in France and other Western European countries, the praise was much more muted. For example, in the November 1981 issue of L’Automobile magazine, mention of the Oltcit was buried on page 68 and described as a “cross between the GS and the Visa.”

The press kit provided by Citroën was rather incomplete regarding the “Western” version of the vehicle. It emphasized the new factory built specifically for its production in Craiova, as well as the resources deployed for its equipment. On this point, the manufacturer certainly didn’t skimp! It boasted about state-of-the-art machinery for stamping, body assembly, fitting, and painting, that rivaled the recently commissioned Aulnay plant in France. The accompanying photos in the press kit featured a brand-new Oltcit Club, painted in a vibrant orange-red, photographed in Craiova’s People’s Park (designed in the early 20th century by the French architect Edouard Redont), as well as at a potter’s workshop in the Horezu region of Wallachia province (the heart of Romanian pottery, renowned since the Middle Ages), and finally at the monastery in the same town, founded in 1690 by Prince Constantin Brancovan. The photos showed a young couple, one of whom is a Romanian employee of Oltcit, dressed in traditional costume. Clearly, no detail had been overlooked in emphasizing the car’s Romanian roots.

Touting the success of the future Franco-Romanian model, Citroën executives and their Romanian counterparts were now envisioning increasing production to 300,000 vehicles per year.

Although production did begin at the start of the following year, the beginnings were nonetheless arduous. The factory encountered difficulties in obtaining raw materials, poor-quality parts were supplied by Romanian subcontractors, and the workers, hastily recruited and trained, lacked experience. The Craiova factory was actually located in a rural area, and this new workforce returned to the fields after their workday. The manufacturing quality of a large proportion of the cars produced was woefully inadequate, even by the standards in force in Eastern European countries. Thus, some cars had to be partially or completely disassembled and reassembled almost immediately after rolling off the assembly line.

All these numerous and recurring problems led to significant production delays, far from reaching the 130,000 units per year hoped for in the long term by Citroën executives and the Romanian government. To say that production rates were far below forecasts is an understatement, because by the end of 1982, only 7,915 cars in total had rolled off the assembly lines. The results for 1983 were hardly any better, since at the end of its second year of production, the Craiova plant had only managed to produce around 8,500 units.

It wasn’t until 1984 that production took off significantly, reaching 20,000 units. This increase in production stemmed primarily from the fact that Citroën, honoring its commitment to its Romanian partners, launched the Oltcit in France and other Western countries at that time.

In order to promote the Oltcit’s image, a competition department was established, and the model participated in numerous events in Eastern Bloc countries, such as the Golden Sands Rally in Bulgaria. The Oltcit also distinguished itself in several Western rallies, its greatest success undoubtedly being the 1985 Lebanon Rally (where the model competed in the Group A category). Unfortunately, apart from this and a few other isolated cases, the Oltcit’s sporting career barely reached beyond the Iron Curtain.

Presented in June 1984, the “Western” version of the Oltcit, sold under the name Citroën Axel. It was distinguished externally from its Romanian counterpart by a larger and thicker front bumper, side skirts, and a grille bearing the iconic double chevron logo.

Marketed by Citroën in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, and Italy, the Axel was sold in three versions: “standard,” 1 IR, and 12 TRS, all equipped with the GS’s flat-four engine. The Axel was also available in a more utilitarian Enterprise version, lacking a rear seat and with VAT reclaimable.

In Eastern European markets the base version received the two-cylinder engine already used in the Ami 8 and Visa. It would, in fact, disappear fairly quickly from the Craiova production program.

The “top-of-the-range” TRS version, on the other hand, was specific to the Axel and was designed specifically for Western countries. It received the 1,229 cc version of the GS’s four-cylinder engine, which produced 61.5 horsepower, equipped with a five-speed gearbox—an engine not available on its Romanian counterpart. Among a range of more “upscale” equipment, this model featured alloy wheels fitted with Michelin TRX tires. However, this type of tire, with its millimeter-thick profile, was three to four times more expensive than a standard-sized tire.

Fitting the TRX tire to a “low-cost” car was a rather curious choice, bordering on an “aberration.” Especially since these tires, even the AS model, the entry-level version of the TRX family, offered little advantage over conventional tires. This also posed a problem later when Michelin ceased TRX production, as the rims were specifically designed for them and are incompatible with any other type of tire.

Within the Citroën dealer network, however, the reception proved rather lukewarm, not to say downright cold. The model based on the Y prototype was already nearly a decade old design. According to Citroën’s plan, the model should have been launched in 1976. This would undoubtedly have been the case if Peugeot, which had acquired the double-chevron brand two years earlier and hadn’t decided to shelve the project, preferring instead to create, as a cost-saving measure, two hybrid models: the Visa, based on the 104 platform, and the LN (later renamed LNA), a hybrid of the three-door (coupé) version of the 104 with the two-cylinder engine of the Ami 8. During all that time, the automotive market had changed considerably. Expectations and tastes had evolved significantly for a large segment of the customer base. In any case, there was no longer any real room for it within the Citroën range. The Axel, in fact, entered into competition with the 2CV (which, despite its venerable age, still retained a large following), the LN, and especially the Visa.

Though the Visa had a difficult start, thanks to the restyling by Heuliez designers, the introduction of several sporty versions, and some notable rally successes, it found a willing audience.

The Axel suffered from being too similar the Visa aesthetically.

The arrival of its successor, the AX, in 1986, further compounded the problem, making the situation and comparison even more difficult for the Axel.

Add to that the competition, both French and foreign, such as the Peugeot 205, the Renault Supercinq, or the Volkswagen Polo and Golf, to name just the best-selling models on the French market, and the Axel was doomed.

Axel Issues

Articles about the Axel in the French automotive press acknowledged its competitive purchase price and the excellent comfort provided by its suspension, but criticized its excessive noise level, especially at high engine speeds, and its less-than-perfect finish. Like most cars from Eastern Europe, the Axel, in its various versions, was offered at a very attractive price: from 37,000 F

The base model started at 45,000 francs for the TRS version. In comparison, the Visa 11 RE was priced at 48,700 F and the basic LNA, with a 652 cc engine, at 37,860 F. In its campaign Citroën, in its advertising, obviously didn’t hesitate to emphasize this, with slogans such as “For 37,000 F, I’ll give you the maximum!”. However, although the basic version of the Axel was advertised at a price of 37,000 F, even cheaper than the 2CV, price alone was not sufficient to convince customers to take the plunge. Those who, due to lack of resources, looked to Eastern European cars because of their low cost, were more inclined to go with Skodas or Ladas.

Even if the public and the automotive press were unaware that this model originated from Eastern Europe, they would probably have guessed it quickly. Like the great majority of cars from the Eastern Bloc, the Axel suffered from a level of quality and a mechanical reliability notoriously insufficient according to the criteria in force in Western countries.

The engine and gearbox proved to be quite robust and reliable (able to reach the 100,000 km mark without too much difficulty), but the rest of the organs did not hold up as well. A poorly positioned computer that choked the engine had some people experiencing blue smoke spitting out from the exhaust after having traveled barely 10,000 km! Other issues included:

- Peeling paint covering the bodywork

- Chrome parts rusting prematurely

- Plastics (especially the top of the dashboard) cracking or even splitting open completely under sunlight

- Seats sagging

- Brakes which required a lead foot on the pedal to be effective

- Other numerous flaws of all kinds

These defects forced Citroën to implement a “replacement” program aiming to improve, as much as possible, the quality of the cars arriving from Romania. One aspect of the replacement program was to change out Victoria brand tires for Michelin tires as the tires made in Romania, especially ones fitted on base version models, had an unfortunate tendency to burst on the road, when the car was traveling at high speed.

Despite Citroën’s efforts, numerous warranty claims and customer complaints from not only customers but also from dealers resulted in mediocre sales. Barely 6,262 cars registered in France in 1984, in the year of its launch and 7,819 copies sold in 1985, soon resulted in Citroën dealers giving up on the Axel. It would take Citroën three years longer to shed it.

Oltcit Arrears

From 1986 onwards, Oltcit began to experience serious difficulties in paying the French manufacturer for the parts produced in France essential for the production of the Axel. Romanian management then decided to turn to Dacia for mechanical parts (particularly gearboxes and braking systems) to equip part of their production. Only cars destined for the Romanian market would receive these Dacia-sourced components; parts from Citroën would be reserved for models sold in Western markets. But did they adhere to that policy on the assembly line? The Romanian managers of Oltcit’s decision to use Romanian-made mechanical components (from the Dacia 1300) was done so without informing their colleagues at Citroën. It was felt that informing Citroën executives about the change in the supply of components for the production of its models was bound to provoke their anger, however Citroën eventually uncovered the scheme.

Finally, when, at the end of 1988, Ceausescu decided to make the Craiova factory autonomous, and therefore to stop importing parts from France. This, after all the problems and commercial setbacks suffered by the Axel in France and other Western countries, was the final straw. Citroën took the opportunity to terminate the contract and get rid of a model that had become a burden.

Citroën sold its shares in Oltcit to the Romanian state.

Given its short and inglorious career in the Western market, the modifications (mechanical and aesthetic) that the Axel underwent in barely six years could be counted, practically speaking, on one hand. The most notable change was the grille, which was black on the early models and received a new, more prominent design becoming gray from July 1986 onward.

In total, just over 60,000 Axel models were sold in Western European countries, with only 28,115 sold in France. Citroën needed nearly two more years to clear its remaining stock, notably with the help of André Chardonnet’s network; the last 11 remaining examples were not sold until 1990.

In Romania, the brutal fall of Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorship, with him and his wide Elena convicted of charges including genocide and subversion of state power during the Romanian Revolution resulted in them being executed on Christmas Day 1989 following a brief and predetermined trial by a military tribunal in Târgoviște. As symbolic as it was bloody, it echoed the collapse of similar regimes in the Eastern Bloc countries. The decline of Romania’s industry affected Oltcit with the company and its factory in Craiova privatized in 1991 and renamed Automobile Craiova S.A. The Oltcit model was also renamed Oltena after the company’s break with Citroën.

The rapid and unorganized transition from a “pure and simple” Stalinist communist regime to a capitalist system, similar to that of Western countries, quickly led to anarchy and a deep economic crisis for Romania. In the early 1990s, perhaps even more so than under Ceausescu’s rule, buying a new car, however small, economical, and simple, was certainly far from being a priority for the vast majority of Romanians. In order to maintain production at an “acceptable” level, the management of the new company Craiova S.A. decided to focus on exports, marketing and exporting the Oltcit/Oltena to as many countries as possible worldwide.

The Oltena was thus seen in countries as diverse as Uruguay, Egypt, and even China, allowing production to remain around 12,000 units. Although they now “officially” had nothing to do with Citroën, some of the cars destined for foreign markets, particularly those sold in China, received a grille bearing the double chevron emblem. This was probably to “liquidate” stocks of parts originally intended for the Citroën Axel before the end of all collaborations.

Oltcit Prototypes

There was a project for a four-door version of the Oltcit. Two different prototypes of a four-door were developed. The first was built on a chassis with an extended wheelbase, retaining, apart from the doors and roof, all the other body panels of the original three-door version).

The second prototype simply used the original Oltcit platform, without changing the wheelbase. Presented at the Bucharest Fair in 1989, it was hastily built to participate in the event and only completed the day before the inauguration.

While the four-door version project never progressed beyond the prototype stage, a commercial vehicle version project did go into series production. Studied as early as 1988 by the Craiova design office, the initial plan was to create two commercial versions based on the Oltcit: a panel van and a pickup truck. Given budget constraints, the design team revised their ambitions and settled for a single version, based on the original short-wheelbase model. Only the pickup truck with a payload capacity of up to 650 kg, which could optionally be equipped with a polyester resin body to protect its cargo from the elements, was marketed in 1993.

Oltcit Convertibles

Among all the projects and other “special edition” derivatives developed on the basis of the Oltcit, the most “prestigious” or the most “exclusive” was undoubtedly the convertible built in two unique examples and intended to accommodate Presidents Mitterrand and Ceausescu, and their respective wives, during the inauguration ceremony of the Craiova factory.

Due to delays in the factory’s construction, the ceremony never took place. These two exclusive convertibles were never used, though one of them was displayed for a long time in the factory’s main hall.

These cars, painted in a specific metallic gray, were crafted with great care. They featured beige leather upholstery covering the door panels, driver’s seat, rear bench seat, tonneau cover, and chrome brackets on the front fenders to hold the French and Romanian flags during the inauguration ceremony. To facilitate access to the rear seats for dignitaries, the front passenger seat was removed.

The Craiova design office never seriously considered mass-producing the convertible, as tests showed that the structure of these two vehicles suffered from a critical lack of rigidity (undoubtedly due, in large part, to the absence of a roll bar). Following the completion of these two “celebrity” convertibles, a third convertible, painted black and fitted with simpler fabric upholstery, was also produced. It is unknown, however, whether this was at the request of Ceausescu himself or solely on the initiative of the design office. In any case, this third and final example appears to be the only one that survives today.

However, of all the projects, successful or not, developed based on the Oltcit, the most unexpected or “utopian” is certainly that of an American version. The project to market the Oltcit in North American markets was studied by the management of the Craiova plant. The model was to be distributed there through the Chrysler group’s network. The design office drew up plans for modifications to adapt the car to the standards in force in the USA, particularly with regard to safety equipment for resistance to frontal and side impacts. The bodywork, according to the sketches we know of this project, would have received two pairs of circular headlights, replacing the original rectangular ones (again, to comply with local regulations), side marker lights on the front and rear fenders, and large bumpers extending onto the sides and concealing the impact-absorbing devices (another requirement of US standards).

While all this work took place during the presence of Citroën representatives in Romania, it was carried out without their approval and even without them being (at least officially) informed, as this project was initiated solely by the Romanian management of Oltcit, in direct contact with Chrysler executives.

The project was most likely abandoned not for political reasons, but because despite the efforts of Romanian engineers to adapt the vehicle to market demands, and even with the adaptation of an injection system and a catalytic converter, the vehicle did not meet pollution emission standards.

Surprisingly, some tuners and professionals were interested in the Oltcit and more specifically, its Western cousin, the Citroën Axel. Notably, the famous Swiss coachbuilder and tuner Franco Sbarro presented a prototype called Onyx at the 1984 Geneva Motor Show. Sharing the Axel’s doors and hood, in addition to its platform the Onyx design differed significantly, resembling a kind of minivan that could carry up to seven people, with two jump seats facing each other in the trunk.

Among the other versions of the Oltcit studied by the Craiova factory was a project for an economy version, more fuel-efficient than the Club version intended to replace the two-cylinder Oltcit Special, whose production ceased in 1990. This new version was equipped with a diesel engine and a front axle borrowed from the Renault 5. Alas, this one too, was never marketed.

Acquisition by Daewoo, revival of the factory with Ford

Finally, in October 1994, the South Korean group Daewoo became the majority shareholder of the company, which was then renamed Rodae (for Romanian Daewoo).

The following year, the final evolution of the Oltcit was presented, bearing the company’s new name. This version differed from previous Oltena models, as well as the original Oltcit, by its massive front bumper, which, like the redesigned grille, new side skirts, and rear bumper, was now painted the same color as the body. This final model was developed based on a study conducted by the German tuner Irmscher, known particularly for its work at Opel. However, this new and final version of the Oltcit had a short lifespan of barely a year before the new Korean owners decided to definitively cease production of the Oltcit/Oltena.

In total, approximately 217,000 Oltcits (all versions combined) were produced during their fourteen years of existence, between 1982 and 1996, half of which were sold in Romania.

The Daewoo Tico, Cielo, and Espero replaced the Oltcit and Oltena on the production lines at the Craiova plant. The following year, to complete its operations in Romania and ensure the supply of the Craiova site, another plant was opened, manufacturing mechanical components such as engines and transmissions.

From 2001, the Matiz and Nubira II also entered production at the Craiova site.

Even though Daewoo’s models proved to be far more modern (both technically and aesthetically) than the old Oltcit and Oltena, due to a lack of real investment from both the Romanian state during the communist era and the Korean buyer, the factory facilities quickly became outdated and obsolete. It is primarily for this reason that its production remained almost exclusively reserved for the local market.

In 2002, the Korean group, facing serious financial difficulties, was forced to sell its automotive division to General Motors

In 2006, the Romanian government bought back the site, acquiring more than 72% of the capital (for $60 million). This “re-nationalization,” however, was only a temporary process, a way for the Romanian state to find a new buyer. A call for tenders was launched, but candidates were few and far between. Ford was the only manufacturer to express interest in the plant in July 2007.

Before the war, Ford had produced cars and trucks at a factory in the Floreasca district of Bucharest.

The purchase was finalized the following year, allowing Ford to re-establish itself in Romania after a 72-year absence. After a major overhaul, the Craiova plant now produces the Transit Connect minivan and the B-Max minivan for Eastern European countries.