Citroën Visa 1000 Pistes – Bodybuilding and Competition

By Thomas Urban….

When the Visa was unveiled to the public in 1978, few— including the automotive press, the general public, and even most of Citroën’s management—believed it had a chance in the competitive market. This skepticism is understandable when considering the model’s origins and early career.

At the time of its debut, although Citroën had been acquired by Peugeot four years earlier, many passionate Citroën enthusiasts had yet to come to terms with the takeover. While the significant restructuring carried out by Peugeot (including the sale of Maserati and the abandonment of Wankel rotary engine projects) allowed Citroën to regain stability fairly quickly, many loyal customers feared that the brand’s cars would lose much of their distinctive personality. This concern stemmed from the cost-cutting measures that might lead to the extensive use of components borrowed from Peugeot models or, in a worst-case scenario, simply rebranding Peugeots with Citroën badges.

Subsequent events did validate some of these fears, particularly regarding models like the LN and LNA, which resulted from combining the body of the Peugeot 104 coupé with the mechanics of the Ami 8. However, the PSA Group—formed following Citroën’s acquisition to separate its activities from Peugeot into two distinct entities—allowed the double-chevron brand to maintain an avant-garde and unique image, both technically and aesthetically. Despite this, pragmatism and budgetary constraints, long-standing pillars of Peugeot’s policy, would soon limit Citroën’s model development program.

One of the first projects affected by these new constraints was Project Y. Intended to replace the Ami 8, it was planned to feature the air-cooled twin-cylinder engine from the Ami 8 in its entry-level version, while higher-end versions would be equipped with the flat four-cylinder engine from the GS.

After Citroën’s acquisition, Project Y was shelved—later emerging to be produced for the Romanian regime under Ceausescu, resulting in the Oltcit, which was marketed in the West as the Citroën Axel.

In its place, a new study was conceived jointly (though likely without much enthusiasm) by Peugeot and Citroën teams: Project VD (for “Reduced Vehicle”; the name itself indicated a lack of enthusiasm among Citroën staff for what they considered a “hybrid” model).

Aesthetically, the Visa, the product of this new project, closely resembled the latest designs from Project Y. However, it adopted the Peugeot 104 platform. While the base versions retained the Ami 8’s mechanical components, as initially planned, the higher-end versions featured the engines from the 104. Consequently, many Citroën enthusiasts felt these models no longer resembled a “true” Citroën, except in name. Although the Visa achieved fairly respectable sales figures, it fell short of the expectations set by Citroën executives.

One of the most criticized aspects of the Visa, both by the automotive press and a significant segment of customers, was the front-end design. Critics deemed it unattractive, with the bumper and protruding grille forming a single, unified nose. The trapezoidal grille strongly evoked a pig’s snout, while the bumper resembled lips artificially inflated, not to mention the headlight design that completed the Visa’s “beaten dog” appearance. Despite aesthetics rarely being a primary factor in purchasing decisions for city cars and subcompacts, Citroën management quickly recognized that an unappealing front design could be a significant handicap if they wanted the Visa to achieve commercial success.

In 1981, Citroën turned to the coachbuilder Heuliez—which already produced the bodies for the brand’s commercial vehicles, as well as the station wagon versions of its passenger cars—to redesign the front end of the Visa. The task was not easy for the Cerizay-based company, as they were instructed not to modify any body panels due to a drastically reduced budget for this facelift. While Heuliez’s work was limited in scope, it was ultimately agreeable in outcome and met Citroën’s expectations, leading to a sharp increase in sales.

Around the same time, in order to boost sales and enhance the model’s image, Citroën decided to offer several sporty versions of the Visa. The first mass-produced sport variant was the front-wheel-drive Visa GT, introduced in 1982. This model was the most powerful Visa yet, featuring a new generation 1,360 cc engine. It had a 90 hp four-cylinder XU engine from the collaboration with Peugeot, with the displacement increased to 1,580 cc. To accommodate the increased power, the Visa GT was fitted with two downdraft single-barrel Weber carburetors (a lower power single-carburetor version was produced for Switzerland). Citroën also needed to rebuild the front end, including new mounting points and suspension components.

While the Visa GT never achieved the same renown as its Peugeot cousins, such as the 205 GTI, Citroën still aspired to take the Visa a step further by successfully homologating it for what was then the most iconic and elite category in 1980s rallying: Group B. This ambition was driven by Guy Verrier, a rally driver turned director of Citroën’s Competition Department.

Various projects and prototypes were studied and developed, including a mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive car created by Citroën’s design office. Other projects were carried out in partnership with different manufacturers and tuners. Alliances were formed with Strakit and Lotus to leverage their expertise, which Citroën lacked in this domain. Entrusting design to Lotus was particularly interesting because the British manufacturer, known for its ultra-lightweight sports cars and tuning activities—including projects on the Ford Cortina and the Talbot Sunbeam—used their Esprit Turbo as a starting point for this project. It is unfortunate that the “Citroën-Lotus” prototype was ultimately abandoned, as its potential in competition was likely high.

However, Citroën’s management preferred a car with a 100% French design, which is hardly surprising given that motorsport—regardless of category—places significant importance on national pride.

Recognizing the benefits they could reap in terms of brand image, Guy Verrier and Citroën executives decided to enter the rally-transformed Visa in the Group B category. This decision likely originated with Verrier, who, despite his charisma and considerable persuasive ability, must have skillfully convinced them that this “Citro-Peugeot” or “Peugeroën”—as ardent Citroën enthusiasts would refer to it, often with irony or disdain—could have a real chance of competing against far more powerful rivals.

In total, four race-prepared Visas competed in the event, driven by Marc Lacaze, Christian Rio, Philippe Wambergue, and Pierre Pagani. The Visa designed by Denis Mathiot and driven by Wambergue, although the least powerful and least developed of the four, was the only one to finish the race, winning in the “experimental” category.

Guy Verrier explained to a journalist from the Auto Moto program before the start of the race that this event would be crucial in determining the future path not only for the Visa in competition but also for other models of the brand that would follow, which would, of course, bear little resemblance to production models. He stated that ultimately, a choice would have to be made between the race for power or the pursuit of weight reduction—creating cars as light and agile as possible so that, combined with the talent of the drivers, they would have a real chance to beat competitors with larger engines. The victory of the Visa developed by Mathiot clearly indicated to Verrier and the Citroën management that the second option was undoubtedly the best.

The Visa Trophée was launched in March 1981 and obtained its Group B homologation in December of the same year. It entered its first competitions early the following year. The car used the 1219 cc XZ engine found in the Visa Super X, but with a heavily modified cylinder head that breathed through two side-draft Weber 40 DCOE carburetors, producing an impressive 100 PS (74 kW). Some rally versions were increased in capacity up to 1299 cc and could produce up to 140 PS (103 kW). The Trophée benefited from weight savings over the GT, utilizing lighter fiberglass body panels and Lexan side windows, allowing it to weigh just under 700 kg.

The Visa Chrono was released in 1982, targeting competition in the larger capacity Group B engine class, similar to the Trophée. It used the same 1360 cc XU engine as the GT but featured a modified, larger valve head and two double-barrel side-draft Solex C35 carburetors, producing 93 PS (68 kW). A total of 2,160 units were produced for the French market, with an additional 1,600 units made for continental Europe outside France. The non-French models were equipped with Weber carburetors instead of Solex and produced 80 PS (59 kW).

Following the success of the Visa Trophée and Chrono, Verrier turned his attention to international motorsport with the introduction of the Visa International Trophy, established the following year with the support of Michelin and Total for both organization and sponsorship. Verrier had no intention of stopping there; he aimed for the culmination of this ambitious program to be nothing less than a challenge in the World Rally Championship (WRC). This formidable task was made all the more difficult by fierce competition. He understood that for Citroën to have a serious chance of reaching the podium, they would need a custom-designed weapon for WRC. This meant, in many respects, starting from scratch and exploring several avenues to discover the most effective approach.

While the Trophée and Chrono demonstrated their potential as “winning machines,” the Competition Department teams and their director quickly realized that significant changes would be necessary to stay competitive. In just a year or two, the competition landscape had shifted dramatically, primarily due to the arrival of a new racing beast: the Audi Quattro Sport. Thanks in part to its shorter wheelbase and even more powerful engines than the standard Quattro (with its long wheelbase), it posed a clear threat to sweep all trophies in its category. The Quattro coupes proved, from their very first competitions, the superiority of all-wheel drive, delivering unparalleled road holding on any terrain.

For Citroën, as well as many other manufacturers competing in rallies at the time, the conclusion was clear: all-wheel drive was the way forward. Guy Verrier appointed three competition specialists—Michel Odinet, Denis Mathiot, and Strakit—to focus on four-wheel-drive development, tasking them with designing their interpretation of what the future Visa should be to dominate Group B.

Michel Odinet revived a rear-engine Visa project that Citroën had studied in 1981, powered by a 1,434 cc supercharged four-cylinder engine developing 160 horsepower. Ultimately, Citroën’s Competition Department selected only the two front-engine all-wheel-drive versions developed by Mathiot and Strakit to race under the brand’s colors during the 1983 season.

Outside of Citroën and Verrier’s direction, other tuners like Laurent Brozzi developed their own, more radical interpretations than those of Mathiot and Strakit. Brozzi drew inspiration from another Citroën model introduced in the late 1950s, the two-engine 2CV Sahara, which was not intended for competition. He installed two engines in the Visa, providing a combined displacement of 2,868 cc and a power output of 180 horsepower.

Another tuner, Henry Dangel, though not selected by the manufacturer, aimed to make the Visa a rally queen. Dangel specialized in transforming Peugeot and Citroën utility vehicles for use by the gendarmerie, firefighters, and forest rangers. He produced a prototype powered by a 2,849 cc mid-engine V6 with two triple carburetors and a 5-speed gearbox from the Peugeot 604 range, capable of handling the torque with 175 horsepower.

Michel Mokrycki also worked independently from Citroën, equipping a Visa with the 2,155 cc Chrysler 4-cylinder engine from the Talbot Tagora, boosting the power to 210 horsepower.

Meanwhile, Guy Verrier and his team at Citroën developed the Visa “Mille Pistes” for the Group B B/10 class. This model was essentially a four-wheel-drive Chrono with the same 1360 cc engine, but with twin Weber 40 DCOE carburetors producing 112 PS (82 kW).

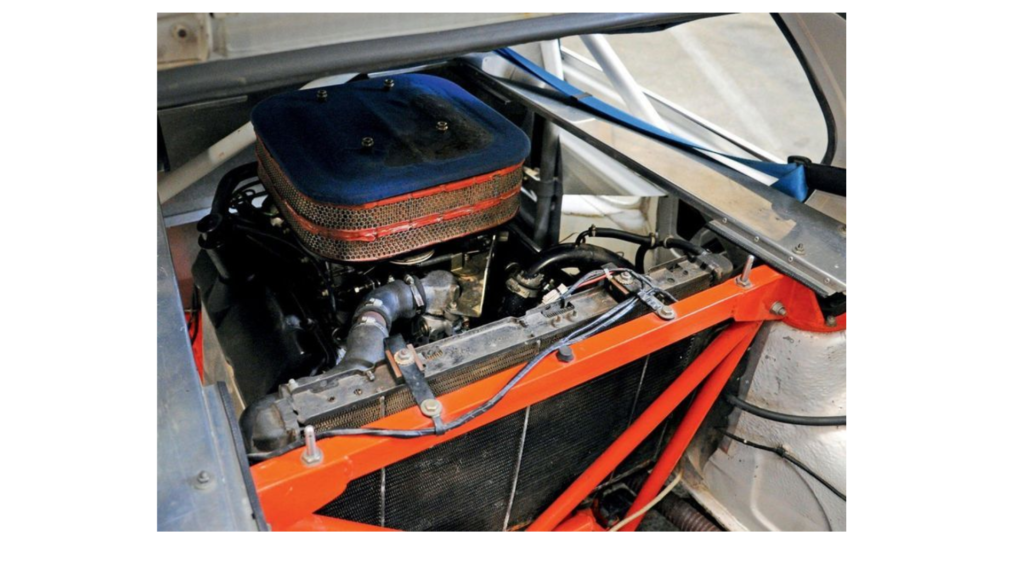

Only 20 units of the competition version of the Visa “Mille Pistes”, named “Evolution”, were produced. Citroën deemed this number sufficient to compete in the main championship events open to Group B cars. The Evolution models were modified by Denis Mathiot; the displacement was increased to 1440 cc, and power ranged from 135 to 140 PS (99 to 103 kW), with a reduced weight of 750 kg (1,653 lb).

As Group B regulations stipulated that models in this category had to be produced in a minimum of 200 road-going versions to receive homologation for competition, Citroën once again turned to Heuliez, which produced all the specific bodywork components. In November 1983, 200 production versions known as the Visa “1000 Pistes 4 x 4” were offered for sale to the public. The name “1000 Pistes” referenced the rally of the same name held on the Conjuers plateau in the Var region in July of that same year, where various prototypes of the new Visa competition cars were entered.

In addition to the Visa, Guy Verrier and his team at Citroën also focused their competition program efforts on another of the manufacturer’s models: the BX. Although the BX in Group B competition form (as those familiar with the history of the BX 4 TV know) would not quite meet expectations. It fell short, to put it mildly.

Of the 200 officially road-legal 1000 Pistes 4 x 4 models, many were purchased with the intent of racing them, as the vast majority of buyers were amateur rally drivers. The primary purpose of the Visa 1000 Pistes 4 x 4 was clearly stated and explained in detail in a letter written by Guy Verrier himself, a copy of which was provided to each buyer:

“Dear Sporting Customer,

You have just taken possession of your Visa 1000 Pistes 4 x 4. You will have the satisfaction of driving the first French four-wheel-drive car designed for competition. As this Visa is intended for competitive use, do not be surprised by the significant noise coming from both the engine and the rear axle. We want to remind you that if you purchased this car for “pleasure driving,” which is not its intended purpose, you should not hold it against us.

With your vehicle, you will only need to add safety accessories that comply with sporting regulations so that you can participate in medium-sized rallies.”

Most buyers, clearly reminded of the intended use of this “Visa in a tracksuit,” did not hesitate to make the necessary modifications, though not all of them possessed the same driving skills as Philippe Wambergue or the other drivers who excelled in races behind the wheel. This resulted in numerous off-road excursions, some of which left the Visa 1000 Pistes and/or its occupants in less than perfect condition. Consequently, of the 200 examples produced, few have remained in their original state.

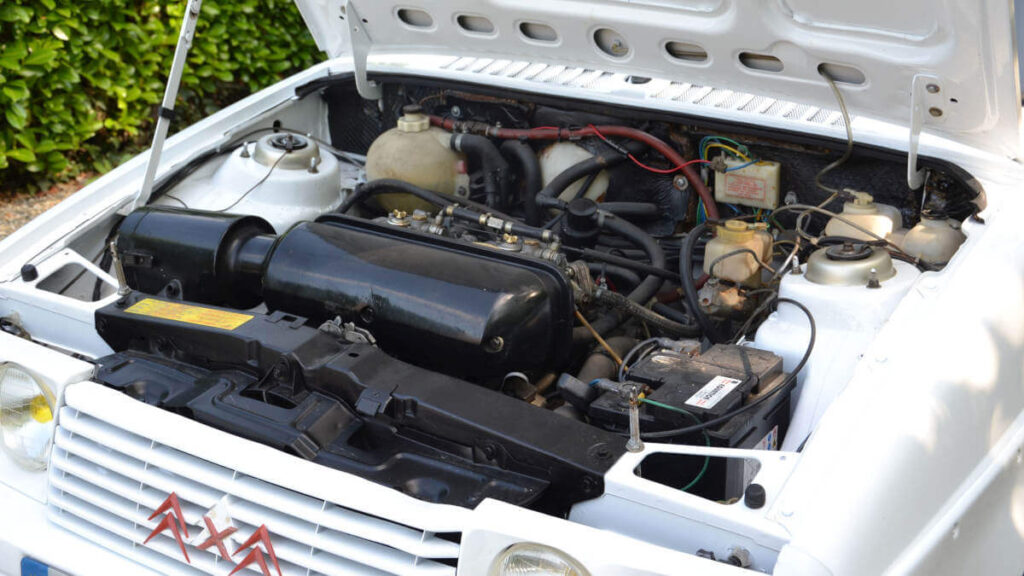

The 1000 Pistes 4 x 4 can be distinguished by its characteristic “white tracksuit.” It was fitted with Michelin TRX tires on Amil wheels, a grille featuring a curious “X” logo framed by two red double chevrons, four round headlights similar to those found on the Visa GTI (supplied by Morette), riveted wheel arch extensions (front and rear), a front spoiler incorporating fog lights, and long blue and red stickers with the inscription “4-wheel drive.” These colors, representing the French flag, combined with the full-body treatment, emphasized the car’s origins and aimed to excite the driving experience. A spoiler on the tailgate at the bottom of the rear window and an exhaust outlet positioned on the right gave the car distinctive rear styling.

Inside the cabin, changes were more limited, with most modifications specific to the 1000 Pistes focusing primarily on the dashboard. The control levers, characteristic of the standard Visa of that era and grouped on the “satellite” located to the left of the driver, were replaced by conventional control stalks on the steering column and dashboard switches. The instrumentation featured Jaeger dials similar to those mounted on the Visa Chrono, although surprisingly, a water temperature gauge was absent.

Most of the gauges providing information about the car’s condition were located directly in front of the driver, while the voltmeter and fuel gauge were placed at the center of the dashboard, to the right of the center air vents—likely due to space constraints. This arrangement made the presence of a co-driver even more useful, if not necessary, to monitor these gauges (especially the fuel tank, as fuel is quickly consumed during rally stages) and to read the logbook.

The seats featured durable black fabric with red trim, similar to those in the Visa GT Tonic. Though reasonably comfortable, they offered little support. Owners often removed the rear bench seat to store it in the garage while replacing the front seats with bucket seats for competition use.

Trunk size was significantly reduced due to the 55-liter fuel tank (which was considerably larger than that on a “standard” Visa) and the spare tire, which was mounted in the engine bay on standard models.

The familiar 1,360 cc XU four-cylinder engine, fed by two Weber 40 DCOE carburetors, allowed the Visa to reach a power output of 112 horsepower at 6,800 rpm. While this may seem modest for a road-going version of a Group B car—especially compared to some models in the same category, like the Audi Quattro Sport, which reached or exceeded 300 horsepower—the Visa’s weight of just 878 kg (1,000 lbs) provided respectable performance for its class. Additionally, the Visa’s front/rear disengagement system allowed it to be driven in front-wheel drive alone.

To ensure optimal braking, disc brakes were fitted on all four wheels (while standard versions only had drum brakes on the rear wheels). To improve road holding, an anti-roll bar was added to the front axle, and the trailing arm rear axle was specifically designed for the 1000 Pistes to accommodate the rear axle of the driveshaft.

Driving the Visa 1000 Pistes on any paved road, even for short trips, clearly demonstrates that it was designed solely for off-road driving—or, more accurately, for racing. Most who have tried to use it for anything else arrived at their destination not only exhausted but also deaf. Cabin soundproofing is minimal, making conversation nearly impossible above 50 km/h without shouting or using a megaphone. The engine can be temperamental and even unbearable on the open road, often backfiring and giving the impression of being choked until reaching 4,000 rpm.

Intended for amateur drivers who lacked the means to afford such a racing machine, the Visa 1000 Pistes was priced at a hefty 120,000 francs in 1983, making it even more expensive than the Renault 5 Turbo 2. Consequently, most Citroën buyers inclined toward a sporty model opted for the GT—less spectacular in appearance and performance but much more affordable and easier to live with.

As for the “real” drivers who took the wheel of the 20 examples of the Evolution series, designed solely for Group B competition, their racing careers were rather short. They competed in several iconic rally events, including those in Kenya, Finland, and Provence in 1984, as well as the Chamonix Ice Rally in 1985. However, the Evolutions never achieved better than 2nd place in the Group B category and 8th overall at the 1985 Monte Carlo Rally.

To somewhat appease Visa die-hards who were unable to purchase a 1000 Pistes 4 x 4, Citroën introduced the limited production front-wheel-drive Visa 14 S Tonic in early 1984—an even sportier version of the Visa GT. It featured an all-white appearance similar to the Visa Chrono, with only 2,000 Tonics made.

Citroën had planned from the outset to build only the 200 Visa 1000 Pistes 4 x 4 models required for homologation. Most owners likely didn’t hesitate to “advertise” its “bad temper.” However, the Visa era in the WRC was quickly sidelined by PSA Group management in favor of the even more radical and far more powerful Citroën ZX, which earned a much more impressive racing record.

While the Visa 1000 Pistes 4 x 4 remains significantly less sought after than its Peugeot “cousin” in the collector car market, and despite its unimpressive racing record, it is still the most valuable of all Visa versions due to its rarity and the unique technical feature of its four-wheel drive.