Why does Citroën evoke such strong feelings?

by Per Ahlstrom…..

How can so many people have such set opinions on what constitutes “A Real Citroën”? And why do they feel so strongly about it?

What is “A Real Citroën?

Is the Citroën Type A a real Citroën? The 10 hp Type A from 1919 was definitely “A Real Citroën,” but it is definitely not “A Real Citroën” in the sense that the epithet is used today.

The Type A was not the least unconventional. It was a thoroughly conventional and straightforward design.

In the beginning of Citroën car manufacturing the Citroën innovations were in other areas than the design of the cars. André Citroën modeled his business on Henry Ford’s. Just as Ford had put America on wheels by mass producing a simple car that could be sold at a very low price, Citroën wanted to put Europe on wheels the same way. His contacts with Ford were already established, as Citroën visited Ford before WWI to study his mass production methods. (It is unclear if he really met Henry Ford in person at that time.) And during WWI Citroën used the Ford mass production concept to produce grenades for the French army, thus making a major contribution to the French defense.

The Citroën Type A, was met with great enthusiasm. It was sold at a very low price, 7250 francs, fully equipped with lights and tires. The price was actually lower than the production costs, revealing one of André Citroën’s weaknesses: He was often overly optimistic. This was far below the price of other French cars and even before the car was shown to the public Citroën received 16,000 enquires.

What possibly could be seen as unique in the design of the Type A, was that it had the steering wheel on the left, which was unusual on French cars at this time. The biggest novelty was that the car was built according to the Ford assembly line principles, that it was built for a mass market and that it came fully equipped with bodywork, electrical system and tires from the factory.

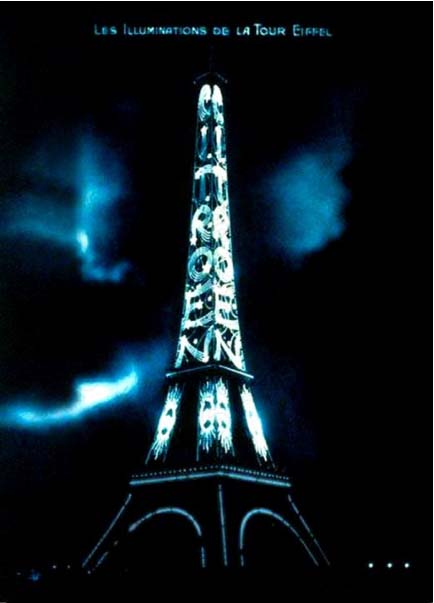

Citroën’s success as a mass producer of cars was not only due to his borrowing of production methods from Ford. He was also a genius of marketing. A few examples: All towns in France and Belgium were offered free road signs – with the Citroën logo prominently displayed of course. And André Citroën still holds the world record in illuminated advertising after he used the Eiffel Tower as a brightly lit advertising billboard for his company for ten years.

He got lots of free publicity through different kinds of events. E.g. when Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris after his solo flight over the Atlantic, Citroën arranged a welcome dinner with 3000 guests in his Quai de Javel factory. It almost looked as if Lindbergh had made his flight just to pay a visit to Citroën – not least because he had been guided to Paris by Citroën’s illumination of the Eiffel Tower.

Citroën also arranged adventure expeditions with his cars. These expeditions used halftrack trucks designed by Adolphe Kegresse, which took them through Africa, Asia and the Canadian expanses of snow. The “raids” still inspire Citroën enthusiasts, above all the 2CV crowd, to make long distance adventurous expeditions.

A more important contribution to the history of automobiles was that Citroën invented the profitable aftermarket. While owners of other cars had to go to the village blacksmith or some generally competent mechanic, the Citroën owner could go to an authorized Citroën garage and have his or her car repaired according to a fixed price list. An observant traveler in France can still see garages that were built in the 1920s according to Citroën’s standard drawings.

It is unclear how much of a technician André Citroën was himself. It seems as if his foremost talents were in other areas, PR and marketing, but his most important talents might have been to understand the needs of his customer base and that he was open to new ideas.

As early as 1924 Citroën introduced an all steel body – lighter, stiffer and quieter than the conventional composite bodies, which had steel sheets nailed onto a wooden frame. The presses were American and the design principles came from Edward G. Budd Mfg. Co in Philadelphia.

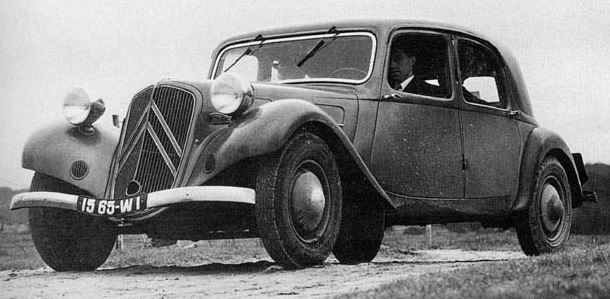

The all steel technology was a necessity for the development of the car which came to define what a “Real Citroën” is, a car that is so different from conventional car designs that the public and motor journalists see it as “weird.” This car was of course the Traction Avant.

When the Traction Avant was launched in 1934 it truly was “weird” compared to other cars. While other car manufacturers still held on to the “Systeme Panhard” from 1892, with separate chassis and bodies, the engine up front, the gearbox in the middle and driving rear wheels, the Traction Avant had the gearbox up front, driving the front wheels, the engine turned backwards and placed behind the driving wheels. The car had no chassis frame and had something truly weird for the time – a unit body. The at this time so common steel bar between the front wheels was lacking, as the Traction Avant had independent suspension for the front wheels, with torsion bar springs and double wishbones. Almost like a modern racing car. The rear was also suspended on torsion bars and the rear axle was what a Swedish innovative car manufacturer forty years later dubbed a “semi stiff rear axle”.

The engine was a state-of-the-art design with overhead valves, but not extreme or truly unusual in any way.

The design as a whole was something the world had never seen before: A mass produced front wheel drive car with road-holding that was superior to everything else.

The Citroën Traction Avant was way ahead of its time, in so many ways.

The Citroën lineup for 1935 listed 20 different models of Traction Avant. From the small 7B with a 1500 cc engine, over the B11 with 1911 cc and bigger bodies, to the 22CV with a 3.8 liter engine. But the B22 never reached the market.

This broad range of models was made possible by advanced “platform” thinking, a way of thinking that eventually was adopted by all other car manufacturers. (One might note that in the 1980s Volvo had three separate product lines with practically no parts in common.)

The ambitious model lineup was another sign of André Citroën’s weakness – the risk taking, the over optimism and the conviction that all his projects would succeed. But on the other hand: Citroën’s dependence on creditors for his huge investments in the mass production machinery and in the all new 1929 models, combined with the new French import tariffs implemented in 1929, the depression that hit in 1930 and cut Citroën’s sales from over 100,000 in 1929 to around 60,000 in 1930, threw all calculations out the window. Citroën had to take a big chance to survive. The choice he had was between a slow death or a radical change that at least had the possibility of pulling his company out of the financial crises.

The Traction Avant is a fantastic collector object, because studying the history of the Traction Avant has so many fascinating aspects.

The history of the Traction Avant is of course inspiring for everyone interested in automotive technology and innovations. But it is also interesting for those who study leadership, group dynamics and not least – for students of marketing and business economy.

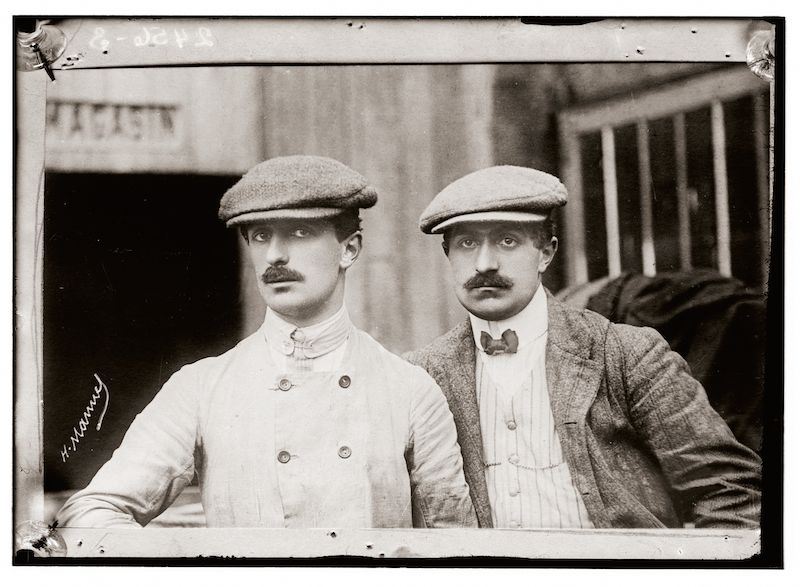

Let us first take a look at the history of Traction Avant technology. It actually starts in the very early days of aviation, with the aviation pioneers Gabriel and Charles Voisin.

The Voisin brothers started selling airplanes as early as 1907. This was actually the first airplane factory in the world. One of the planes was bought by Henri Farman, who on January 1908 started in his Voisin plane from Issy-les-Molineaux outside Paris, flew at a height of approximately 8 feet in a 3/4 mile path and landed in the same spot he had started from. With this he won a prize from the Aeronautic Club and became the first who could say that he had truly controlled his flight. This was no coincidence, as the Voisin brothers truly understood the forces that affected an airplane and how to build it for it to lift off by its own power and to be controlled in flight. (The Voisin planes were aerodynamically stable, with the center of gravity ahead of the center of aerodynamic pressure, like a dart, while the planes built by the Wright brothers at this time were aerodynamically unstable and very difficult to control.)

The concept of aerodynamic stability is important to the understanding of the design principles behind the Traction Avant, the Citroën DS and the SM.

WWI led to rapid development of airplanes. The Voisin concept was quickly adopted by other airplane manufacturers and Voisin grew to become a major supplier of airplanes to the French defense forces. In 1916 Voisin hired an engineer who came directly from the technical university, André Lefebvre. His first design for Voisin was a four wheel landing gear with brakes. (At this time the landing gear of most other planes consisted of two wheels without brakes under the wings and a tail skid).

Voisin took the young engineer to his heart and dubbed him “my spiritual son”. Voisin was a passionate man when it came to planes, cars and women. We know very little about Lefebvre’s interest in women, but we know he only drank water and champagne. When it came to planes and cars he was as passionate as Voisin. Voisin and his spiritual son had a steady stream of ideas around cars, technology and new designs flowing throughout the decades, ending only when André Lefebvre suffered a stroke in 1957 and was forced to stop working.

Voisin taught Lefebvre to not look at what other designers had done. He was taught to go back to basics, to the laws of physics in relation to the design purpose, when he started a new project. And he learned that vehicle performance should be achieved by building light and aerodynamic cars, not by just increasing the size of existing designs. Voisin actually despised the race cars of the day, which (with the exception of Bugatti) were big and heavy cars of almost primitive and brutal design.

Voisin tried to prove his theories by entering competitions with standard engines and standard chassis dressed in aerodynamic bodies. Lefebvre participated in these efforts both as a designer and as a driver.

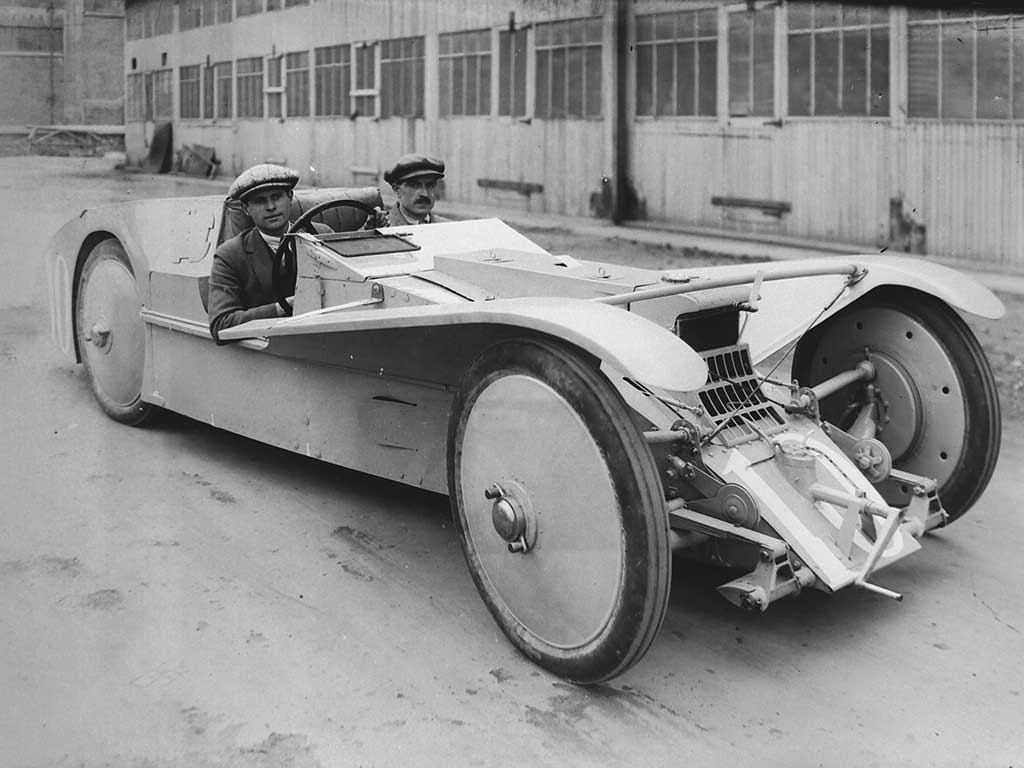

Voisin was successful in competitions in the early 1920s. He developed the sleeve valve engines to a high degree of efficiency, and combined with his way of thinking airplanes when he was building cars – low weight, streamlining and aerodynamical stability – he won many races. Much due to the light weight and aerodynamic shapes of the cars. Others considered this as cheating(!). The rules were changed for the 1923 GP in Tours, so that only boxy bodies were allowed in the touring class. Voisin was enraged, that he put an extremely streamlined body, for the time, on a standard chassis and entered the car in the racing class. André Lefebvre managed to steer the car to a fifth place. It was Lefebvre’s best result in a major race, but an ignorant public saw it as a failure. They gave no weight to the fact that Lefebvre’s car only had 60 hp, compared to the 102 hp of the winning Sunbeam, that the Sunbeam only was 19% faster than the Voisin in spite of having 57% higher hp.

1924 Voisin tried to prove his theses on the race tracks with a new car, the “Laboratorie”. André Lefebvre again was both designing and driving. Everything they could think of had been done to save weight and power. The belt driven water pump was substituted with a water pump driven by a propeller that utilized the wind created by the speed of the car. The track in the rear was diminished to such a degree that a differential was superfluous, etc. It was a great example of how the designers went back to the laws of physics to achieve the desired result – a philosophy that later came to characterize the designs Lefebvre made for Citroën. The narrow rear track of the Laboratory might have inspired Lefebvre in the design of the DS, which also has a narrower track in the rear than in the front. Who said the track has to be the same front and rear?

Voisin was not as good a businessman as he was a technician and in the beginning of the 1930s he could no longer afford to keep his “spiritual son” in his employ. Lefebvre had to find a new job and ended up with Renault. The only outcome we know of from his stint with Renault is that he had a major disagreement with Louis Renault.

At this time Citroën had started work on a front wheel drive car. Exactly how this came about is not documented. And as the Citroën archives were damaged by bombs during WWII we will probably never know. A good guess is that Georges-Marie Haardt discussed front wheel drive with Joseph Ledwinka and other Budd engineers, when he visited Budd in 1930 tasked with finding ways to reduce the weight of the Citroën cars, and thus reduce the cost of imported material. One of the most efficient ways of saving weight is to build a front wheel drive car with a unit body, which is what Ledwinka had in the works. That car was shown to the public in 1931. It so happens that André Citroën visited Budd in 1931, and after this visit he started a frantic effort to develop the new front wheel drive car and rebuild the factory to make production of the new car as efficient as possible.

Jean Daninos, who later started his own brand Facel-Vega, has told that he and his colleagues in the design department one day in 1932 were called to André Citroën, who showed them an Adler Trumpf, which by the way had a chassis and body design from Budd’s German subsidiary, Ambi-Budd in Berlin. He had been offered the rights to produce the Adler Trumpf in France, but he wanted to have a car designed by his Citroën staff. One should note here that the Adler was not well suited to mass production. Its body had too many small parts and too many welds to be economical for Citroën.

But when Citroën described to his engineers what he wanted, they were very skeptical, to say the least.

Citroën told them that he wanted a car that engineering-wise was at least five years ahead of the competition. It should have a marching speed of 90 km/h (55 mph), have a gas milage of 0.9 l per 10 km (26 mpg) and have an automatic gearbox. And: “In the future Citroën customers will sit down into their cars rather than climb up in them as if they are stage coach passengers.”

No wonder the engineers were shaking their heads.

But André Citroën insisted. His chief engineer Maurice Broglie was named project manager of the Project PV (Petit Voiture, small car). A dedicated office was set up in the old Mors factory in Rue du Theatre. The Citroën veteran Maurice Sainturat was responsible for the engine design. Maurice Julien was tasked with developing the novel torsion bar suspension. Raoul Cuinet, assisted by Jean Daninos and Pierre Franchiset were given the responsibility of developing the unit body, which was based on technology developed by Joseph Ledwinka of Budd Mfg in Philadelphia. But Budd managers have clearly stated that the design of the Traction Avant was a totally French affair.

Jean-Albert Gregoire, freelance designer and front wheel drive pioneer, was contracted to deliver drive axles with universal joints for the fwd. The Italian sculptor Flaminio Bertoni was hired to design the body of the new car.

The automatic gearbox was to be designed by Dimitri Sensaud de Lavaud, a wealthy amateur engineer and inventor.

It was a brilliant team. And the overly optimistic André Citroën told them that the new car had to be ready for marketing to the public only two years later.

It turned out to be impossible. The design team quickly fell behind schedule. Here Voisin comes in as a savior. Citroën asked him if he could suggest someone that could help with the new fwd car. Voisin suggested that he hire André Lefebvre, who had assisted Voisin in the design of a fwd car in 1929 – a car that unfortunately has disappeared without a trace.

André Lefebvre left Renault and walked through the Citroën doors in the spring of 1933. Only nine months later Lefebvre could show a driving prototype.

But a driving prototype is not the same thing as a finished car design. The automatic gearbox was the biggest problem. It is said that Lefebvre told Citroën that the automatic gearbox was “excellent for making pommes frites, but useless as a gearbox.” The design had worked in other cars, but in the Traction the gear box oil was boiling when driving up hills. Finally, André Citroën accepted a stop gap solution. Lefebvre was told to design a conventional gearbox that used the casing made for the de Lavaud gearbox. This because 100,000 gearbox cases had already been ordered and were in production. The new gearbox was designed in three weeks, with remote control by a lever on the dashboard via links that quickly were named the Lefebvre Eiffel Tower.

The fact that this provisional gearbox was unchanged throughout the 23 years of Traction Avant production says something about why Citroën time after time have had problems in the marketplace. Even after André Citroën himself had to leave the management of the company to others, the Citroën managers seem to have had more interest in designing novelties than finely tuning and finishing the cars that were in production. This is why Citroëns have this strange mix of old provisional solutions and groundbreaking new designs that were way ahead of their time.

Perhaps it also says something about André Lefebvre’s position in the company, Many of his colleagues bear witness to his loss of interest as soon as he saw that one of his designs worked. At that point he wanted to go on and test new ideas.

It seemed trivial to improve the Traction gearbox when you were working on light alloy wheels and plastic bumpers for the Traction (1934) or trying to convince the Citroën management to build a car with a transverse engine (1937). Lefebvre failed in these efforts and he had to wait 22 years to see his idea of a transverse engine with front wheel drive become reality – not at Citroën but at British Austin/Morris. He is reported to have been very upset when Alec Issigonis showed the Mini in 1959. (In 1959 Lefebvre had difficulties to communicate due to the stroke he had suffered in 1957).

Dire financials, André Citroën’s (by necessity) overly optimistic schedule and Lefebvre’s lack of interest in finalizing his designs was an unfortunate combination. The sales of the Traction Avant started before the car was ready for production. The customers became test drivers and the Traction Avant was almost killed by all the problems the customers had, in particular the problems with the universal joints in the driveshafts.

In the middle of it all Automobiles Citroën went bankrupt and the company was taken over by its biggest creditor, Michelin.

It is a wonder that the Traction Avant and Automobiles Citroën survived this crises. But the new owners had the financial strength and the technical knowhow to sort out the problems at Citroën. They continued to lead the company in the spirit of André Citroën and were open to new and unconventional solutions. They let André Lefebvre continue to develop new and radical ideas and even encouraged him and his team to think differently.

Lefebvre continued to work in the same way as he did with the Traction Avant, with a number of other projects. Three of which have, just like the Traction Avant, become symbols of France and which are also brilliant showpieces for innovative thinking.

They are:

- the 2CV

- the HY

- the DS

All three are subjects for many studies and many books. All three are milestones in automotive history. And they were all designed under the leadership of André Lefebvre.

This is fascinating to those who study leadership and group dynamics, as André Lefebvre never had a formal manager position in the Citroën development department. He never signed off on expenses. He didn’t hire and fire staff. According to his staff he was a leader not by title but by his natural authority and his creativity only. Those who could not keep up with the flow of new ideas and quickly understood Lefebvre’s thinking, didn’t stay long. Those who thought like Lefebvre and told him both yes and no and could explain why, loved their work and stayed on for decades.

Citroën obviously had a management that understood how to handle an extremely creative and odd personality, a person who was obsessed with technology and development, while being totally uninterested in status and career planning.

And the company was paid back many times over by Lefebvre. Even if many Citroën dealers must have been relieved that many of his and his successor’s ideas stayed on the drawing board or prototype stage.

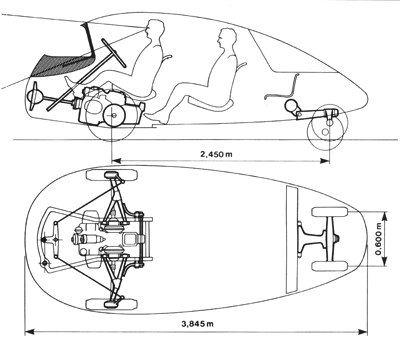

It probably would not have been easy to sell “The Coccinelle” (the lady bug). It was designed to carry six people at 100 km/t, 62 mph, driven by a small air-cooled 2 cylinder boxer engine from the 2CV. Extreme streamlining and extremely low weight was supposed to work wonders.

And it would certainly have been even more difficult to sell “Le Mouton a Cinque Pattes,” a mid-engine car with five wheels, two “normal” wheels, one on each side in the center of the car, and three caster wheels, two up front and one in the back that prevented the car from tipping over. The “normal” wheels were driving the car, and it was steered by varying the relative speed of the driving wheels, like the tracks on a tank.” . Dealers who found it difficult to service the DS must have been happy that Lefebvre and his hydraulics experts, Paul Magés, could not convince the Citroën management to have also the window regulators and windshield wipers hydraulically driven.

The rhomboid high speed vehicle, “The Cat with Five Paws” that was researched in the 1960s, would certainly have made both dealers and buyers confounded. It had two big driving wheels in the center and two caster wheels up front and one in the back. It steered by changing the speed of the driving wheels relative to each other, like the tracks on a tank. This wild project was killed when the French government put speed limits on the autoroutes.

For those interested in management, it is also rewarding to study how well Automobiles Citroën was doing while the creative and entrepreneurial André Citroën had the organizer and realist Georges-Marie Haardt at his side. The pair led Citroën through a very successful 1920s. But after Georges-Marie Haardt died of pneumonia in 1931 on the way home from a “raid” into China, it only took three years for Automobiles Citroën to go bankrupt.

From this we can learn that while both risk taking and careful consideration are important, you have to work with both daring ventures and cold-hearted calculations.

The managers appointed by Michelin after they took over after the Citroën bankruptcy, Pierre Michelin and Pierre Boulanger, understood the genius of the design team André Citroën had put together. They understood the genius of the Traction Avant and put a lot of resources into righting everything that was wrong. The quality was improved, the lineup was reduced, the production was streamlined and the Traction was in production until 1957.

Boulanger was the man who ordered the development of the 2CV – a car designed to carry a French farming family at a speed of 60 km/h (35 mph) and to carry a basket of eggs across a plowed field without breaking the eggs. The car André Lefebvre designed to meet this design brief, the 2CV, was produced from 1948 to 1992. It was Boulanger who ordered the development of the groundbreaking utility vehicle HY, the first van with front wheel drive, that provided a uniquely low loading height, an immense loading volume and load capacity for it size. And it was Boulanger who ordered the development of the DS, the futuristic car that was produced from 1955 to 1975.

That André Lefebvre’s ideas were propagated at Citroen long after the death of Boulanger in 1950 and after Lefebvre himself was paralyzed by a stroke in 1957, is to a large extent due to the management skills of Pierre Boulanger.

We Citroënists are very grateful to André Citroën, Gabriel Voisin, André Lefebvre, Pierre Boulanger and all the others who made Citroën different. Not only because they created interesting cars, but above all because they have shown us the value of original thinking. That they have shown us that you can come out ahead by being faithful to your goals while constantly questioning the traditional ways of doing things.

We are also grateful that we have the opportunity to learn from their failures. From those we can learn to finish what we are doing before jumping on to the next project, to not be overly optimistic, to make realistic business plans and project schedules.

That Citroën stirs such strong feelings can be attributed to the history told here. Some people always feel challenged by innovation and things that are “different”. And some people are very disappointed when a provocateur adepts to the ways of the majority.

Some of Citroën’s challenging ideas have now become common practice. Front wheel drive and fuel economy are today high on the agenda for most car manufacturers. That the driver should be able to reach all vital buttons without taking his eyes from the road is now standard.

Other brilliant ideas Citroën has had to be given up. The excellent Diravi steering, with its progressive power assist, is gone. The utilitarian philosophy behind the H van is gone.

And now even the hydropneumatic suspension that characterized the big, and some not so big, Citroëns for 60 years is gone.

No wonder it is a brand that evokes strong feelings, and that many Citroën enthusiasts are disappointed in the way the brand has developed lately, producing a range of very conventional cars.

But who knows – the new electric Citroën Ami city vehicle that recently was introduced in France, shows that Citroën still can find unique ways of meeting the future. Again, by going back to basics and figuring out the easiest way to fulfill the design brief without looking at conventional solutions.

We can always hope that future full size Citroëns also can create the unique reaction that so many Citroëns have instilled in people: “What the … is that? Why did they do that? – My God! It is brilliant!”