Dynasphere: The one wheel Car of the Future, but only a few saw the light of day.

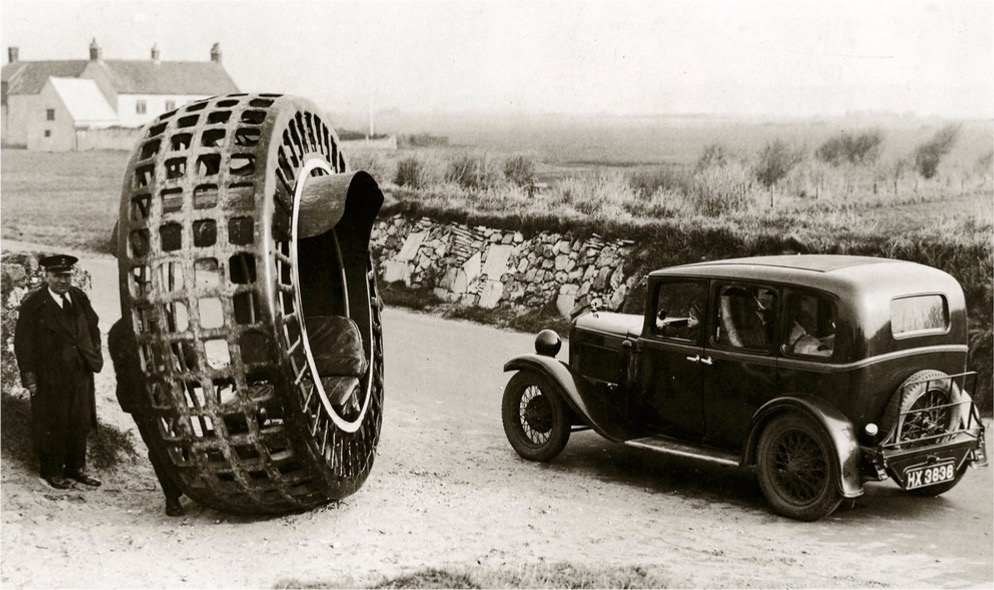

While Citroën was busy in the early 1930s creating the Traction Avant and the TPV (Très Petite Voiture (very small car) that would eventually become the 2CV), one inventor in England was working on an automobile that even Citroën engineers would find weird. Dr. J. H. Purves set out to build the car of the future having just one wheel! That wheel, in fact, was the entire car.

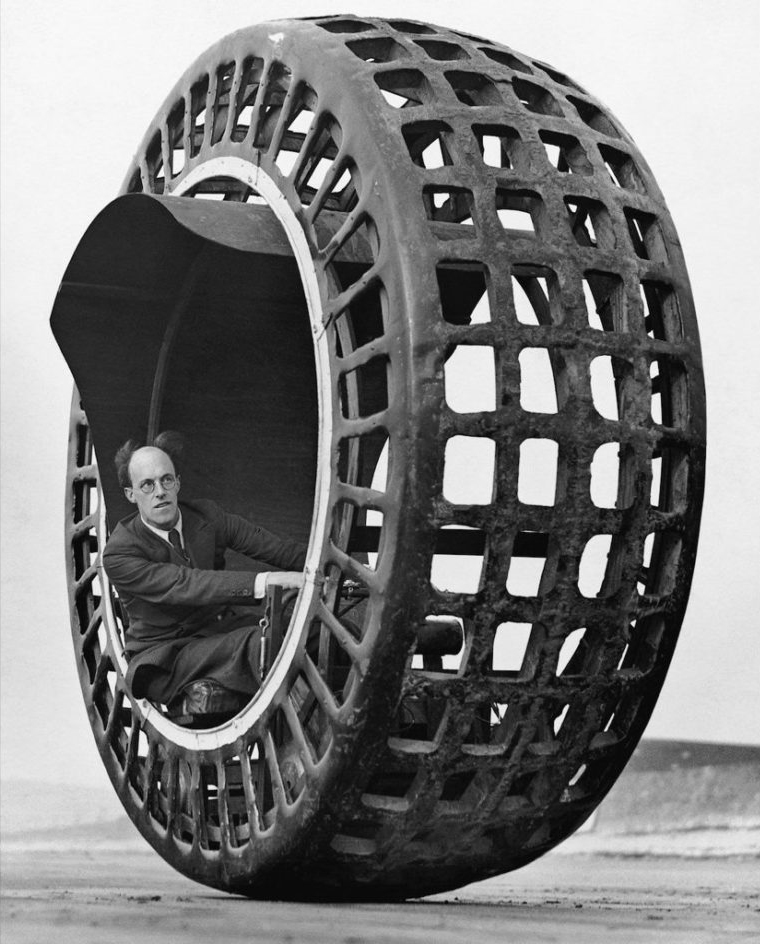

The Dynasphere, as he called it, offered a cabin within the circumference of the wheel for the driver and passenger to sit. The June 1932 issue of Modern Mechanics explained how it worked:

“Inside the wheel, on either side, tracks run completely around. The motor is geared to the track so that, when the engine is started, the motor pulls the track toward it and so starts the wheel in motion. Center of gravity is low to prevent the wheel from tipping over.

The weight of the motor and driver is sufficient to keep them always parallel with the ground—if the driving apparatus were sufficiently light, the motor might conceivably climb up the geared track instead of pulling it and the attached wheel around.

Speeds of thirty miles an hour, with two occupying the seat, have been comfortably attained. The lattice-work in front of the driver’s eyes disappears when the wheel is in motion, flashing past so rapidly that he has a good view of the road he is traveling.”

Purves made at least three prototypes. The larger one featured a gasoline motor capable of 2.5-horsepower — enough to propel the thousand-pound wheel. The smaller prototype ran on electricity. (Purves was a true futurist!)

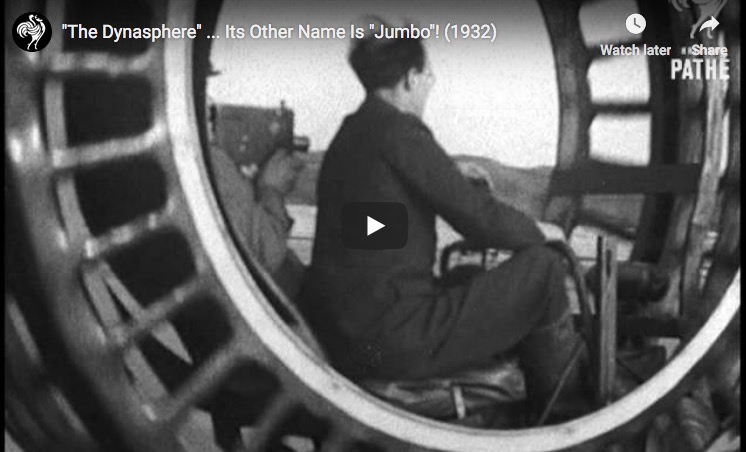

Watch the Dynasphere in action below:

Steering and braking were not its strongest virtues. Nor were forward visibility or the ability to shield its occupants from the elements. Another aspect of the vehicle that received criticism was the phenomenon of “gerbiling”—the tendency when accelerating or braking the vehicle for the independent housing holding the driver within the monowheel to spin within the moving structure.

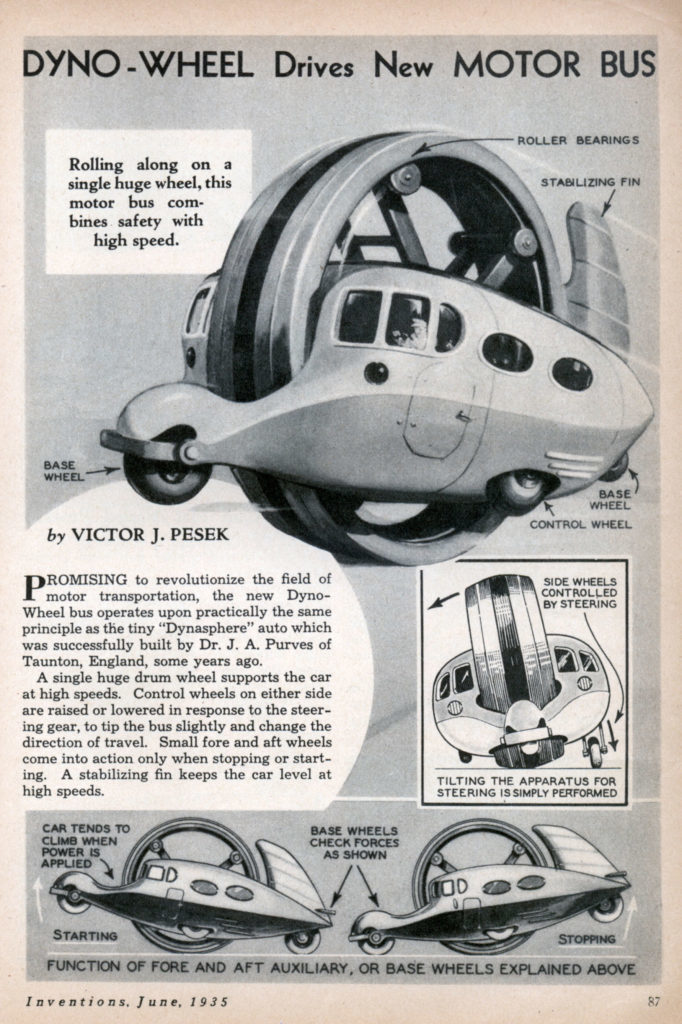

In 1935, Purves developed an enclosed bus version to hold more passengers.

And you thought Citroën designers and engineers at the Bureau d’Etudes were far out in their thinking!

are there any functional Dynasphere today?