By Thomas Urban….

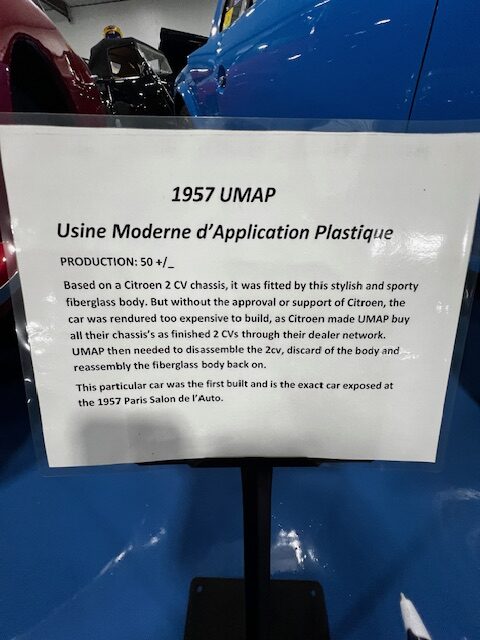

Founded in 1956 by Camille Martin, UMAP (Usine Moderne d’Application Plastique), a company based in Bernon, France, specialized in the artisanal manufacture of special bodies for small manufacturers who wanted to create their own models using mechanical components from mass-produced models as a basis.

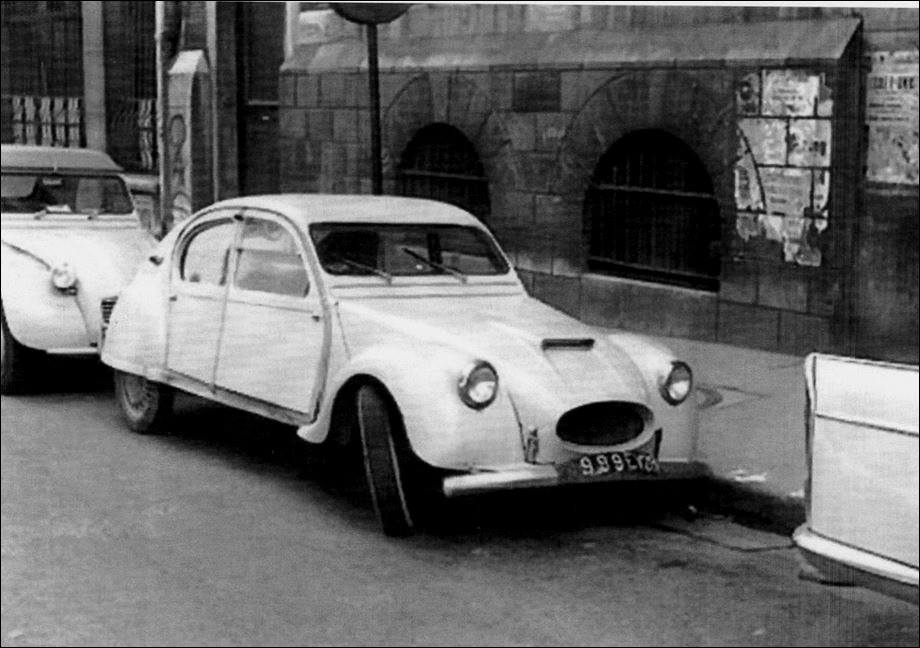

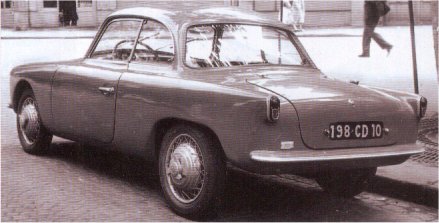

At the 1957 Paris Motor Show, UMAP presented its first creation: a coupé with elegant yet modern lines, whose mechanical architecture was based on the engine and platform of the Citroën 2CV. If it weren’t for the unmistakable double chevron logo, visitors who discovered it while strolling through the aisles of the Grand Palais on the Champs-Élysées (where the Paris Motor Show was held from the early 20th century until the early 1960s) would probably have been unable to guess that its basis came from the modest and hardworking 2CV. This is understandable: when you compare the coupé created by UMAP with the production model from which it inherited the engine and platform, you immediately realize that the two models have completely different purposes.

While the famous “Deux Chevaux” car, presented by Citroën at the Paris Motor Show in October 1948, had the mission (like other new models in the French popular car category, such as Renault’s 4CV) to “put France back on wheels,” no one—whether in the press or the public—used the term “elegant” when referring to its lines; some even considered it downright ugly. It was undoubtedly because its bodywork, in some respects, resembled that of a tin can that one commentator even asked (with undisguised irony) if a can opener came with the car.

Beyond the mockery, and the amused or doubtful glances of the early days, the 2CV nevertheless quickly and easily found its audience catering to many working-class citizens—who, until then, due to limited means, had never been able to access the automotive world. They desired to buy their first car and no longer be dependent on public transportation.

Over time 2CV availability brightened up, notably with a range of body colors that gradually expanded (even including two-tone options), as well as more luxurious versions or limited editions (such as the AZAM Export). However, luxury, elegance, and performance would never truly be part of its DNA, or at least not among its primary characteristics. So much so that, in its early days, given the significant demand that Citroën had underestimated, waiting times reached two or three years.

Several coachbuilders, tuners, and craftsmen, from the beginning of the 1950s, began to take an interest in the 2CV as a working basis for their own creations because it was a popular model produced by a major manufacturer. Low cost acquisition allows it to be built upon and its simple and easy-to-maintain mechanics allowed it to be easily transformed to offer more power.

Most of the popular French cars of the time saw a number of often significant non-series derivatives, whether recreational, utilitarian, or intended for competition. This would be the case for the Simca-Gordini, the Peugeots prepared by Darl’Mat, or even the first Alpines based on the 4CV.

As for the Citroën 2CV, one of the first craftsmen to be interested in it was Jean Dagonet, who developed a version with lowered bodywork and suspension, giving it a much more racy look.

Although at its launch, no one (whether at Citroën or anywhere else) thought of entering it in motor racing, Dagonet was nevertheless one of the first to be convinced that, when duly prepared for this purpose, the “two-legged” vehicle from the Quai de Javel could have good potential in competition and thus shine on the circuits.

Despite its potential, which was quickly recognized by some enthusiasts, the 2CV Dagonet never achieved the success its creator had hoped for, and he ultimately threw in the towel in 1957.

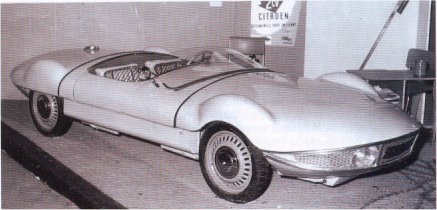

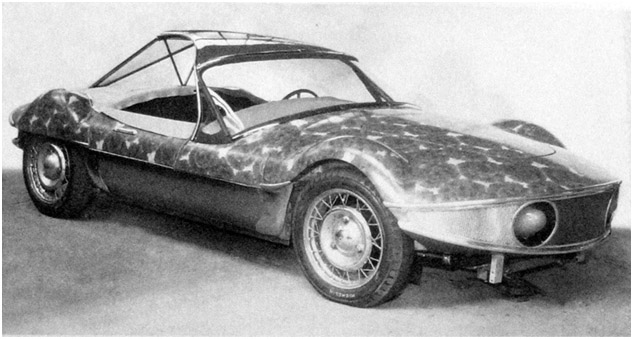

Another of the most original and striking creations based on the 2CV is the Barquette, created in 1955 by the SEPA company at the request of the Marquis Jean de Pontac. This, perhaps more than any other creation based on the 2CV, truly resembles a “UFO” on wheels, with its lines furiously reminiscent of a flying saucer or even a kind of submarine. It generated a lot of commentary (although not all of it was necessarily complimentary) during its first public appearance at the 1956 Paris Motor Show.

It would once again be talked about when it returned the following year, this time with its bodywork covered in a floral print, giving it a fiercely kitsch look that contrasted with the futuristic lines.

Another unique creation based on the platform and mechanics of the 2CV was a superb coupé created by the coachbuilder Antem and designed by the talented stylist Philippe Charbonneaux, who notably worked for the prestigious Delahaye firm in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In the early 1960s, he also worked for Renault, where he designed the characteristic cubic lines of the Renault 8. Unfortunately, this creation remained a one-off.

Among all the non-production derivatives of the 2CV, whether original or more classic, not all of them would win first prizes at elegance competitions. A case in point is the coachwork created by the coachbuilder Clauzet in 1959. Based in the Landes department, he designed a model for the small Citroën with very angular lines, a body made of folded sheet metal, and fitted with a Plexiglas sunroof. With the exception of the round headlights and the four wheels, everything on the 2CV Clauzet gave the impression of having been designed with a ruler and a set square. While it generated much discussion at the time of its presentation, the Clauzet (like other similar designs whose aesthetics were not their main asset) would quickly fall into oblivion.

However, this is only a glimpse of the non-production models based on the Citroën 2CV spanning the period of the 1950s. The projects of all kinds created by coachbuilders and private individuals—varying in talent and inspiration, especially considering the entire career of the 2CV (which spanned over forty years, from 1948 to 1990)—are truly countless, so much so that even the best specialists of the model struggle to compile a completely exhaustive and comprehensive list.

It is, however, interesting, even necessary, to delve into the history of the 2CV Dagonet, because without it, the UMAP coupé might never have seen the light of day. Although he was previously a flour miller in the Reims region, Dagonet soon became interested in mechanics and began his career on the Citroën 2CV. In 1952, he started his first project aimed at transforming the “two-legged” car from the Quai de Javel into a genuine little sports car.

The twin-cylinder engine’s displacement was then increased from 375 to 425 cc, though this did not initially have a major impact on performance, with an increase of only 10 or 15 km/h (raising the maximum speed from 65 to 80 km/h). Even though, in his rework of the 2CV was barely faster than the production model, this did not prevent Dagonet from entering it into competition, eventually achieving notable success, by winning the Bol d’Or Cup in 1954.

Dagonet then started manufacturing and selling a whole range of mechanical components designed to improve the 2CV’s performance, offering drivers (both professional and amateur) the opportunity to build (or have built) a “custom” competition car tailored to the types of competitions in which they wished to excel.

Alongside marketing his sports version of the 2CV, Dagonet developed aluminum cylinders with chrome interiors under the brand name “DAF Chrome” (or Dagonet Faverolles, in reference to the town in Reims where he set up his workshops). He also offered intake and exhaust manifolds, carburetors, as well as single or dual exhausts.

Regarding the aesthetics of the 2CV, Jean Dagonet also added his personal touch. When comparing the transformed model in the Faverolles workshops with its mass-produced cousin at the Javel factory, the differences are immediately obvious. While the overall silhouette remains the same and you can recognize it as a 2CV, there are several differences between the two models. The slant of the windshield and the rear window gives it a much stockier appearance, making it resemble a large insect from certain angles (especially when viewed from the side).

While this first 2CV Dagonet (although its overall style was not unanimously approved) could boast a rather racy style, this description cannot be applied to Jean Dagonet’s second creation based on the 2CV, which was presented at the Paris Motor Show in October 1956. This second creation took the form of a coupé clad in a plastic body, whose style owed nothing to the 2CV. Aesthetically speaking, while the first 2CV created by Dagonet was never truly unanimously accepted, his second creation—based on the platform of the small Citroën—was almost unanimously critiqued negatively.

While Dagonet wasn’t the only designer among those who worked on the 2CV to miss the mark and botch his design (far from it), it must be admitted that, in this case, he seemed to have been particularly heavy-handed, integrating fenders and headlights into a body that, overall, turned out to be quite unsightly. Given this more than questionable result in terms of style, it’s hardly surprising that the Dagonet coupé remained a prototype.

After this new, inconclusive experiment, and considering the commercial failure of his “racing” version of the 2CV, Jean Dagonet finally decided to retire. While he ceased his activities as a manufacturer, he did not lose interest in automobiles or transformation projects (mechanical and/or aesthetic) based on the 2CV. Indeed, with extensive experience in the field, he was soon approached by UMAP, which was simultaneously working on its own special version of the 2CV.

Like Jean Dagonet’s coupé, the one created by Camille Martin also featured a body made entirely of plastic. Since the launch of the first generation of the Chevrolet Corvette four years earlier, manufacturing techniques for synthetic bodies had rapidly developed (whether using polyester or fiberglass). The emergence of these new materials was a boon for many small manufacturers, who could create bodies with any shape while benefiting from significantly lower manufacturing costs than steel or aluminum. This also offered their models two essential advantages for sports cars (or those with a sporty vocation, as most of the models concerned were): lightness and rigidity.

In the case of the UMAP coupé, the bodywork is made of fiberglass. The first step in creating this bodywork involves unrolling rolls of fiberglass and pre-cutting the panels that make it up. Low-pressure molding is then carried out using concrete presses covered with epoxy. For parts of the bodywork that consist of large flat surfaces (such as the hood, doors, fenders, and roof), cast iron presses are used instead. These have the advantage of allowing panels to be removed from the mold with a smoother surface, thus avoiding the “orange peel” effect that would make the bodywork panels appear “unsightly” and would have rendered the surface unsuitable for obtaining a quality paint job, which would have necessitated redoing all the work.

Once the fiberglass panels are placed inside the molds, a “gel coat” is applied to the hollow part of the mold. This product gives the plastic a smooth appearance once the parts have been demolded. Two sheets of fiberglass are then placed at the bottom of the mold (which reproduces, in a hollow form, the shape of the various panels that make up the bodywork). The mold is then pressed for the first time, allowing the fiber to be shaped and heated. The resin is then poured and spread inside the mold over the fiberglass. The mold is closed and remains under pressure throughout the polymerization phase and until the body panels are fully molded and cured. (Another technique for manufacturing fiberglass panels involves injecting the resin into the mold under high pressure rather than molding it at low pressure.)

While most panels and other plastic parts made for the automotive industry are produced from polyester, they can also be molded in other materials, such as polyurethane or SMC (a variant of polyester). Regarding the creation of the UMAP coupé’s lines, while we still don’t know—at least not with certainty—who designed them, specialists who have studied the history of this very special and atypical 2CV attribute it (depending on varying opinions) either to Philippe Charbonneaux or to the coachbuilder Chappe et Gessalin (one of the pioneers of fiberglass bodywork manufacturing in France, which notably provided the bodywork for the first Alpines before becoming a manufacturer itself by marketing small coupés and roadsters with Simca engines under the name CG). It is true that the lines of the UMAP coupé strongly resemble those of the coupé made by Antem based on its design. It is therefore quite possible that Charbonneaux drew inspiration from this prior creation when designing the lines of the UMAP coupé (especially since there are countless examples of “reinterpretation,” “reproduction,” or even “tracing” of previous creations by both French and foreign coachbuilders or stylists, both then and now).

The alternative hypothesis, suggesting that the style of the 2CV UMAP was conceived in the workshops of Chappe et Gessalin, located in Brie-Comte-Robert, is equally plausible because, at the time, the future manufacturer of the CG was already no novice in the design of small sports cars. Before shifting its attention to plastic materials, the Chappe brothers’ company had first resorted to the more traditional technique of metal bodywork, although they favored materials that guaranteed great lightness from the outset.

One of their first creations, on a Talbot chassis, was thus dressed in a duralumin body. In the field of small sports cars, one of their initial achievements was the Monomill single-seater series for the manufacturer Deutsch & Bonnet.

Beginning to take an interest in plastic bodies in the mid-fifties and quickly acquiring recognized expertise in the field, it was therefore quite natural for the Chappe brothers to enter into a partnership with Jean Rédélé when he established the Alpine brand in 1955. For ten years, until 1965, nearly all the bodies intended for Alpine models emerged from the Chappe and Gessalin workshops. It was in the early 1960s, when Albert and Louis Chappe welcomed a new partner into the company, Jean Gessalin, that the idea gradually emerged of no longer being satisfied with manufacturing bodies for other manufacturers and instead producing their own cars.

The decision made some time later by Alpine to cease production of its GT4 coupé (the last Alpine whose bodywork left the Brie-Comte-Robert workshops) and to ensure, from now on, the entire production (including the manufacture of the bodies) within its Dieppe factory ultimately prompted the trio to take the plunge and create their own brand.

CG made its first public appearance at the opening of the Paris Motor Show in October 1966. Although they quickly enjoyed decent success with enthusiasts, the CG adventure lasted less than eight years. Like many other sports car manufacturers, the CG brand was dealt a fatal blow by the outbreak of the oil crisis in the fall of 1973 and the resulting economic recession, forcing it to close its doors in the spring of 1974.

The commercial career of the UMAP 425 coupé (named after its 425 cc engine displacement) was even shorter, with only around fifty to a hundred units produced at most (the exact number, unfortunately, is still unknown today). The reasons for the UMAP coupé’s commercial failure are, especially in hindsight, quite easy to understand. Firstly, its image as a small, prestigious sports car hardly fit in (and was even the antithesis of) that of the simple (even austere) and hardworking little car that was the 2CV. This was especially evident given that the double chevrons on its hood clearly indicated the origin of the mechanics underneath. Its manufacturer never tried to hide the fact that the coupé was built on the basis of a 2CV and even clearly “claimed” this in its advertisements. However, much like most small artisans who sought to embark on the automotive adventure by using engines from popular mass-produced cars—whether Citroën, Peugeot, Renault, Panhard, or Simca—as the mechanical basis for their models, this may have been a mistake. The overly “plebeian” image of its mechanics did not align with that of a prestigious sports car.

On the other hand, the UMAP coupé was listed (like most of its rivals, for that matter) at a price that seemed far too high considering the origins of its mechanics and the “modest” performance (95 then 115 km/h when its engine was increased from 425 to 455 cc, and from 12 to 19 horsepower): 920,000 francs (while a basic 2CV cost barely 390,000 francs). Despite a curb weight of only 500 kg, thanks to its plastic bodywork, the UMAP coupé appeared somewhat underpowered, especially since its lines suggested much superior performance in the eyes of some. For the vast majority of the public or customers who might have been interested, this selling price remained far too high for a car—even a luxury one—equipped with a 2CV engine.

Another factor was that the philosophy and target clientele (that of high-society women) was diametrically opposed to that of the 2CV as Citroën had designed it. Citroën, for its part, refused to support the UMAP’s need to supply it with chassis and engines for the production of the 425 coupé. This forced the Reims company to turn to Dagonet to obtain mechanical parts. The problem was that Dagonet’s prices were far from competitive, and the high cost of the components supplied by him quickly and significantly burdened UMAP’s finances. Like most of the craftsman-manufacturers (mainly in France but also abroad) who created their “chic” version of the 2CV, UMAP, despite the very successful lines of its 425 coupé, failed to secure a place in the automobile market.

Unfortunately for their creators, almost all French creations of the same genre based on the Citroën 2CV would also see their ventures cut short, meeting similar ends. Some would remain prototypes with no future, disappearing without a trace after shining at one or two motor shows.

The resounding failures of creations by Dagonet, De Pontac, Clauzet, Charbonneaux, and UMAP convinced craftsmen-builders and independent designers who remained interested in the small Citroën to either abandon their projects or, in search of alternative models that could serve as mechanical bases, turn to other popular mass-produced French cars. Some chose to redirect their efforts entirely, creating models with a more playful or utilitarian purpose.

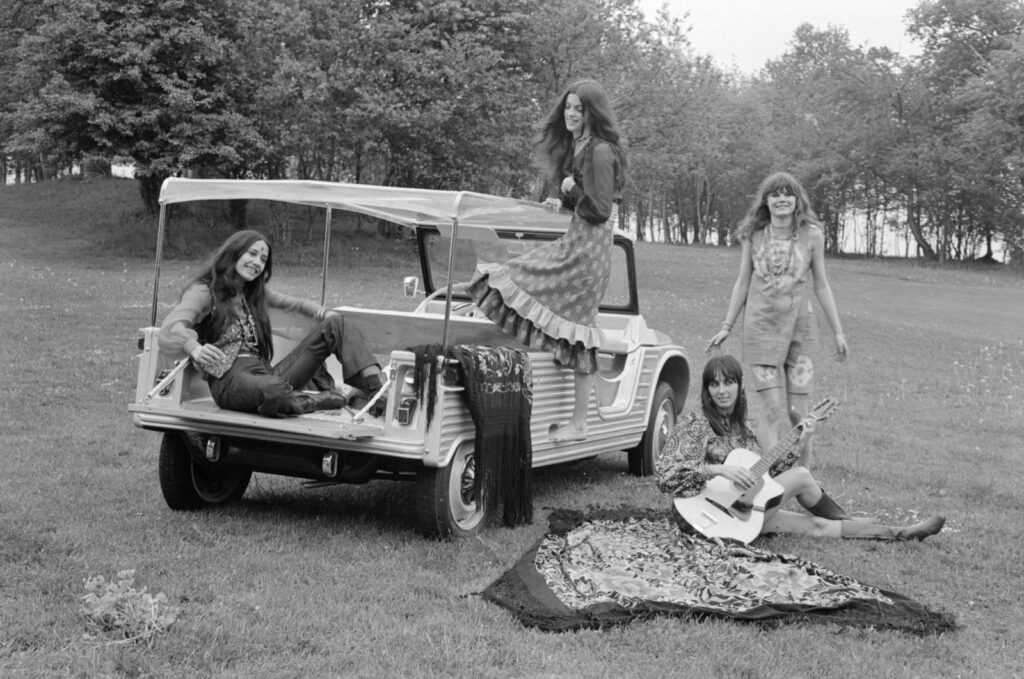

The success of the Méhari, launched by Citroën in 1968 (even if its launch did not initially attract much media attention due to occurring during the riots and strikes of May), showed the way forward.

The vast majority of the special 2CVs created from the end of the sixties were often (more or less) inspired by the Méhari.

If, subsequently, a certain number of creators (varying in talent and inspiration) and sometimes manufacturers opted for “donor cars” deemed more modern and efficient than the 2CV, this did not prevent the 2CV from continuing as a desirable model, retaining both sentimental value and commercial success until the end of its forty-two years of production in 1990.